Related Research Articles

Evangelista Torricelli was an Italian physicist and mathematician, and a student of Galileo. He is best known for his invention of the barometer, but is also known for his advances in optics and work on the method of indivisibles. The torr is named after him.

Bonaventura Francesco Cavalieri was an Italian mathematician and a Jesuate. He is known for his work on the problems of optics and motion, work on indivisibles, the precursors of infinitesimal calculus, and the introduction of logarithms to Italy. Cavalieri's principle in geometry partially anticipated integral calculus.

Francesco Fontana was an Italian lawyer and an astronomer.

Benedetto Castelli, born Antonio Castelli, was an Italian mathematician. Benedetto was his name in religion on entering the Benedictine Order in 1595.

Vincenzo Viviani was an Italian mathematician and scientist. He was a pupil of Torricelli and Galileo.

Sister Maria Celeste was an Italian nun. She was the daughter of the scientist Galileo Galilei and Marina Gamba.

Fortunio Liceti, was an Italian physician and philosopher.

Giovanni Antonio Magini was an Italian astronomer, astrologer, cartographer, and mathematician.

Antonio Vallisneri, also rendered as Antonio Vallisnieri, was an Italian medical scientist, physician and naturalist.

Dialogo de Cecco di Ronchitti da Bruzene in perpuosito de la stella Nuova is the title of an early 17th-century pseudonymous pamphlet ridiculing the views of an aspiring Aristotelian philosopher, Antonio Lorenzini da Montepulciano, on the nature and properties of Kepler's Supernova, which had appeared in October 1604. The pseudonymous Dialogue was written in the coarse language of a rustic Paduan dialect, and first published in about March, 1605, in Padua. A second edition was published later the same year in Verona. Antonio Favaro republished the contents of the pamphlet in its original language in 1881, with annotations and a commentary in Italian. He republished it again in Volume 2 of the National Edition of Galileo's works in 1891, along with a translation into standard Italian. An English translation was published by Stillman Drake in 1976.

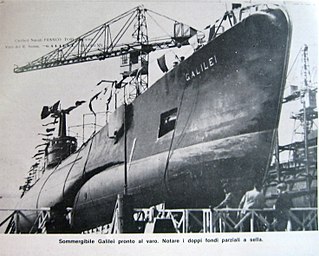

Galileo Galilei was one of four Archimede-class submarines built for the Regia Marina during the early 1930s. She was named after Galileo Galilei, an Italian astronomer and engineer.

The National Central Library of Florence is a public national library in Florence, the largest in Italy and one of the most important in Europe, one of the two central libraries of Italy, along with the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma.

Gasparo Berti was an Italian mathematician, astronomer and physicist. He was probably born in Mantua and spent most of his life in Rome. He is most famous today for his experiment in which he unknowingly created the first working barometer. Though he was best known for his work in mathematics and physics, little of his work in either survives.

Villa il Gioiello is a villa in Florence, central Italy, famous for being one of the residences of Galileo Galilei, which he lived in from 1631 until his death in 1642. It is also known as Villa Galileo.

Ostilio Ricci da Fermo (1540–1603) was an Italian mathematician.

Michelangelo Ricci (1619–1682) was an Italian mathematician and a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

Paolo Galluzzi is an Italian historian of science.

Francesco Eschinardi, also known under the pseudonym of Costanzo Amichevoli, was an Italian Jesuit, physicist and mathematician.

References

- ↑ Milighetti, Maria Chiara (2004). "Da Antonio Nardi (1598-1649 ca.) a Francesco Redi (1626-1697): L'eredità culturale di un Galileiano". Annali Aretini (in Italian). 12: 224.

- ↑ Favaro, Antonio, ed. (1890–1909). Opere di Galileo Galilei. Edizione Nazionale. Vol. XVIII (in Italian). Florence: Barbera. p. 359.

- ↑ Favaro, Antonio, ed. (1890–1909). Opere di Galileo Galilei. Edizione Nazionale. Vol. XVIII (in Italian). Florence: Barbera. pp. 342–344.

- ↑ Vassura, Giuseppe, ed. (1919). Opere di Evangelista Torricelli. Vol. III (in Italian). Faenza: Stab. tipo-lit. G. Montanari. pp. 413–416.

- ↑ Nardi, Antonio. Scene. Bound manuscript. Gal. Ms. 130 (in Italian). Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. p. 697r.

- ↑ Nardi, Antonio. Scene. Bound manuscript. Gal. Ms. 130 (in Italian). Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. p. 370v.

- ↑ Vassura, Giuseppe, ed. (1919). Opere di Evangelista Torricelli. Vol. III (in Italian). Faenza: Stab. tipo-lit. G. Montanari. pp. 249–251.

- ↑ Milighetti, Maria Chiara (2004). "Da Antonio Nardi (1598-1649 ca.) a Francesco Redi (1626-1697): L'eredità culturale di un Galileiano". Annali Aretini (in Italian). 12: 237.