A fortification is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin fortis ("strong") and facere.

The Sole Valley is a valley in Trentino, northern Italy.

Malborghetto Valbruna is a comune (municipality) in the Regional decentralization entity of Udine in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, north-east Italy.

Nauders is a municipality in the district of Landeck in the Austrian state of Tyrol.

The Alpine Wall was an Italian system of fortifications along the 1,851 km (1,150 mi) of Italy's northern frontier. Built in the years leading up to World War II at the direction of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, the defensive line faced France, Switzerland, Austria, and Yugoslavia. It was defended by the "Guardia alla Frontiera" (GaF), Italian special troops.

Lake Predil is a lake near Cave del Predil, part of the Tarvisio municipality in the Province of Udine, in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

The Fortified Sector of Montmédy was the French military organisation that in 1940 controlled the section of the Maginot Line between Sedan and Longuyon, a distance of about 60 kilometres (37 mi). The sector was not as strongly defended as other sections of the Maginot Line, facing the southern Ardennes region of Belgium. Large portions of the Montmédy sector were defended by fortified houses, blockhouses or casemates. The sector includes only four ouvrages of the type found in stronger sections of the Line. The weakly defended area in front of Sedan was the scene of a major breakthrough by German forces in the opening of the Battle of France. This was followed by a German assault on the Maginot Ouvrage La Ferté, which killed the entire garrison, the only such event on the Maginot Line.

The Fortified Sector of the Dauphiné was the French military organization that in 1940 controlled the section of the Alpine Line portion of the Maginot Line facing Italy in the vicinity of Briançon. By comparison with the integrated defenses of the main Maginot Line, or even of the Fortified Sector of the Maritime Alps to the south, the Dauphiné sector consisted of a series of distinct territories that covered two main invasion routes into France: the route from Turin over the Col de Montgenèvre to Briançon and Grenoble, and the route from Coni over the Col de Larche to Barcelonette and Gap. The sector was the scene of probing attacks by Italian forces during the Italian invasion of France in 1940, in which the French defenses successfully resisted Italian advances until the June 1940 armistice that granted Italy access to southeastern France.

The Battle of Tarvis from 16 to 17 May 1809, the Storming of the Malborghetto Blockhouse from 15 to 17 May 1809, and the Storming of the Predil Blockhouse from 15 to 18 May saw the Franco-Italian army of Eugène de Beauharnais attacking Austrian Empire forces under Albert Gyulai. Eugène crushed Gyulai's division in a pitched battle near Tarvisio, then an Austrian town known as Tarvis. At nearby Malborghetto Valbruna and Predil Pass, small garrisons of Grenz infantry heroically defended two forts before being overwhelmed by sheer numbers. The Franco-Italian capture of the key mountain passes allowed their forces to invade Austrian Kärnten during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Tarvisio is located in far northeast Italy, near the borders of both Austria and Slovenia.

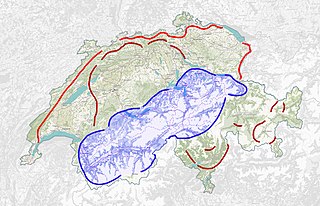

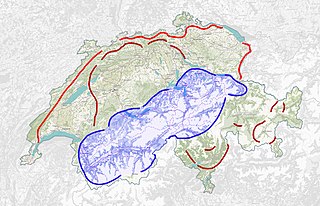

The Swiss National Redoubt is a defensive plan developed by the Swiss government beginning in the 1880s to respond to foreign invasion. In the opening years of the Second World War the plan was expanded and refined to deal with a potential German invasion. The term "National Redoubt" primarily refers to the fortifications begun in the 1880s that secured the mountainous central part of Switzerland, providing a defended refuge for a retreating Swiss Army.

The Infanterie-Werk Belle-Croix, renamed Fort Lauvallière after 1919, is a military installation near Metz. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz.

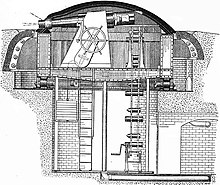

The forts of Metz are two fortified belts around the city of Metz in Lorraine. Built according to the design and theory of Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières at the end of the Second Empire—and later Hans von Biehler while Metz was under German control—they earned the city the reputation of premier stronghold of the German reich. These fortifications were particularly thorough given the city's strategic position between France and Germany. The detached forts and fortified groups of the Metz area were spared in World War I, but showed their full defensive potential in the Battle of Metz at the end of World War II.

The Fortified Section of Savoy(Secteur fortifié de la Savoie) was the French military organization that in 1940 controlled the section of the Alpine Line portion of the Maginot Line facing Italy in the Savoy region. The sector constituted part of the Alpine Line portion of the Maginot Line, between the Defensive Sector of the Rhône to the north, and the Fortified Sector of the Dauphiné to the south. The works combined a number of pre-1914 fortifications with Maginot-style ouvrages, with many forward-positioned cavern-style frontier stations or avant-postes that proved effective in holding invading forces near the order.

The White War is the name given to the fighting in the high-altitude Alpine sector of the Italian front during the First World War, principally in the Dolomites, the Ortles-Cevedale Alps and the Adamello-Presanella Alps. More than two-thirds of this conflict zone lies at an altitude above 2,000m, rising to 3905m at Mount Ortler. In 1917 New York World correspondent E. Alexander Powell wrote: “On no front, not on the sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia, nor in the frozen Mazurian marshes, nor in the blood-soaked mud of Flanders, does the fighting man lead so arduous an existence as up here on the roof of the world.”

Between the 1860s and the First World War the Kingdom of Italy built a number of fortifications along its border with Austria-Hungary. From 1859 the fortified border ran south from Switzerland to Lake Garda, between Italian Lombardy and Austrian South Tyrol. After 1866 it extended to include the border between South Tyrol and Veneto, from Lake Garda to the Carnic Alps. This frontier was difficult to defend, since Austria-Hungary held the higher ground, and an invasion would immediately threaten the industrial and agricultural heartlands of the Po valley. Between 1900 and 1910, Italy also built a series of fortifications along the defensive line of the Tagliamento to protect against an invasion from the northeast. The border with Switzerland was also fortified in what is known as the Cadorna Line.

The Operations in Valtellina was a battle of the Third Italian War of Independence and consisted in the penetration of Austrian units of the 8th Division of General Franz Kuhn von Kuhnenfeld operating in Trentino against the Italian Volunteer Corps of Giuseppe Garibaldi and in the subsequent Italian counterattack of the Mobile National Guard commanded by Colonel Enrico Guicciardi.

The Forra del Lupo is a military walkway consisting of an Austro-Hungarian trench, starting from Serrada and stretching to the 1,670 meters Dosso del Sommo fort, and was part of one of the most important Austrian "works" of the entire "southern" front of the World War I, within the municipal territory of Folgaria and Terragnolo in Trentino.

The Fortress of Trento is the fortified wall built around the city of Trento starting in 1860 and strategically active until its dissolution in 1916.

The Austro-Hungarian fortress of Lavarone, better known as Forte Belvedere Gschwent, stands at an altitude of 1177 metres south of the Oseli subdivision on a rocky spur that extends towards the Valdastico and the Rio Torto valley, dominating its headlands. The fort belongs to the large system of Austro-Hungarian fortifications on the Italian border.