Ritual

Bear ceremonialism in Siberia varies by group, but central to these practices is the recognition of bear ceremonialism as a sacred undertaking, demanding adherence to established protocols and etiquette.

In indigenous Siberian cultures, a fundamental tenet governing the relationship between humans and bears is the prohibition against hunting bears, except under specific circumstances. Bears are only pursued if they pose a direct threat to human life or property, such as in cases where they have caused harm or invaded dwellings. [18]

The traditional ceremony begins a few years before the sacrifice of the bear itself. The bear ceremony starts with a capture, whereby male hunters enter a forest to find a bear den, kill the mother bear and catch the bear cub to bring back to the indigenous encampment. [16] : 23 The people in the region then raise the bear cub as if the bear cub is one of the tribes’ own children. The duration of raising the bear varies between different cultures, but the process can take anywhere from one to five years, depending on the age at which the bear reaches sexual maturity, as well as the sex of the bear. In most cultures, female bears are raised for a shorter amount of time compared to the male bears that are captured by the indigenous peoples. (A note on the duration of raising the bear cub: As mentioned before, the duration by which villages would choose to raise the bear cub also varies culture by culture. For example, the people of Gvasyugi choose to raise the bear for one to two years. [16] : 23 Similarly, the Ulch people of the Amur region opt for a longer period, typically three to four years, before they perform the ritual sacrifice. [16] : 154 These differences in duration reflect the diverse traditions and customs found across different communities, shaping their respective approaches to this practice.)

The bear is raised in captivity in the encampment alongside the people’s animals and children. Usually, a family would raise the bear cub before sacrificing it, either within the confines of the family abode until the bear grew too big to be kept inside. According to one account of the Ulchi bear ceremony, “[the] bear slept with the dogs and came out to play and to be hand fed by the woman of the house". [16] : 154 There have also been records of the bear cubs sucking on female human milk, and indigenous families’ children are reprimanded when they express jealousy toward how bears are treated in the encampment. [19]

Once the bear becomes too large to be kept inside a cage with the family pets, it would be transferred to a special hut until it reached sexual maturity, or was considered ready to be sacrificed — the standards for this decision vary region by region, and, even within regions, culture by culture.

To prepare the bear for its sacrifice to the masters of the taiga, the people of the village may take different approaches depending on the culture. Importantly, bear ceremonialism is one of the few practices in indigenous cultures in Siberia that discourage and subvert the central role that shamans generally play in pagan societies in the northern hemisphere. This is particularly noted in bear ceremonialism practiced in the Amur region. Regarded as spiritual mediators between humans and spirits in Siberian cultures, the bear ceremony prohibits seances performed by shamans as this worship represents one of the few practices where humans are able to communicate directly with spirits without necessitating aid from a third party agent. [20] [19]

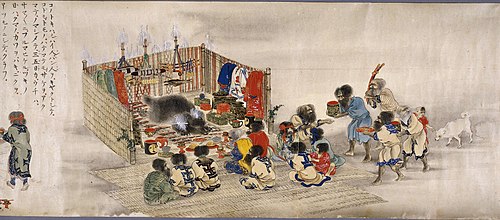

Before the sacrificial ritual, the people of the village generally invest a lot of effort into traditions that serve the purpose of “amusing” the bear. For example, some people would pour water on each other, or the men would wrestle one another in a show of strength in order to make the soon-to-be-sacrificed bear happy. [19] Other means of entertaining the bear also include dog races and games. [19] The purpose of amusing the bear is to ensure that the bear’s sendoff is pleasant, guaranteeing good fortune from the spirits following the bear’s later sacrifice. [19]

In some societies, the bear is then taken from home to home of the village in order to say final goodbyes before the bear is guided to a location in the forest that is not too far away from the encampment (generally the location of the sacrifice is situated within a mile of the village encampment itself). [21] During the sacrifice, it is crucial that the bear is shown respect. Some means of disrespecting the bear would include, for example, being barefoot or using a gun to shoot the bear. [22] As such, the bear has to be killed with a bow and arrow, knife, or spear. Also equally important is the vocabulary used to describe the act of sacrificing the bear. It is common for indigenous peoples to use euphemisms such as “I obtained a child” to convey killing a bear, as using direct language can offend the sacred animal, as well as the gods and spirits presiding over the environment. [23]

The bear is sacrificed with an injury to its heart, after which the people at the ceremony follow a ritual of skinning the animal, cooking it, and feasting on the bear meat. [24] As a celebration following the sacrifice, many activities can take place. Children put on plays, women play musical instruments, and specific dances, myths, and songs are performed as part of the bear ceremony. [19] Some scholarly records additionally indicate that the bear head is often separated from the rest of the body and used as a protective ornament in the home of the family hosting the celebratory feast. [24] Meanwhile, the tongue is gifted to the eldest male of the village as a sign of respect in the culture. [24]

Variation across cultures

Although most indigenous peoples generally follow the same rituals and practices in executing ceremonies for bear worship, some populations also adopt unique versions of the practice with different spiritual, cultural, and social implications across various regions.

- Ob-Ugrians: The Khanty and Mansi believe that the bear is a descendant from the supreme god Torum (also known as Num-Torum), whose children are sent to the earth as a means of surveilling and communicating with people inhabiting it. [25] Importantly, Ob-Ugrians also believe that they have also descended from the god Torum, a belief that forms the basis of these peoples’ social relationship with bears, which is that of a patrilineal kinship. [24] That is, the bear acts as a genetic ancestor to the Ob-Ugrians.

- Tungusic peoples of the Amur: On the other hand, indigenous peoples of the Amur seek to worship the bear not as an act of kinship, but as a means of reverence to their natural environment. When sacrificing the bear, the Tungusic peoples generally do it with the purpose of returning the bear to the masters of the taiga in order to ensure a plentiful and fruitful hunting season. [26] Also importantly, the Evenkis, Nivkhs, and Orochon all believe that all other animals have descended from the bear. For example, when any other game is hunted and killed in the forest, this game would then be considered children of the bear. In this way, by honoring and sacrificing the bear through bear ceremonialism, these indigenous peoples then pay reverence to all animals inhabiting the forest and nature, ensuring fruitful seasons in all kinds of game to come.

- Evenkis: The Evenkis, by contrast, do not raise the bear before sacrificing it. [27] Like the Ob-Ugrians, these indigenous people see the bear as an ancestor. When they hunt and kill the bear in its den, they must show it respect as well, by “addressing it in kinship terms and asking its forgiveness before preparing its carcass and portioning out the meat for the [bear] feast.” [28]

History

Colonial period

As a pagan practice, tsarist Christianizing efforts often sought to suppress bear ceremonialism in Siberia due to it undermining Russian Orthodox hegemony at the time. Until the early 18th century, the Russian tsardom did not necessarily seek to propagate Christian Orthodoxy among indigenous Siberian populations. [29] Native Siberian paganism was not perceived as a faith altogether up until this spiritual worldview began to be perceived as a threat to the legitimacy of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Soviet period

Similarly, Soviet control of the Russian state also led to repressive attitudes toward bear worship among indigenous Siberian peoples. Although religion was tolerated in theory, the socialist state sought to limit paganism as this practice was antithetical to the ideal of Marxist-Leninist atheism adopted as the official attitude toward religion and spiritualism more widely in the Soviet Union. Bear worship, and paganism more generally, was also perceived as a threat to Marxist-Leninist ideology with regards to humans’ relationship with their surrounding natural environment. According to Stephen Dudeck, an anthropologist specializing in indigenous Siberian cultures, "The opposition between the ideological place of nature as a force to be conquered according to Soviet ideology, and the complex and negotiated social relationship with the environment reflected in Indigenous rituals, should not have gone unnoticed (even if people like Steinitz might have ignored this). On a practical level feasting was blamed for distracting workers in the newly created state-controlled enterprises from disciplined work (Slezkine 1994)". [24]

Present day

Indigenous Siberian populations have had a contentious relationship with the Russian state since the beginning of the colonial era. However, in the modern day, the sources of cultural contention have had economic implications as well. The act of raising a bear cub in a village is now deeply costly for the participants of the ceremony, for example. [30]

Meanwhile, bear hunting has led to conflicts between indigenous Siberian cultures and the Russian law as well. For instance, the Khanty have subsistence hunting rights in their traditional region, but the Russian legal framework imposes a heavy financial burden on this indigenous Siberian culture by mandating “expensive and difficult to procure individual species licenses for non-food hunting and trapping.” [30] According to reports by Wiget and Balalaeva, recently, there have been records of Ob-Ugrians being arrested for hunting bears that have previously posed a dangerous threat to people in the village, which is a central pillar of “revenge on the bear.” [31] The “revenge on the bear” constitutes one of the beliefs in bear worship, whereby bears are never to be hunted unless they harm the humans first. This practice is particularly characteristic of societies living in the Amur region of Siberia.

The financial burden on indigenous populations by the Russian Federation is additionally exacerbated by ecological deterioration. The ecological deterioration has been caused by the state’s exploitation of natural resources in Siberia, especially recently. Notably, the Russian oil and gas extraction industry has greatly undermined the state of bears’ natural habitats in the Siberian taiga, leading to the animals’ increased wandering into human villages and potentially attacking the inhabitants. [32] Due to longstanding and deeply rooted custom, these inhabitants must then hunt and kill the trespassing bears. As a result, attacked inhabitants sometimes illegally practice acts of bear hunting due to the legal framework underlying this act within the borders of the Russian Federation. One member of the Khanty indigenous Siberian group remarks: “We protest the destruction of the natural environment in our area, which is turning into our own destruction. We understand that the country needs oil, but not at the expense of our lives! All local industrial works operate as if we weren’t here, as if our ancestors weren’t here, as if our existence were over. Where are the principles of government policy toward Native peoples?” [33]

Revival in recent years

Centuries-long state repression of cultural traditions and spiritualism has led to an overall decline in bear worship among indigenous populations in Siberia. Throughout the 20th century, bear ceremonialism in Siberia became a rarely observed phenomenon. [24] The Ob-Ugrian intelligentsia began the revival process for bear worship in the 1980s and 1990s, when state repression measures of indigenous cultures had been relieved. Since then, the participation of tourists in Khanty bear ceremonies has also increased in the modern day. [26]

Bear ceremonialism has thus taken on an economic significance for indigenous subsistence in modern times as well as tourists would pay to see bear worship in action. Revival activities often come about through state support, as well as televised through state-sponsored media channels. As a result of governmental support, bear worship across various cultures in the northern hemisphere has seemed to “account for both some convergence of forms and some variations (Moldanova 2016; Wiget and Balalaeva 2004a) …. especially okrugwide festival programs in Khanty-Mansiĭsk, probably accounts for the convergent use throughout the northern regions of festival shirts, decorated with rickrack, and felt hats, decorated with traditional symbols.” [34]