The Treaty of Trianon often referred to as the Peace Dictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon in Hungary, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed on the one side by Hungary and, on the other, by the Allied and Associated Powers, in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It formally terminated the state of war issued from World War I between most of the Allies of World War I and the Kingdom of Hungary. The treaty is mostly famous due to the territorial changes induced on Hungary and recognizing its new international borders after the First World War.

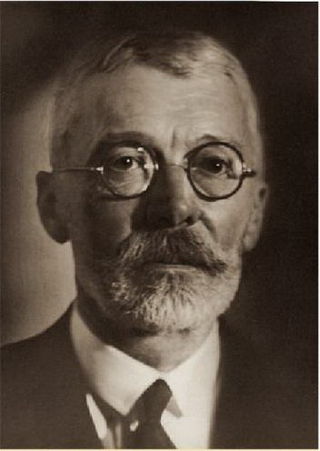

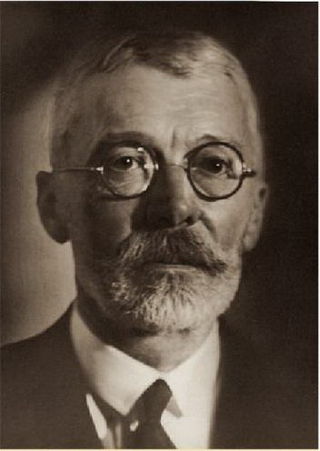

Count Mihály Ádám György Miklós Károlyi de Nagykároly was a Hungarian politician who served as a leader of the short-lived and unrecognized First Hungarian Republic from 1918 to 1919. He served as prime minister between 1 and 16 November 1918 and as president between 16 November 1918 and 21 March 1919.

Gyula Count Károlyi de Nagykároly in English: Julius Károlyi was a conservative Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1931 to 1932. He had previously been prime minister of the counter-revolutionary government in Szeged for several months in 1919. As prime minister, he generally tried to continue the moderate conservative policies of his predecessor, István Bethlen, although with less success.

István Friedrich was a Hungarian politician, footballer and factory owner who served as prime minister of Hungary for three months between August and November in 1919. His tenure coincided with a period of political instability in Hungary immediately after World War I, during which several successive governments ruled the country.

Count János Hadik de Futak was a Hungarian landowner and politician who served for 17 hours as Prime Minister of Hungary, beginning on 30 October 1918. His tenure coincided with a period of political instability in Hungary immediately after World War I, during which several successive governments ruled the country. He was forced to resign at the outbreak of the Aster Revolution on 31 October 1918, serving the shortest tenure of any Hungarian Prime Minister.

The First Hungarian Republic, until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic, was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military policy of the doctrinaire pacifist Károlyi government. It existed from 16 November 1918 until 8 August 1919, apart from a 133-day interruption in the form of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The republic was established in the wake of the dissolution of Austria-Hungary following World War I as a replacement for the Kingdom of Hungary. During the rule of Count Mihály Károlyi's pacifist cabinet, Hungary lost control over approximately 75% of its former pre-World War I territories, which was about 325,411 km2 (125,642 sq mi), without armed resistance and was subjected to unhindered foreign occupation. It was in turn succeeded by the Hungarian Soviet Republic but re-established following its demise, and ultimately replaced by the Hungarian Republic.

The union of Transylvania with Romania was declared on 1 December [O.S. 18 November] 1918 by the assembly of the delegates of ethnic Romanians held in Alba Iulia. The Great Union Day, celebrated on 1 December, is a national holiday in Romania that celebrates this event. The holiday was established after the Romanian Revolution, and celebrates the unification not only of Transylvania, but also of Bessarabia and Bukovina and parts of Banat, Crișana and Maramureș with the Romanian Kingdom. Bessarabia and Bukovina had joined with the Kingdom of Romania earlier in 1918.

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Hungary was part of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Although there are no significant battles specifically connected to Hungarian regiments, the troops suffered high losses throughout the war as the Empire suffered defeat after defeat. The result was the breakup of the Empire and eventually, Hungary suffered severe territorial losses by the closing Trianon Peace Treaty.

The Hungarian–Romanian War was fought between Hungary and Romania from 13 November 1918 to 3 August 1919. The conflict had a complex background, with often contradictory motivations for the parties involved.

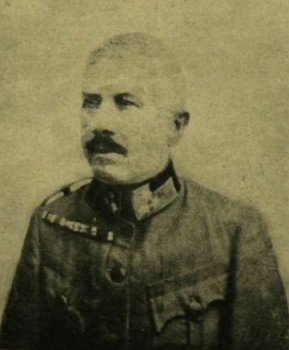

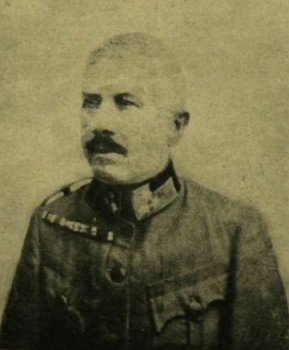

Béla Linder, Hungarian colonel of artillery, Secretary of War of Mihály Károlyi government, minister without portfolio of Dénes Berinkey government, military attaché of Hungarian Soviet Republic based in Vienna, finally the mayor of Pécs during the period of Serb occupation.

István Rakovszky de Nagyrákó et Nagyselmecz was a legitimist Hungarian politician. During the Second Royal coup d'état, Charles IV returned to Hungary to retake his throne. The attempt was unsuccessful. The king formed a rival government in Sopron and appointed Rakovszky as Prime Minister.

Records of prime ministers of Hungary from 1848 to the present.

The Hungarian National Council was an institution from the time of transition from the Kingdom of Hungary to the People's Republic in 1918. At the congress of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party (MSZDP) in October 1918 called for the Socialist Left József Pogány minority to its own policy, which should be based on the emerging workers 'and soldiers' councils. In contrast prevailed Zsigmond Kunfi in the MSZDP that the liberal left "48" party of Count Mihály Károlyi and the bourgeois radical party of Oszkár Jászi was entered into an alliance. These three parties formed on 25 October, the Hungarian National Council.

Lajos Návay de Földeák was a Hungarian jurist and politician, who served as Speaker of the House of Representatives between 1911 and 1912.

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary was a short-lived communist state that existed from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919, succeeding the First Hungarian Republic. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a small communist rump state which, at its time of establishment, controlled approximately only 23% of Hungary's historic territory. The head of government was Sándor Garbai, but the influence of the foreign minister Béla Kun of the Party of Communists in Hungary was much stronger. Unable to reach an agreement with the Triple Entente, which maintained an economic blockade of Hungary, in dispute with neighboring countries over territorial disputes, and beset by profound internal social changes, the Hungarian Soviet Republic failed in its objectives and was abolished a few months after its existence. Its main figure was the Communist Béla Kun, despite the fact that in the first days the majority of the new government consisted of radical Social Democrats. The new system effectively concentrated power in the governing councils, which exercised it in the name of the working class.

The National Party of Work was a liberal political party in Hungary between 1910 and the end of World War I. The party was established by István Tisza after the defeat of the Liberal Party in the 1905 and 1906 elections. The party was led by László Lukács, who served as Prime Minister from 1912 to 1913. As its predecessor the Liberal Party, the new party also remained bitterly unpopular among ethnic Hungarian voters, and could rely mostly on the support of ethnic minority voters.

The dissolution of Austria-Hungary was a major geopolitical event that occurred as a result of the growth of internal social contradictions and the separation of different parts of Austria-Hungary. The more immediate reasons for the collapse of the state were World War I, the 1918 crop failure, general starvation and the economic crisis. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had additionally been weakened over time by a widening gap between Hungarian and Austrian interests. Furthermore, a history of chronic overcommitment rooted in the 1815 Congress of Vienna in which Metternich pledged Austria to fulfill a role that necessitated unwavering Austrian strength and resulted in overextension. Upon this weakened foundation, additional stressors during World War I catalyzed the collapse of the empire. The 1917 October Revolution and the Wilsonian peace pronouncements from January 1918 onward encouraged socialism on the one hand, and nationalism on the other, or alternatively a combination of both tendencies, among all peoples of the Habsburg monarchy.

The armistice of Belgrade was an agreement on the termination of World War I hostilities between the Triple Entente and the Kingdom of Hungary concluded in Belgrade on 13 November 1918. It was largely negotiated by General Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, as the commanding officer of the Allied Army of the Orient, and Hungarian Prime Minister Mihály Károlyi, on 7 November. It was signed by General Paul Prosper Henrys and vojvoda Živojin Mišić, as representatives of the Allies, and by the former Hungarian Minister of War, Béla Linder.

The following lists events in the year 1919 in Hungary.

The following lists events in the year 1918 in Hungary.