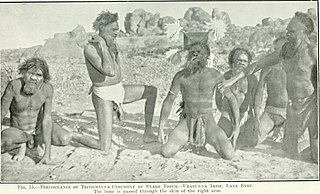

The Dreaming, also referred to as Dreamtime, is a term devised by early anthropologists to refer to a religio-cultural worldview attributed to Australian Aboriginal beliefs. It was originally used by Francis Gillen, quickly adopted by his colleague Sir Baldwin Spencer and thereafter popularised by A. P. Elkin, who, however, later revised his views.

The Diyari, alternatively transcribed as Dieri, is an Indigenous Australian group of the South Australian desert originating in and around the delta of Cooper Creek to the east of Lake Eyre.

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer, commonly referred to as Sir Baldwin Spencer, was a British-Australian evolutionary biologist, anthropologist and ethnologist. He is known for his fieldwork with Aboriginal peoples in Central Australia, contributions to the study of ethnography, and academic collaborations with Frank Gillen. Spencer introduced the study of zoology at the University of Melbourne and held the title of Emeritus Professor until his death in 1929. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1900 and knighted in 1916.

The Arrerntepeople, sometimes referred to as the Aranda, Arunta or Arrarnta, are a group of Aboriginal Australian peoples who live in the Arrernte lands, at Mparntwe and surrounding areas of the Central Australia region of the Northern Territory. Many still speak one of the various Arrernte dialects. Some Arrernte live in other areas far from their homeland, including the major Australian cities and overseas.

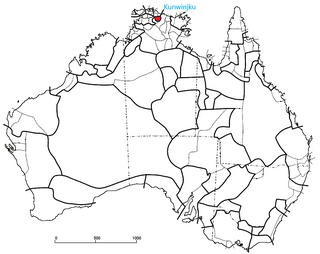

The Kunwinjku people are an Australian Aboriginal people, one of several groups within the Bininj people, who live around West Arnhem Land to the east of Darwin, Northern Territory. Kunwinjku people generally refer to themselves as "Bininj" in much the same way that Yolŋu people refer to themselves as "Yolŋu".

The Garrwa people, also spelt Karawa and Garawa, are an Aboriginal Australian people living in the Northern Territory, whose traditional lands extended from east of the McArthur River at Borroloola to Doomadgee and the Nicholson River in Queensland.

The Yardliyawara, also known as the Jadliaura and variant spellings, are an Aboriginal Australian people of South Australia.

The Gajirrawoong people, also written Gadjerong, Gajerrong and other variations, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory, most of whom now live in north-eastern Western Australia.

The Tjial were an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory who are now extinct.

The Bingongina or Pinkangarna are a possible indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory. However, the name may simply be a former alternative term for Mudburra.

The Arabana, also known as the Ngarabana, are an Aboriginal Australian people of South Australia.

The Wangkangurru, also written Wongkanguru and Wangkanguru, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Simpson Desert area in the state of South Australia. They also refer to themselves as Nharla.

The Wilingura otherwise known as the Wilangarra, were an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Watta were an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Gaagudju, also known as the Kakadu, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory. There are four clans, being the Bunitj or Bunidj, the Djindibi, and two Mirarr clans. Three languages are spoken among the Mirarr or Mirrar clan: the majority speak Kundjeyhmi, while others speak Gaagudju and others another language.

The Marra, formerly sometimes referred to as Mara, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Gudanji, otherwise known as the Kotandji or Ngandji, are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Wambaya people, also spelt Umbaia, Wombaia and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the southern Barkly Tableland of the Northern Territory. Their language is the Wambaya language. Their traditional lands have now been taken over by large cattle stations.

The Jingili or Jingulu are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Warlmanpa are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.