Schmalkaldic War and the Battle of Mühlberg

In June 1546, Pope Paul III entered into an agreement with Holy Roman Emperor Charles V to curb the spread of the Protestant Reformation. The agreement stated, in part:

In the name of God and with the help and assistance of his Papal Holiness, his Imperial Majesty should prepare himself for war, and equip himself with soldiers and everything pertaining to warfare against those who objected to the Council [of Trent], against the Smalcald League, and against all who were addicted to the false belief and error in Germany, and that he do so with all his power and might, in order to bring them back to the old faith and to the obedience of the Holy See. [6]

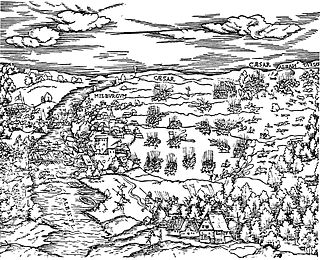

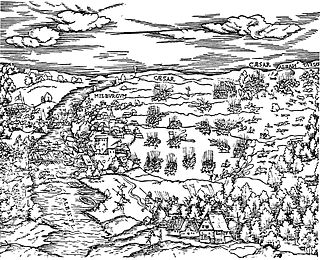

Shortly thereafter, Maurice of Saxony invaded the lands of his rival and stepbrother John Frederick, beginning the brief, but devastating, conflict known as the Schmalkaldic War. The military might of Maurice combined with that of Charles V proved to be overwhelming to John Frederick and the Protestant Schmalkaldic League. On 24 April 1547, the armies of the Schmalkaldic League were decisively defeated at the Battle of Mühlberg.

Following the defeat of the Schmalkaldic League at Mühlberg, Charles V's forces took and occupied the Lutheran territories in quick succession. On 19 May 1547 Wittenberg, the heart of the Reformation and the final resting place of Martin Luther’s remains, fell to the Emperor without a fight.

The Interim

Charles V had won a military victory but realized that his only chance he had to contain Lutheranism as a movement effectively was to pursue political and ecclesiastical compromises to restore religious peace in the Empire. The series of decrees issued by the Emperor became known as an “Interim” because they were intended to govern the church only temporarily pending the conclusions of the general council convened at Trent by Pope Paul III in December 1545.

The first draft of the twenty-six chapter decree was written by Julius von Pflug, but several theologians were involved in the final draft: on the Catholic side, Michael Helding, Eberhard Billick, Pedro Domenico Soto and Pedro de Malvenda; on the Protestant side, John Agricola. [7]

Included in the provisions of the Interim was that the Lutherans restore the number of sacraments (which the Lutherans reduced to two: Baptism, the Lord's Supper) and that the churches restore a number of specifically Roman ceremonies, doctrines, and practices that had been discarded by the Lutheran reformers, including transubstantiation, and the rejection of the doctrine of justification by grace, through faith alone. The God-given authority of the Pope over all bishops and the whole Church was reaffirmed but with the proviso that "the powers that he has should be used not to destroy but to uplift".

In stark contrast to Charles V's past attitude, significant concessions were made to the Protestants. What was basically a new code of religious practices permitted both clerical marriage and communion under both kinds. The Mass was reintroduced, but the offertory was to be seen as an act of remembrance and thanks, rather than an act of propitiation as in traditional Catholic dogma. The Interim went further in making significant statements on other matters of dogma such as justification by faith, the veneration of the saints, and the authority of the Scriptures. Even such details as the practice of fasting was breached upon. [8]

The attempt by the emperor to devise a formula to which both Catholics and Protestants of Germany could subscribe was objected to outright by the Catholic Electors, the prince-bishops and the pope even before the decree was published. Therefore, as a decree, the Interim applied only to the Protestant princes, who were given just 18 days to signify their compliance. [9]

Although Philip Melanchthon, a friend of Luther's and co-architect and voice of the Reformation movement, was willing to compromise on those issues for the sake of peace, the Augsburg Interim was rejected by a significant number of Lutheran pastors and theologians.

Pastors who refused to follow the regulations of the Augsburg Interim were removed from office and banished; some were imprisoned and some were even executed. In Swabia and along the Rhine River, some four hundred pastors went to prison, rather than agree to the Interim. They were exiled, and some of their families were killed or died as a result. Some preachers left for England (McCain et al., 476).

As a result of the Interim, many Protestant leaders, such as Martin Bucer, fled to England, where they would influence the English Reformation.

Charles V tried to enforce the Interim in the Holy Roman Empire but was successful only in territories under his military control, such as Württemberg and certain imperial cities in southern Germany. [10] There was a great deal of political opposition to the Interim. Many Catholic princes did not accept the Interim since they were worried about rising imperial authority. The papacy refused to recognize the Interim for over a year, as it was seen as an infringement upon papal jurisdiction. [11]

Leipzig Interim

In a further effort to compromise, Melanchthon strived for a second "Interim". Maurice of Saxony, who had been Charles's ally in the previous conflict, worked with Melanchthon and his supporters a compromise known as the Leipzig Interim in late 1548. Despite its even greater concessions to Protestantism, it was barely enforced. [12]

Protestant leaders rejected the terms of the Augsburg Interim. The Leipzig Interim was designed to allow Lutherans to retain their core theological beliefs, specifically where the doctrine of justification by grace was concerned, but to make them yield in other less important matters, such as church rituals. This compromise document again drew opposition. Those who supported the Leipzig Interim became identified as Philippists, as they supported Melanchthon's efforts at compromise. Those who opposed Melanchthon became known as "Gnesio-Lutherans", or "genuine" Lutherans.

Maurice, seeing that the Leipzig Interim was a political failure, began making plans to drive Charles V and his army from Saxony. It was, in his estimation, "more expedient for him [Maurice] to be viewed as a champion of Lutheranism than as a traitor" (McCain et al., 480). On 5 April 1552, Maurice attacked Charles V's forces at Augsburg, and Charles was forced to withdraw. This victory eventually resulted in the signing of the treaties of Passau (2 August 1552) and Augsburg (1555). These two treaties resulted in the principle "Cuius regio, eius religio" – He who rules, his the religion – allowing the ruler of a territory to set the religion therein.

The Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent, now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the embodiment of the Counter-Reformation.

Maximilian II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1564 until his death in 1576. A member of the Austrian House of Habsburg, he was crowned King of Bohemia in Prague on 14 May 1562 and elected King of Germany on 24 November 1562. On 8 September 1563 he was crowned King of Hungary and Croatia in the Hungarian capital Pressburg. On 25 July 1564 he succeeded his father Ferdinand I as ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Schmalkaldic League was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

The Peace of Augsburg, also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Schmalkaldic League, signed in September 1555 at the imperial city of Augsburg. It officially ended the religious struggle between the two groups and made the legal division of Christianity permanent within the Holy Roman Empire, allowing rulers to choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official confession of their state. However, the Peace of Augsburg arrangement is also credited with ending much Christian unity around Europe. Calvinism was not allowed until the Peace of Westphalia.

Cuius regio, eius religio is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective freedom of religion within Western civilization. Before tolerance of individual religious divergences became accepted, most statesmen and political theorists took it for granted that religious diversity weakened a state – and particularly weakened ecclesiastically-transmitted control and monitoring in a state. The principle of "cuius regio" was a compromise in the conflict between this paradigm of statecraft and the emerging trend toward religious pluralism developing throughout the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire. It permitted assortative migration of adherents to just two theocracies, Roman Catholic and Lutheran, eliding other confessions.

Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, nicknamed der Großmütige, was a German nobleman and champion of the Protestant Reformation, notable for being one of the most important of the early Protestant rulers in Germany.

The Battle of Mühlberg took place near Mühlberg in the Electorate of Saxony in 1547, during the Schmalkaldic War. The Catholic princes of the Holy Roman Empire led by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V decisively defeated the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League of Protestant princes under the command of Elector John Frederick I of Saxony and Landgrave Philip I of Hesse.

The Schmalkaldic War was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, commanded by the Duke of Alba and the Duke of Saxony, and the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League within the domains of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessions since the 10th century. In 1282, the diet of Augsburg assigned the control of Austria to the House of Habsburg. In the 16th century, twelve of thirty-five imperial diets were held in Augsburg, a result of the close financial relationship between the Augsburg-based banking families such as the Fugger and the reigning Habsburg emperors, particularly Maximilian I and his grandson Charles V. Nevertheless, the meetings of 1518, 1530, 1547/48 and 1555, during the Reformation and the ensuing religious war between the Catholic emperor and the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, are especially noteworthy. With the Peace of Augsburg, the cuius regio, eius religio principle let each prince decide the religion of his subjects and inhabitants who could not conform could leave.

The Peace of Passau was an attempt to resolve religious tensions in the Holy Roman Empire. After Emperor Charles V won a victory against Protestant forces in the Schmalkaldic War of 1547, he implemented the Augsburg Interim, which largely reaffirmed Roman Catholic beliefs. This angered many Protestant princes, and led by Maurice of Saxony, in January 1552 several formed an alliance with Henry II of France in the Treaty of Chambord. In return for French funding and assistance, Henry was promised lands in western Germany. In the ensuing Princes' Revolt, also known as the Second Schmalkaldic War, Charles was driven out of Germany to his ancestral lands in Austria by the Protestant alliance, while Henry captured the three Rhine Bishoprics of Metz, Verdun and Toul.

Maurice was Duke (1541–47) and later Elector (1547–53) of Saxony. His clever manipulation of alliances and disputes gained the Albertine branch of the Wettin dynasty extensive lands and the electoral dignity.

Julius von Pflug was the last Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Naumburg from 1542 until his death. He was one of the most significant reformers involved with the Protestant Reformation.

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

The Treaty of Chambord was an agreement signed on 15 January 1552 at the Château de Chambord between the Catholic King Henry II of France and three Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire led by Elector Maurice of Saxony. Based on the terms of the treaty, Maurice ceded the vicariate over the Three Bishoprics of Toul, Verdun, and Metz to France. In return, he was promised military and economic aid from Henry II in order to fight against the forces of Emperor Charles V of Habsburg.

Otto Truchsess von Waldburg was Prince-Bishop of Augsburg from 1543 until his death and a Cardinal of the Catholic Church.

The Leipzig Interim was one of several temporary settlements between the Emperor Charles V and German Lutherans following the Schmalkaldic War. It was presented to an assembly of Saxon political estates in December 1548. Though not adopted by the assembly, it was published by its critics under the name "Leipzig Interim."

Wolfgang, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, was a German prince of the House of Ascania and ruler of the principality of Anhalt-Köthen. He was one of the earliest Protestant rulers in the Holy Roman Empire.

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, Confessio Augustana, is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Reformation. The Augsburg Confession was written in both German and Latin and was presented by a number of German rulers and free-cities at the Diet of Augsburg on 25 June 1530.

An imperial election was held in Regensburg on 28 November 1562 to select the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Second Schmalkaldic War, also known as the Princes' Revolt, was an uprising of German Protestant princes led by elector Maurice of Saxony against the Catholic emperor Charles V that broke out in 1552. Historians disagree whether the war concluded the same year with the Peace of Passau in August, or dragged on until the Peace of Augsburg in September 1555. The Protestant princes were supported by King Henry II of France, who was a Catholic, but sought to use the opportunity to expand his territory in modern-day Lorraine.