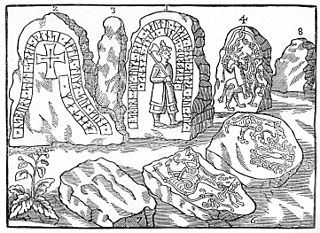

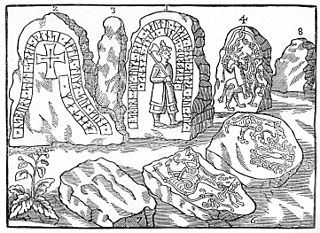

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition of erecting runestones as a memorial to dead men began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but the majority of the extant runestones date from the late Viking Age. While most of these are located in Scandinavia, particularly Sweden, there are also scattered runestones in locations that were visited by Norsemen. Runestones were usually brightly coloured when erected, though this is no longer evident as the colour has worn off.

Danish Runic Inscription 66 or DR 66, also known as the Mask stone, is a granite Viking Age memorial runestone that was discovered in Aarhus, Denmark. The inscription features a facial mask and memorializes a man who died in a battle.

The Sparlösa Runestone, listed as Vg 119 in the Rundata catalog, is located in Västergötland and is the second most famous Swedish runestone after the Rök runestone.

The Eggeby stone, designated as U 69 under the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone that is located at Eggeby, which is 2 kilometers northwest of Central Sundbyberg, Sweden, which was in the historic province of Uppland.

The Jarlabanke Runestones is the name of about 20 runestones written in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark rune script in the 11th century, in Uppland, Sweden.

The Hakon Jarl runestones are Swedish runestones from the time of Canute the Great.

The Ingvar runestones is the name of around 26 Varangian Runestones that were raised in commemoration of those who died in the Swedish Viking expedition to the Caspian Sea of Ingvar the Far-Travelled.

The Hunnestad Monument, listed as DR 282 through 286 in the Rundata catalog, was once located at Hunnestad at Marsvinsholm north-west of Ystad, Sweden. It was the largest and most famous of the Viking Age monuments in Scania, and in Denmark, only comparable to the Jelling stones. The monument was destroyed during the end of the 18th century by Eric Ruuth of Marsvinsholm, probably between 1782 and 1786 when the estate was undergoing sweeping modernization, though the monument survived long enough to be documented and depicted.

The Orkesta Runestones are a set of 11th-century runestones engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark alphabet that are located at the church of Orkesta, northeast of Stockholm in Sweden.

The Hagby Runestones are four runestones that are raised on the courtyard of the farm Hagby in Uppland, Sweden. They are inscribed in Old Norse using the Younger Futhark and they date to the 11th century. Three of the runestones are raised in memory of Varangians who died somewhere in the East, probably in Kievan Rus'.

The Greece runestones are about 30 runestones containing information related to voyages made by Norsemen to the Byzantine Empire. They were made during the Viking Age until about 1100 and were engraved in the Old Norse language with Scandinavian runes. All the stones have been found in modern-day Sweden, the majority in Uppland and Södermanland. Most were inscribed in memory of members of the Varangian Guard who never returned home, but a few inscriptions mention men who returned with wealth, and a boulder in Ed was engraved on the orders of a former officer of the Guard.

The Risbyle Runestones are two runestones found near the western shore of Lake Vallentunasjön in Uppland, Sweden, dating from the Viking Age.

The Varangian Runestones are runestones in Scandinavia that mention voyages to the East or the Eastern route, or to more specific eastern locations such as Garðaríki in Eastern Europe.

The Viking runestones are runestones that mention Scandinavians who participated in Viking expeditions. This article treats the runestone that refer to people who took part in voyages abroad, in western Europe, and stones that mention men who were Viking warriors and/or died while travelling in the West. However, it is likely that all of them do not mention men who took part in pillaging. The inscriptions were all engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark. The runestones are unevenly distributed in Scandinavia: Denmark has 250 runestones, Norway has 50 while Iceland has none. Sweden has as many as between 1,700 and 2,500 depending on definition. The Swedish district of Uppland has the highest concentration with as many as 1,196 inscriptions in stone, whereas Södermanland is second with 391.

There were probably two Gunnar's bridge runestones at Kullerstad, which is about one kilometre northeast of Skärblacka, Östergötland County, Sweden, which is in the historic province of Östergötland, where a man named Håkon dedicated a bridge to the memory of his son Gunnar. The second stone was discovered in a church only 500 metres away and is raised in the cemetery. The second stone informs that Håkon raised more than one stone in memory of his son and that the son died vestr or "in the West."

The Uppland Runic Inscription 328 stands on a hill in a paddock at the farm Stora Lundby, which is about four kilometers west of Lindholmen, Stockholm County, Sweden, in the historic province of Uppland. The runestone is one of several runestones that have permitted scholars to trace family relations among some powerful Viking clans in Sweden during the 11th century.

The Västra Nöbbelöv Runestone, listed as DR 278 in the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone located in Västra Nöbbelöv, which is about 3 kilometers east of Skivarp, Skåne County, Sweden, and was in the historic province of Scania.

Uppland Runic Inscription 1158 or U 1158 is the Rundata catalogue listing for a Viking Age memorial runestone that is located at Stora Salfors, which is one kilometre east of Fjärdhundra, Uppsala County, Sweden, and is in the historic province of Uppland. The stone is a memorial to a man named Freygeirr, and may have been the same Freygeirr who was a Viking chieftain active on the Baltic coast in the 1050s.

The Replösa Stone is a runestone in Replösa near Ljungby, Sweden.