The Province of Upper Canada was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Quebec since 1763. Upper Canada included all of modern-day Southern Ontario and all those areas of Northern Ontario in the Pays d'en Haut which had formed part of New France, essentially the watersheds of the Ottawa River or Lakes Huron and Superior, excluding any lands within the watershed of Hudson Bay. The "upper" prefix in the name reflects its geographic position along the Great Lakes, mostly above the headwaters of the Saint Lawrence River, contrasted with Lower Canada to the northeast.

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the rebellion in Lower Canada, which started the previous month, that emboldened rebels in Upper Canada to revolt.

Charles Duncombe was a leader in the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837 and subsequent Patriot War. He was an active Reform politician in the 1830s, and produced several important legislative reports on banking, lunatic asylums, and education.

The Family Compact is the term used by historians for a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in Lower Canada. It was noted for its conservatism and opposition to democracy.

The Bank of Upper Canada was established in 1821 under a charter granted by the legislature of Upper Canada in 1819 to a group of Kingston merchants. The charter was appropriated by the more influential Executive Councillors to the Lt. Governor, the Rev. John Strachan and William Allan, and moved to Toronto. The bank was closely associated with the group that came to be known as the Family Compact, and it formed a large part of their wealth. The association with the Family Compact and its underhanded practices made Reformers, including Mackenzie, regard the Bank of Upper Canada as a prop of the government. Complaints about the bank were a staple of Reform agitation in the 1830s because of its monopoly and aggressive legal actions against debtors.

The Farmer's Joint Stock Bank was a bank that operated in Upper Canada, and later in the Province of Canada, from 1834 to 1854.

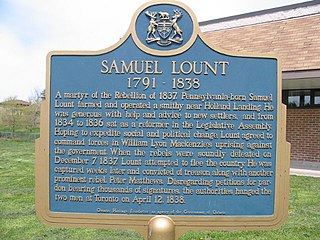

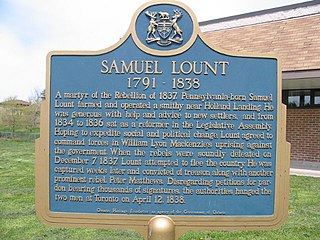

Samuel Lount was a blacksmith, farmer, magistrate and member of the Legislative Assembly in the province of Upper Canada for Simcoe County from 1834 to 1836. He was an organizer of the failed Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, for which he was hanged as a traitor. His execution made him a martyr to the Upper Canadian Reform movement.

Thomas David Morrison was a doctor and political figure in Upper Canada. He was born in Quebec City around 1796 and worked as a clerk in the medical department of the British Army during the War of 1812. He studied medicine in the United States and returned to York in 1824 to become a doctor in Upper Canada. He treated patients and served on the Toronto Board of Health during the 1832 and 1834 cholera outbreaks and co-founded the York Dispensary. In 1834 he was elected to the 12th Parliament of Upper Canada, representing the third riding of York County as part of the reform movement. That same year he was elected as an alderman to the Toronto City Council and reelected the subsequent two years. In 1836, he served a term as mayor of Toronto.

William Warren Baldwin was a doctor, businessman, lawyer, judge, architect and reform politician in Upper Canada. He, and his son Robert Baldwin, are recognized for having introduced the concept of "responsible government", the principle of cabinet rule on which Canadian democracy is based.

John McIntosh was a Scottish-Canadian businessman, ship's captain and political figure in Upper Canada. He was a leading figure of the Upper Canadian reform movement, and was described by his contemporaries as a moderate reformer. He was elected to the province's legislature in 1834, but was unable to be elected to the parliament of the Province of Canada in 1841. He continued supporting reformers, allowing William Lyon Mackenzie to stay in his home upon Mackenzie's return to Canada in 1849.

James Hervey Price was a Canadian attorney and political figure in Canada West. He was born and grew up in Cumberland, United Kingdom, and studied law at Doctors' Commons. He moved to Upper Canada in 1828 and became an attorney in 1833. He was appointed the city of Toronto's first city clerk in 1834 and the following year built a house north of Toronto that he named Castlefield. In 1836 he was elected as a city councillor for St. David's Ward in Toronto but was defeated the following year. Although he considered himself a Reformer, he did not participate in the Upper Canada Rebellion. In 1841 he was elected to the first Parliament of the Province of Canada, representing the 1st riding of York as a Reformer. He served as the commissioner of Crown lands from 1848 to 1851 when he was defeated in his reelection campaign for his seat in the Parliament. He withdrew from politics and worked as an attorney until his retirement in 1857. In 1860 he returned to Britain to Bath, and died in Shirley, Hampshire, in 1882.

James Lesslie was an Ontario bookseller, reform politician and newspaper publisher. His career was closely associated with - and somewhat overshadowed by - William Lyon Mackenzie, the Reform agitator, mayor of Toronto, and Rebellion leader. However, as a leader himself, Lesslie took a prominent role in founding the Mechanics Institute, the House of Refuge & Industry, the Bank of the People, as well as the political parties known as the Canadian Alliance Society and Clear Grits. In many way, he defined the Reform movement in Upper Canada without having reverted to the violent methods of Mackenzie. His legacy may thus have lasted longer.

David Willson (1778–1866) was a religious and political leader who founded the Quaker sect known as, 'The Children of Peace' or 'Davidites,' based at Sharon in York County, Upper Canada in 1812. As the primary minister to this group, he led them in constructing a series of remarkable buildings, the best known of which is the Sharon Temple, now a National Historic Site of Canada. A prolific writer, sympathizer and leader of the movement for political reform in Upper Canada, Willson and his followers ensured the election of William Lyon Mackenzie, and both "fathers of Responsible Government", Robert Baldwin and Louis LaFontaine, in their riding.

The Children of Peace (1812–1889) was an Upper Canadian Quaker sect under the leadership of David Willson, known also as 'Davidites', who separated during the War of 1812 from the Yonge Street Monthly Meeting in what is now Newmarket, Ontario, and moved to the Willsons' farm. Their last service was held in the Sharon Temple in 1889.

The Reform movement in Upper Canada was a political movement in British North America in the mid-19th century.

The Farmers’ Storehouse was Canada's first farmers' cooperative, founded in Toronto and the Home District in 1824. It stood at the centre of a broad economic and political reform movement that, in its essentials, was not greatly different from contemporary movements such as the Owenite socialists in Britain, as well as much later cooperative movements such as the United Farmers of Alberta in the early twentieth century.

A series of parliamentary reports describe the scope of the problem of debt in Upper Canada; as early as 1827, the eleven district jails in the province had a capacity of 298 cells, of which 264 were occupied, 159 by debtors. In the Home District, 379 of 943 prisoners between 1833 and 1835 were being held for debt. Over the province as a whole, 48% or 2304 of 4726 prisoners were being held in jail for debt in 1836. The number of debtors jailed was the result of both widespread poverty, and the small amounts for which debtors could be indefinitely detained.

Samuel Hughes (1785–1856) was a prominent member of the Children of Peace, a reform politician in Upper Canada, and the president of Canada's first farmers cooperative, the Farmers' Storehouse Company. After the Rebellions of 1837 he rejoined the Hicksite Quakers and became a minister of note.

There were two types of corporations at work in the Upper Canadian economy: the legislatively chartered companies and the unregulated joint stock companies. These two business forms had different legal standing; chartered corporations had a "separate personality" - they were a legal person quite distinct from its members or shareholders, a legal fiction which protected those shareholders with limited liability. In contrast, joint stock companies were made illegal by the English Bubble Act of 1720. Joint stock companies were considered extensive partnerships under common law, and English legislation limited these to a maximum of six partners. Without incorporation, the company was not considered a "separate personality." It could not hold property; this was held by trustees, who usually had to provide a bond or security. Without incorporation, the company could neither sue nor be sued at law. And without incorporation, shareholders were personally responsible for the debts to the company to the full extent of their personal property; shareholders were not protected by limited liability. There were, then, significant legal hurdles that made the joint stock company an unwieldy form of partnership.

In 1834, the United Kingdom passed a new Poor Law which created the system of Victorian workhouses that Charles Dickens described in Oliver Twist. Sir Francis Bond Head, the new lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada in 1836, had been a Poor Law administrator before his appointment. Fearing that Head wanted to introduce these workhouses in Toronto, a small group of reformers and dissenting ministers led by publisher James Lesslie and Dr. William W. Baldwin founded the Toronto House of Industry on alternate, humane principles. The Toronto House of Industry was started by the reformers in the ‘unused’ courthouse on Richmond Street in January 1837 where they had previously met as the "Canadian Alliance Society" of which Lesslie had been president. The Toronto House of Refuge and Industry appears to have been founded on the model of the Owenite Socialist "Home Colonies". A constant struggle between the ruling elite, the "Family Compact", and the Reformers to gain control of the institution prevented this plan from ever fully being implemented.