Art Deco, short for the French Arts décoratifs, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in Paris in the 1910s, and flourished in the United States and Europe during the 1920s to early 1930s. Through styling and design of the exterior and interior of anything from large structures to small objects, including how people look, Art Deco has influenced bridges, buildings, ships, ocean liners, trains, cars, trucks, buses, furniture, and everyday objects including radios and vacuum cleaners.

Issey Miyake was a Japanese fashion designer. He was known for his technology-driven clothing designs, exhibitions and fragrances, such as L'eau d'Issey, which became his best-known product.

Googie architecture is a type of futurist architecture influenced by car culture, jets, the Atomic Age and the Space Age. It originated in Southern California from the Streamline Moderne architecture of the 1930s, and was popular in the United States from roughly 1945 to the early 1970s.

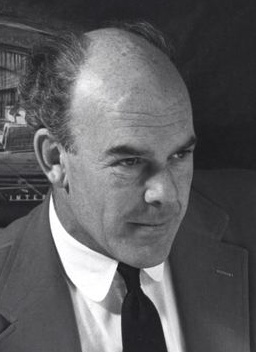

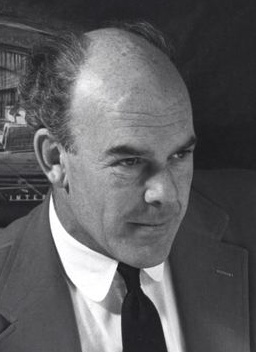

Pierre Cardin, born Pietro Costante Cardin, was an Italian-born naturalised-French fashion designer. He is known for what were his avant-garde style and Space Age designs. He preferred geometric shapes and motifs, often ignoring the female form. He advanced into unisex fashions, sometimes experimental, and not always practical. He founded his fashion house in 1950 and introduced the "bubble dress" in 1954.

Eero Aarnio is a Finnish designer, noted for his innovative furniture designs in the 1960s, such as his plastic and fibreglass chairs. He was born in Helsinki.

John Edward Lautner was an American architect. Following an apprenticeship in the mid-1930s with the Taliesin Fellowship led by Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner opened his own practice in 1938, where he worked for the remainder of his career. Lautner practiced primarily in California, and the majority of his works were residential. Lautner is perhaps best remembered for his contribution to the development of the Googie style, as well as for several Atomic Age houses he designed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which include the Leonard Malin House, Paul Sheats House, and Russ Garcia House.

In architecture and decorative art, ornament is decoration used to embellish parts of a building or object. Large figurative elements such as monumental sculpture and their equivalents in decorative art are excluded from the term; most ornaments do not include human figures, and if present they are small compared to the overall scale. Architectural ornament can be carved from stone, wood or precious metals, formed with plaster or clay, or painted or impressed onto a surface as applied ornament; in other applied arts the main material of the object, or a different one such as paint or vitreous enamel may be used.

Mid-century modern (MCM) is a movement in interior design, product design, graphic design, architecture and urban development that was present in all the world, but more popular in the United States, Mexico, Brazil and Europe from roughly 1945 to 1970 during the United States's post-World War II period.

Florence Marguerite Knoll Bassett was an American architect, interior designer, furniture designer, and entrepreneur who has been credited with revolutionizing office design and bringing modernist design to office interiors. Knoll and her husband, Hans Knoll, built Knoll Associates into a leader in the fields of furniture and interior design. She worked to professionalize the field of interior design, fighting against gendered stereotypes of the decorator. She is known for her open office designs, populated with modernist furniture and organized rationally for the needs of office workers. Her modernist aesthetic was known for clean lines and clear geometries that were humanized with textures, organic shapes, and colour.

Artek is a Finnish furniture company. It was founded in December 1935 by architect Alvar Aalto and his wife Aino Aalto, visual arts promoter Maire Gullichsen and art historian Nils-Gustav Hahl. The founders chose a non-Finnish name: the neologism Artek was meant to manifest the desire to combine art and technology. This echoed a main idea of the International Style movement, especially the Bauhaus, to emphasize the technical expertise in production and quality of materials, instead of historical-based, eclectic or frivolous ornamentation.

Shiro Kuramata is one of Japan's most important designers of the 20th century.

The bubble chair was designed by Finnish furniture designer Eero Aarnio in 1968. It is based on his Ball Chair. The main difference is that the Bubble Chair is attached to the ceiling with a chain, while being made of transparent material which lets the light inside from all directions. The acrylic is heated and blown into a round shape like a soap bubble, within a solid steel frame. It is considered an industrial design classic and to have advanced the usage of plastics in furniture design. The chair is considered modernist or Space Age in design and is often used to symbolize the 1960s period.

Shirin Guild is an Iranian-born British fashion designer. Her fashion label was established in London, in 1991. Her clothing design is minimalist and she has reworked Iranian clothing traditions through a "reductionist aesthetic". Her design work has been described as "trans-cultural".

Ikko Tanaka was a Japanese graphic designer.

Ideas from mathematics have been used as inspiration for fiber arts including quilt making, knitting, cross-stitch, crochet, embroidery and weaving. A wide range of mathematical concepts have been used as inspiration including topology, graph theory, number theory and algebra. Some techniques such as counted-thread embroidery are naturally geometrical; other kinds of textile provide a ready means for the colorful physical expression of mathematical concepts.

Antti Aarre Nurmesniemi was a Finnish designer. He is perhaps best known for his coffee pots and his interior design work.

Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology was an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that showcased the dichotomy between Manus, also known as haute couture, and Machina, also known as prêt-à-porter. The Metropolitan Museum of Art debuted this exhibition during the 2016 Met Gala and ran it from May 5, 2016 to September 5, 2016. It included over 120 pieces from designers like Chanel and Christian Dior, varying from the 20th Century to present day.

Satoshi Kondo is the artistic. director and head designer for Japanese fashion brand Issey Miyake.

Kosuke Tsumura is a Japanese fashion designer and artist particularly known for his Final Home label.