Edward Cornwallis was a British career military officer and member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family, who reached the rank of Lieutenant General. After Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, he was appointed Groom of the Chamber for King George II. He was then made Governor of Nova Scotia (1749–1752), one of the colonies in North America, and assigned to establish the new town of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Later Cornwallis returned to London, where he was elected as MP for Westminster and married the niece of Robert Walpole, Great Britain's first Prime Minister. Cornwallis was next appointed as Governor of Gibraltar.

Fort Gaspareaux was a French fort at the head of Baie Verte near the mouth of the Gaspareaux River and just southeast of the modern community of Strait Shores, New Brunswick, Canada, on the Isthmus of Chignecto. It was built during Father Le Loutre's War and is now a National Historic Site of Canada overlooking the Northumberland Strait.

West Lawrencetown is a residential community within the Halifax Regional Municipality Nova Scotia on the Eastern Shore on Route 207 along the scenic route Marine Drive.

Dartmouth founded in 1750, is a Metropolitan Area and former city in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

Lawrencetown is a Canadian rural community in the Halifax Regional Municipality in Nova Scotia, Canada. The settlement was established during the eve of Father Le Loutre's War and at the beginning of the French and Indian War.

The Battle at St. Croix was fought during Father Le Loutre's War between Gorham's Rangers and Mi'kmaq at Battle Hill in the community of St. Croix, Nova Scotia. The battle lasted from March 20–23, 1750.

The Raid on Dartmouth occurred during Father Le Loutre's War on May 13, 1751, when a Mi'kmaq and Acadian militia from Chignecto, under the command of Acadian Joseph Broussard, raided Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, destroying the town and killing twenty British villagers and wounding British regulars. The town was protected by a blockhouse on Blockhouse Hill with William Clapham's Rangers and British regulars from the 45th Regiment of Foot. This raid was one of seven Miꞌkmaq and Acadians would conduct against the town during the war.

The siege of Grand Pré happened during Father Le Loutre's War and was fought between the British and the Wabanaki Confederacy and Acadian militia. The siege happened at Fort Vieux Logis, Grand-Pré. The native and Acadia militia laid siege to Fort Vieux Logis for a week in November 1749. One historian states that the intent of the siege was to help facilitate the Acadian Exodus from the region.

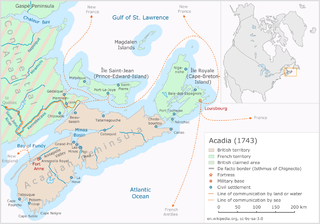

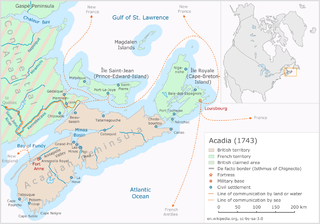

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia.c On one side of the conflict, the British and New England colonists were led by British officer Charles Lawrence and New England Ranger John Gorham. On the other side, Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadia militia in guerrilla warfare against settlers and British forces. At the outbreak of the war there were an estimated 2500 Mi'kmaq and 12,000 Acadians in the region.

The Acadian Exodus happened during Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) and involved almost half of the total Acadian population of Nova Scotia deciding to relocate to French controlled territories. The three primary destinations were: the west side of the Mesagoueche River in the Chignecto region, Isle Saint-Jean and Île-Royale. The leader of the Exodus was Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre, whom the British gave the code name "Moses". Le Loutre acted in conjunction with Governor of New France, Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, who encouraged the Acadian migration. A prominent Acadian who transported Acadians to Ile St. Jean and Ile Royal was Joseph-Nicolas Gautier. The overall upheaval of the early 1750s in Nova Scotia was unprecedented. Present-day Atlantic Canada witnessed more population movements, more fortification construction, and more troop allocations than ever before in the region. The greatest immigration of the Acadians between 1749 and 1755 took place in 1750. Primarily due to natural disasters and British raids, the Exodus proved to be unsustainable when Acadians tried to develop communities in the French territories.

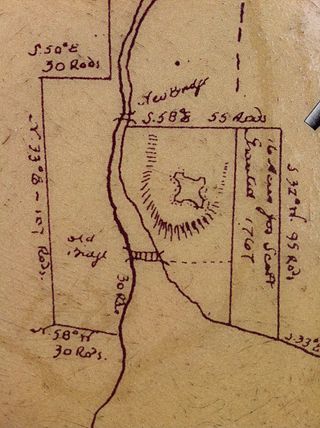

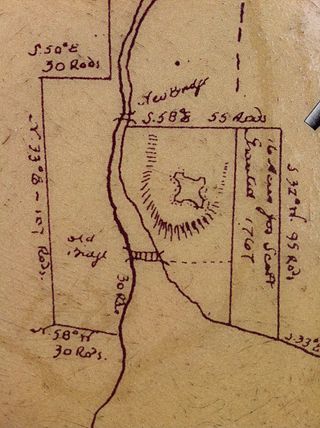

Fort Vieux Logis was a small British frontier fort built at present-day Hortonville, Nova Scotia, Canada in 1749, during Father Le Loutre's War (1749). Ranger John Gorham moved a blockhouse he erected in Annapolis Royal in 1744 to the site of Vieux Logis. The fort was in use until 1754. The British rebuilt the fort again during the French and Indian War and named it Fort Montague (1760).

Fort Menagoueche was a French fort at the mouth of the St. John River, New Brunswick, Canada. French Officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot and Ignace-Philippe Aubert de Gaspé built the fort during Father Le Loutre's War and eventually burned it themselves as the French retreated after losing the Battle of Beausejour. It was reconstructed as Fort Frederick by the British.

The Battle at Chignecto happened during Father Le Loutre's War when Charles Lawrence, in command of the 45th Regiment of Foot and the 47th Regiment, John Gorham in command of the Rangers and Captain John Rous in command of the navy, fought against the French monarchists at Chignecto. This battle was the first attempt by the British to occupy the head of the Bay of Fundy since the disastrous Battle of Grand Pré three years earlier. They fought against a militia made up of Mi'kmaq and Acadians led by Jean-Louis Le Loutre and Joseph Broussard (Beausoliel). The battle happened at Isthmus of Chignecto, Nova Scotia on 3 September 1750.

Jean Baptiste Cope was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. He maintained close ties with the Acadians along the Bay of Fundy, speaking French and being Catholic. During Father Le Loutre’s War, Cope participated in both military efforts to resist the British and also efforts to create peace with the British. During the French and Indian War he was at Miramichi, New Brunswick, where he is presumed to have died during the war. Cope is perhaps best known for signing the Treaty of 1752 with the British, which was upheld in the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 and is celebrated every year along with other treaties on Treaty Day.

The Raid on Dartmouth (1749) occurred during Father Le Loutre's War on September 30, 1749 when a Mi'kmaw militia from Chignecto raided Major Ezekiel Gilman's sawmill at present-day Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, killing four workers and wounding two. This raid was one of seven the Wabanaki Confederacy and Acadians would conduct against the settlement during the war.

Fort Sackville was a British fort in present-day Bedford, Nova Scotia. It was built during Father Le Loutre's War by British adjacent to present-day Scott Manor House, on a hill overlooking the Sackville River to help prevent French, Acadian and Mi'kmaq attacks on Halifax. The fort consisted of a blockhouse, a guard house, a barracks that housed 50 soldiers, and outbuildings, all encompassed by a palisade. Not far from the fort was a rifle range. The fort was named after George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville.

The Attack at Jeddore happened on May 19, 1753, off Jeddore, Nova Scotia, during Father Le Loutre's War. The Mi'kmaq killed nine of the British delegates and spared the life of the French-speaking translator Anthony Casteel, who wrote one of the few captivity narratives that exist from Acadia and Nova Scotia.

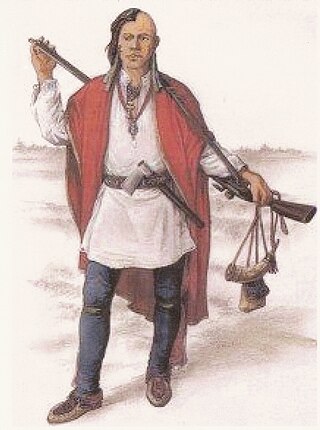

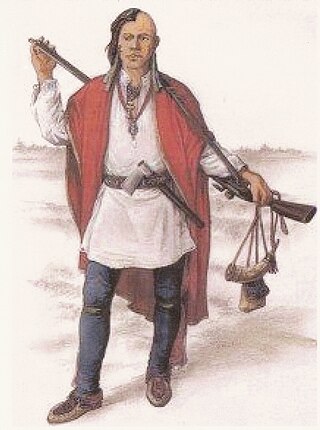

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who participated in wars against the English independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants. After some engagements against the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties. After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy and French royal forces. A number of Acadians provided military intelligence, sanctuary, and logistical support to the various resistance movements against British rule in Acadia, while other Acadians remained neutral in the contest between the Franco–Wabanaki Confederacy forces and the British. The Acadian militias managed to maintain an effective resistance movement for more than 75 years and through six wars before their eventual demise. According to Acadian historian Maurice Basque, the story of Evangeline continues to influence historic accounts of the expulsion, emphasising Acadians who remained neutral and de-emphasising those who joined resistance movements. While Acadian militias were briefly active during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century. After confederation, Acadians eventually joined the Canadian War efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Joseph Broussard and Joseph-Nicolas Gautier.

The Lunenburg campaign was executed by the Mi'kmaq militia and Acadian militia against the Foreign Protestants who the British had settled on the Lunenburg Peninsula during the French and Indian War. The British deployed Joseph Gorham and his Rangers along with Captain Rudolf Faesch and regular troops of the 60th Regiment of Foot to defend Lunenburg. The campaign was so successful, by November 1758, the members of the House of Assembly for Lunenburg stated "they received no benefit from His Majesty's Troops or Rangers" and required more protection.