Related Research Articles

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule. He inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā, first applied to him in South Africa in 1914, is now used throughout the world.

The South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result of the Second Boer War.

The Transvaal Colony was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The borders of the Transvaal Colony were larger than the defeated South African Republic. In 1910 the entire territory became the Transvaal Province of the Union of South Africa.

Johannesburg is a large city in Gauteng Province of South Africa. It was established as a small village controlled by a Health Committee in 1886 with the discovery of an outcrop of a gold reef on the farm Langlaagte. The population of the city grew rapidly, becoming a municipality in 1898. In 1928 it became a city making Johannesburg the largest city in South Africa. In 2002 it joined ten other municipalities to form the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. Today, it is a centre for learning and entertainment for all of South Africa. It is also the capital city of Gauteng.

The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, was a law, applied during the British India period. It was a legislative council act passed by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi on 18 March 1919, indefinitely extending the emergency measures of preventive indefinite detention, imprisonment without trial and judicial review enacted in the Defence of India Act 1915 during the First World War. It was enacted in the light of a perceived threat from revolutionary nationalists of re-engaging in similar conspiracies as had occurred during the war which the Government felt the lapse of the Defence of India Act would enable.

Chinese South Africans are Overseas Chinese who reside in South Africa, including those whose ancestors came to South Africa in the early 20th century until Chinese immigration was banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904. Chinese industrialists from the Republic of China (Taiwan) who arrived in the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s, and post-apartheid immigrants to South Africa now outnumber locally-born Chinese South Africans.

The following lists events that happened during 1907 in South Africa.

The Story of My Experiments with Truth is the autobiography of Mahatma Gandhi, covering his life from early childhood through to 1921. It was written in weekly installments and published in his journal Navjivan from 1925 to 1929. Its English translation also appeared in installments in his other journal Young India. It was initiated at the insistence of Swami Anand and other close co-workers of Gandhi, who encouraged him to explain the background of his public campaigns. In 1998, the book was designated as one of the "100 Best Spiritual Books of the 20th Century" by a committee of global spiritual and religious authorities.

Jan Christiaan Smuts, OM was a prominent South African and Commonwealth statesman and military leader. He served as a Boer General duning the Boer War, a British General during the First World War and was appointed Field Marshal during the Second World War. In addition to various Cabinet appointments, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 to 1924 and from 1939 to 1948. He played a leading part in the post war settlements at the end of both world wars, making significant contributions towards the creation of both the League of Nations and the United Nations.

Thillaiyadi Valliammai was a South African Tamil girl who worked with Mahatma Gandhi in her early years when she developed her nonviolent methods in South Africa fighting its apartheid regime.

Govindasamy Krishnasamy Thambi Naidoo was a South African civil rights activist. He was an early collaborator of Mahatma Gandhi leading many protests in then South Africa against racial discrimination targeted at the Indian community.

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three other colonies to form the Union of South Africa, as one of its provinces. It is now the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa.

The Indian Opinion was a newspaper established by Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi. The publication was an important tool for the political movement led by Gandhi and the Natal Indian Congress to fight racial discrimination and again civil rights for the Indian community and the native Africans in South Africa. Starting in 1903, it continued its publication until 1961.

The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) was an umbrella body founded in 1921 to coordinate between political organisations representing Indians in the various provinces of South Africa. Its members were the Natal Indian Congress (NIC), the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC), and, initially, the Cape British Indian Council. It advocated non-violent resistance to discriminatory laws and in its formative years was strongly influenced by the NIC's founder, Mahatma Gandhi.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Cape Colony was annexed by the British and officially became their colony in 1815. Britain encouraged settlers to the Cape, and in particular, sponsored the 1820 Settlers to farm in the disputed area between the colony and the Xhosa in what is now the Eastern Cape. The changing image of the Cape from Dutch to British excluded the Dutch farmers in the area, the Boers who in the 1820s started their Great Trek to the northern areas of modern South Africa. This period also marked the rise in power of the Zulu under their king Shaka Zulu. Subsequently, several conflicts arose between the British, Boers and Zulus, which led to the Zulu defeat and the ultimate Boer defeat in the Second Anglo-Boer War. However, the Treaty of Vereeniging established the framework of South African limited independence as the Union of South Africa.

Sir Henry Binns, KCMG was Prime Minister of the Colony of Natal from 5 October 1897 – 8 June 1899.

Sonja Schlesin was a South African best known for her work with Mohandas Gandhi while he was living in South Africa. She began her service as his secretary at the age of 17. By her early twenties, she had become entrusted with the executive decision making within Gandhi's law practice and sociopolitical movements. Gandhi said "during the Satyagraha days ... she led the movement single handed". She was a lifelong friend to Gandhi and would have been a fellow lawyer if she had not been female. She ended her career as a teacher of Latin and made a late attempt to become a lawyer at the age of 65.

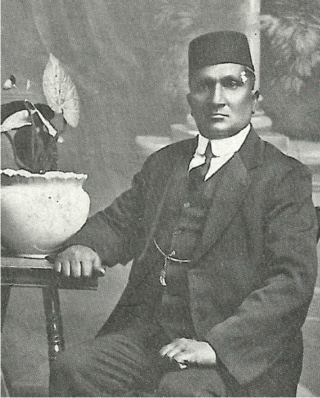

Rustomjee Jivanji Ghorkhodu, commonly known as Parsee Rustomjee, and by various orthographic variations including Parsi Rustomji and affectionately referred to as Kakaji, was an Indian-South African philanthropist and businessman, well known for his close mentorship, guidance and financial sponsorship of Mahatma Gandhi during his time in South Africa from 1893 to 1914.

The National Convention, also known as the Convention on the Closer Union of South Africa or the Closer Union Convention, was a constitutional convention held between 1908 and 1909 in Durban, Cape Town and Bloemfontein. The convention led to the adoption of the South Africa Act by the British Parliament and thus to the creation of the Union of South Africa. The four colonies of the area that would become South Africa - the Cape Colony, Natal Colony, the Orange River Colony and the Transvaal Colony - were represented at the convention, along with a delegation from Rhodesia. There were 33 delegates in total, with the Cape being represented by 12, the Transvaal eight, the Orange River five, Natal five, and Rhodesia three. The convention was held behind closed doors, in the fear that a public affair would lead delegates to refuse compromising on contentious areas of disagreement. All the delegates were white men, a third of them were farmers, ten were lawyers, and some were academics. Two-thirds had fought on either side of the Second Boer War.

The Chinese Association of Gauteng is a South African organisation that advocates for the interests of Chinese South Africans. The organisation was formed in 1903 as the Transvaal Chinese Association (TCA) in the Transvaal Colony when approximately 900 Chinese people lived in the colony.

References

- 1 2 3 Millin, Sarah Gertrude (1936). General Smuts. Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Indian Affairs". Times of London. No. 38191. 30 November 1906. p. 4 – via GALE CS67433342.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bhana, Surendra; Pachai, Bridglal (1984). A Documentary history of Indian South Africans. Internet Archive. Cape Town : D. Philip ; Stanford, Calif. : Hoover Institution Press. pp. 115–121. ISBN 978-0-8179-8102-0.

- ↑ "Court Circular". Times of London. No. 38168. London, England. 3 November 1906. p. 8 – via GALE CS134411107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Deputations To Ministers". Times of London. No. 38173. London, England. 9 November 1906. p. 4 – via GALE CS67695465.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gandhi, M.K.; Ally, H.O. (3 December 1906). "Letter: British Indians in the Transvaal". Times of London. No. 38193. London, England. p. 12 – via GALE CS201913219.

- ↑ "Deputations To Ministers". Times of London. No. 38185. London, England. 23 November 1906. p. 11 – via GALE CS185135991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "British Indians in the Transvaal". Times of London. No. 38257. London, England. 15 February 1907. p. 15 – via GALE CS251982927.

- ↑ "British Indians in South Africa". Times of London. No. 38191. London, England. 30 November 1906. p. 11 – via GALE CS185922430.

- Gandhi, M. Satyagraha in South Africa, Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad. Translated from the original Gujarati by Valji Govindji Desai