The Potomac River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States that flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is 405 miles (652 km) long, with a drainage area of 14,700 square miles (38,000 km2), and is the fourth-largest river along the East Coast of the United States and the 21st-largest in the United States. Over 5 million people live within its watershed.

Paw Paw is a town in Morgan County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 410 at the 2020 census. The town is known for the nearby Paw Paw Tunnel. Paw Paw was incorporated by the Circuit Court of Morgan County on April 8, 1891, and named after pawpaw, a wild fruit that grows in abundance throughout this region. Paw Paw is the westernmost incorporated community in Morgan County, and the Hagerstown-Martinsburg, MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal and occasionally called the Grand Old Ditch, operated from 1831 until 1924 along the Potomac River between Washington, D.C., and Cumberland, Maryland. It replaced the Potomac Canal, which shut down completely in 1828, and could operate during months in which the water level was too low for the former canal. The canal's principal cargo was coal from the Allegheny Mountains.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of the National Road early in the century, wanted to do business with settlers crossing the Appalachian Mountains. The railroad faced competition from several existing and proposed enterprises, including the Albany-Schenectady Turnpike, built in 1797, the Erie Canal, which opened in 1825, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

The Potomac Company was created in 1785 to make improvements to the Potomac River and improve its navigability for commerce. The project is perhaps the first conceptual seed planted in the minds of the new American capitalists in what became a flurry of transportation infrastructure projects, most privately funded, that drove wagon road turnpikes, navigations, and canals, and then as the technology developed, investment funds for railroads across the rough country of the Appalachian Mountains. In a few decades, the eastern seaboard was crisscrossed by private turnpikes and canals were being built from Massachusetts to Illinois ushering in the brief seven decades of the American Canal Age. The Potomac Company's achievement was not just to be an early example, but of being significant also in size and scope of the project, which involved taming a mountain stream fed river with icing conditions and unpredictable freshets (floods).

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park is located in the District of Columbia and the state of Maryland. The park was established in 1961 as a National Monument by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to preserve the neglected remains of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and many of its original structures.

The Potomac Heritage Trail, also known as the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail or the PHT, is a designated National Scenic Trail corridor spanning parts of the mid-Atlantic region of the United States that will connect various trails and historic sites in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia. The trail network includes 710 miles (1,140 km) of existing and planned sections, tracing the natural, historical, and cultural features of the Potomac River corridor, the upper Ohio River watershed in Pennsylvania and western Maryland, and a portion of the Rappahannock River watershed in Virginia. The trail is managed by the National Park Service and is one of three National Trails that are official NPS units.

The Patowmack Canal, sometimes called the Potomac Canal, is a series of five inoperative canals located in Maryland and Virginia, United States, that was designed to bypass rapids in the Potomac River upstream of the present Washington, D.C., area. The most well known of them is the Great Falls skirting canal, whose remains are managed by the National Park Service since it is within Great Falls Park, an integral part of the George Washington Memorial Parkway.

The James River and Kanawha Canal was a partially built canal in Virginia intended to facilitate shipments of passengers and freight by water between the western counties of Virginia and the coast. Ultimately its towpath became the roadbed for a rail line following the same course.

The Western Maryland Railway was an American Class I railroad (1852–1983) that operated in Maryland, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. It was primarily a coal hauling and freight railroad, with a small passenger train operation.

Oldtown is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Allegany County, Maryland, United States, along the North Branch Potomac River. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 86.

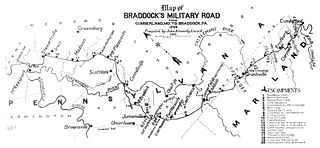

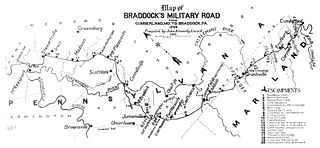

Cumberland, Maryland is named after the son of King George II, Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland. It is built on the site of the old Fort Cumberland, a launch pad for British General Edward Braddock's ill-fated attack on the stronghold of Fort Duquesne during the French and Indian War.

Canal Parkway, which carries the unsigned Maryland Route 61 designation, is a state highway and automobile parkway in the U.S. state of Maryland. The road begins at the West Virginia state line at the North Branch Potomac River opposite Wiley Ford, where the highway continues south as West Virginia Route 28. The parkway runs 1.94 miles (3.12 km) north to MD 51 within the city of Cumberland. Canal Parkway provides a connection between downtown Cumberland and the South Cumberland neighborhood and with Greater Cumberland Regional Airport, which is located in Mineral County, West Virginia.

Seneca Quarry is a historic site located at Seneca, Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on the north bank of the Potomac River, just west of Seneca Creek. The quarry was the source of stone for two Potomac River canals: the Patowmack Canal on the Virginia side of Great Falls; and the C&O Canal, having supplied red sandstone for the latter for locks 9, 11, 15 - 27, and 30, the accompanying lock houses, and Aqueduct No. 1, better known as Seneca Aqueduct, constructed from 1828 to 1833.

The Appalachian region has always had to allocate much resources and time into transportation due to the region's notable and unique geography. Mountainous terrain and commonly occurring adverse weather effects such as heavy fog and snowfall made roads hazardous and taxing on the traveling vehicles. Initially, European settlers found gaps in the mountains, among them the Cumberland Gap and the Wilderness Road. Another notable challenge of Appalachian travel is the political elements of constructing transportation routes. Most travel systems are funded by municipalities, but since The Appalachian area has several different states it can be difficult for the various governments to agree on how to work on transportation. The most influential forms of travel in the Appalachian region are based on water trading routes, roads and railroads.

Matildaville is a ghost town located along the Patowmack Canal near present day Great Falls, Virginia, United States. It was named for the wife of Light Horse Harry Lee, on 40 acres of land owned at the time by Bryan Fairfax, 8th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, and served as headquarters for the Patowmack Company from 1785 until 1799. Now, all that remains of the town are a series of ruins on the grounds of Great Falls Park.

The Canal Age is a term of art used by historians of Science, Technology, and Industry. Various parts of the world have had various canal ages; the main ones belong to civilizations, dynastic Empires of India, China, Southeast Asia, and mercantile Europe. Cultures make canals as they make other engineering works, and canals make cultures. They make industry, and until the era when steam locomotives attained high speeds and power, the canal was by far the fastest way to travel long distances quickly. Commercial canals generally had boatmen shifts that kept the barges moving behind mule teams 24 hours a day. Like many North American canals of the 1820s-1840s, the canal operating companies partnered with or founded short feeder railroads to connect to their sources or markets. Two good examples of this were funded by private enterprise:

- The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company used vertically integrated mining raw materials, transporting them, manufacturing with them, and merchandising by building coal mines, the instrumental Lehigh Canal, and feeding their own iron goods manufacturing industries and assuaging the American Republic's first energy crisis by increasing coal production from 1820 onwards using the nation's second constructed railway, the Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad.

- The second coal road and canal system was inspired by LC&N's success. The Delaware and Hudson Canal and Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad. The LC&N operation was aimed at supplying the country's premier city, Philadelphia with much needed fuel. The D&H companies were founded purposefully to supply the explosively growing city of New York's energy needs.

Swains Lock and lock house are part of the 184.5-mile (296.9 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. It is located at towpath mile-marker 16.7 near Potomac, Maryland, and within the Travilah census-designated place in Montgomery County, Maryland. The lock and lock house were built in the early 1830s and began operating shortly thereafter.

Riley's Lock (Lock 24) and lock house are part of the 184.5-mile (296.9 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. They are located at towpath mile-marker 22.7 adjacent to Seneca Creek, in Montgomery County, Maryland. The lock is sometimes identified as Seneca because of the Seneca Aqueduct that carried the canal over the creek to the lift lock. The name Riley comes from John C. Riley, who was lock keeper from 1892 until the canal closed permanently in 1924.

Violette's Lock is part of the 184.5-mile Chesapeake and Ohio Canal that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. It is located at towpath mile-marker 22.1, in Montgomery County, Maryland. The name Violette comes from Alfred L. "Ap" Violette and his wife Kate, who were lock keepers from the beginning of the 20th century through the permanent closure of the canal in 1924.