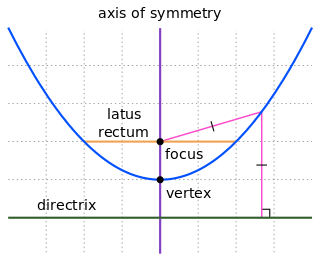

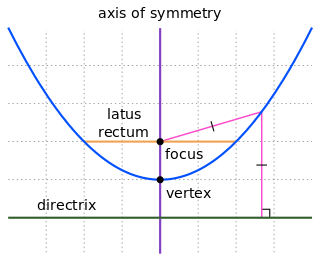

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called vertices, are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called edges, are one-dimensional line segments. The triangle's interior is a two-dimensional region. Sometimes an arbitrary edge is chosen to be the base, in which case the opposite vertex is called the apex.

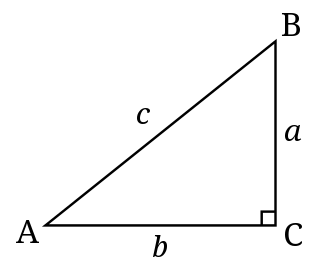

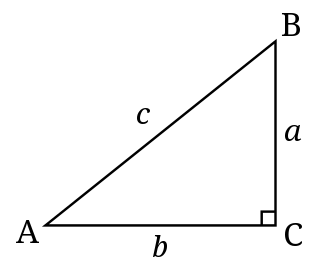

A right triangle or right-angled triangle, sometimes called an orthogonal triangle or rectangular triangle, is a triangle in which two sides are perpendicular, forming a right angle.

In geometry, a hexagon is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

In geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if their intersection forms right angles at the point of intersection called a foot. The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the perpendicular symbol, ⟂. Perpendicular intersections can happen between two lines, between a line and a plane, and between two planes.

In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts. Usually it involves a bisecting line, also called a bisector. The most often considered types of bisectors are the segment bisector, a line that passes through the midpoint of a given segment, and the angle bisector, a line that passes through the apex of an angle . In three-dimensional space, bisection is usually done by a bisecting plane, also called the bisector.

In geometry, an altitude of a triangle is a line segment through a vertex and perpendicular to a line containing the side opposite the vertex. This line containing the opposite side is called the extended base of the altitude. The intersection of the extended base and the altitude is called the foot of the altitude. The length of the altitude, often simply called "the altitude", is the distance between the extended base and the vertex. The process of drawing the altitude from the vertex to the foot is known as dropping the altitude at that vertex. It is a special case of orthogonal projection.

In geometry, an equilateral triangle is a triangle in which all three sides have the same length. In the familiar Euclidean geometry, an equilateral triangle is also equiangular; that is, all three internal angles are also congruent to each other and are each 60°. It is also a regular polygon, so it is also referred to as a regular triangle.

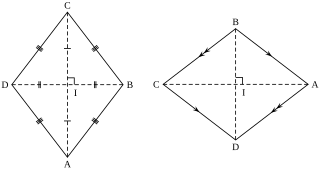

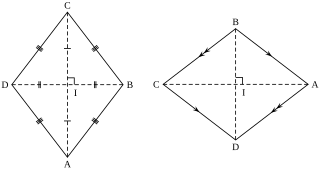

In plane Euclidean geometry, a rhombus is a quadrilateral whose four sides all have the same length. Another name is equilateral quadrilateral, since equilateral means that all of its sides are equal in length. The rhombus is often called a "diamond", after the diamonds suit in playing cards which resembles the projection of an octahedral diamond, or a lozenge, though the former sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 60° angle, and the latter sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 45° angle.

In Euclidean geometry, a cyclic quadrilateral or inscribed quadrilateral is a quadrilateral whose vertices all lie on a single circle. This circle is called the circumcircle or circumscribed circle, and the vertices are said to be concyclic. The center of the circle and its radius are called the circumcenter and the circumradius respectively. Other names for these quadrilaterals are concyclic quadrilateral and chordal quadrilateral, the latter since the sides of the quadrilateral are chords of the circumcircle. Usually the quadrilateral is assumed to be convex, but there are also crossed cyclic quadrilaterals. The formulas and properties given below are valid in the convex case.

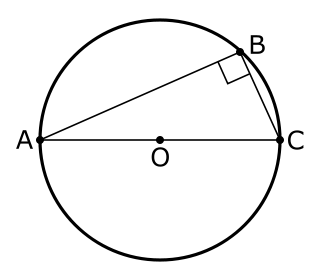

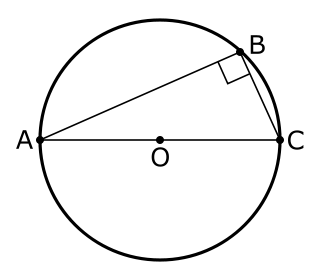

In geometry, Thales's theorem states that if A, B, and C are distinct points on a circle where the line AC is a diameter, the angle ∠ ABC is a right angle. Thales's theorem is a special case of the inscribed angle theorem and is mentioned and proved as part of the 31st proposition in the third book of Euclid's Elements. It is generally attributed to Thales of Miletus, but it is sometimes attributed to Pythagoras.

In geometry, symmedians are three particular lines associated with every triangle. They are constructed by taking a median of the triangle, and reflecting the line over the corresponding angle bisector. The angle formed by the symmedian and the angle bisector has the same measure as the angle between the median and the angle bisector, but it is on the other side of the angle bisector.

In geometry, a decagon is a ten-sided polygon or 10-gon. The total sum of the interior angles of a simple decagon is 1440°.

In geometry, a set of points are said to be concyclic if they lie on a common circle. A polygon whose vertices are concyclic is called a cyclic polygon, and the circle is called its circumscribing circle or circumcircle. All concyclic points are equidistant from the center of the circle.

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four sides of equal length and four equal angles. It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length adjacent sides. It is the only regular polygon whose internal angle, central angle, and external angle are all equal (90°), and whose diagonals are all equal in length. A square with vertices ABCD would be denoted ABCD.

In geometry, the circumscribed circle or circumcircle of a triangle is a circle that passes through all three vertices. The center of this circle is called the circumcenter of the triangle, and its radius is called the circumradius. The circumcenter is the point of intersection between the three perpendicular bisectors of the triangle's sides, and is a triangle center.

In Euclidean geometry, the Fermat point of a triangle, also called the Torricelli point or Fermat–Torricelli point, is a point such that the sum of the three distances from each of the three vertices of the triangle to the point is the smallest possible or, equivalently, the geometric median of the three vertices. It is so named because this problem was first raised by Fermat in a private letter to Evangelista Torricelli, who solved it.

In geometry, given a triangle ABC and a point P on its circumcircle, the three closest points to P on lines AB, AC, and BC are collinear. The line through these points is the Simson line of P, named for Robert Simson. The concept was first published, however, by William Wallace in 1799, and is sometimes called the Wallace line.

In Euclidean geometry, the isodynamic points of a triangle are points associated with the triangle, with the properties that an inversion centered at one of these points transforms the given triangle into an equilateral triangle, and that the distances from the isodynamic point to the triangle vertices are inversely proportional to the opposite side lengths of the triangle. Triangles that are similar to each other have isodynamic points in corresponding locations in the plane, so the isodynamic points are triangle centers, and unlike other triangle centers the isodynamic points are also invariant under Möbius transformations. A triangle that is itself equilateral has a unique isodynamic point, at its centroid(as well as its orthocenter, its incenter, and its circumcenter, which are concurrent); every non-equilateral triangle has two isodynamic points. Isodynamic points were first studied and named by Joseph Neuberg.

In Euclidean geometry, an ex-tangential quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral where the extensions of all four sides are tangent to a circle outside the quadrilateral. It has also been called an exscriptible quadrilateral. The circle is called its excircle, its radius the exradius and its center the excenter. The excenter lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect. The ex-tangential quadrilateral is closely related to the tangential quadrilateral.

![Two lines

l

1

{\displaystyle l_{1}}

and

l

2

{\displaystyle l_{2}}

are antiparallel with respect to the sides of an angle if they make the same angle

[?]

A

P

C

{\displaystyle \angle APC}

in the opposite senses with the bisector of that angle. Anti2.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Anti2.svg/220px-Anti2.svg.png)

![Given two lines

m

1

{\displaystyle m_{1}}

and

m

2

{\displaystyle m_{2}}

, lines

l

1

{\displaystyle l_{1}}

and

l

2

{\displaystyle l_{2}}

are antiparallel with respect to

m

1

{\displaystyle m_{1}}

and

m

2

{\displaystyle m_{2}}

if

[?]

1

=

[?]

2

{\displaystyle \angle 1=\angle 2}

. Anti1.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Anti1.svg/220px-Anti1.svg.png)