Related Research Articles

The Yolngu or Yolŋu are an aggregation of Aboriginal Australian people inhabiting north-eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yolngu means "person" in the Yolŋu languages. The terms Murngin, Wulamba, Yalnumata, Murrgin and Yulangor were formerly used by some anthropologists for the Yolngu.

Milingimbi Island, also Yurruwi, is the largest island of the Crocodile Islands group off the coast of Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia.

The Crocodile Islands are a group of islands belonging to the Yan-nhaŋu people of the Northern Territory of Australia. They are located off the coast of Arnhem Land in the Arafura Sea.

Lester Richard Hiatt, known as Les Hiatt, was a scholar of Australian Aboriginal societies who promoted Australian Aboriginal studies within both the academic world and within the wider public for almost 50 years. He is now regarded as one of Australia's foremost anthropologists.

In the anthropological study of kinship, a moiety is a descent group that coexists with only one other descent group within a society. In such cases, the community usually has unilineal descent so that any individual belongs to one of the two moiety groups by birth, and all marriages take place between members of opposite moieties. It is an exogamous clan system with only two clans.

The Burarra people, also referred to as the Gidjingali, are an Aboriginal Australian people in and around Maningrida, in the heart of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Opinions have differed as to whether the two names represent different tribal realities, with the Gidjingali treated as the same as, or as a subgroup of the Burarra, or as an independent tribal grouping. For the purposes of this encyclopedia, the two are registered differently, though the ethnographic materials on both may overlap with each other.

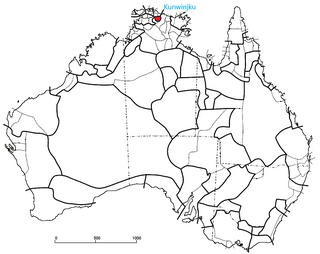

The Kunwinjku people are an Australian Aboriginal people, one of several groups within the Bininj people, who live around West Arnhem Land to the east of Darwin, Northern Territory. Kunwinjku people generally refer to themselves as "Bininj" in much the same way that Yolŋu people refer to themselves as "Yolŋu".

Djinang is an Australian Aboriginal language, one of the family of Yolŋu languages which are spoken in the north-east Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory.

The Gunavidji people, also written Kunibidji and Kunibídji and also known as the Ndjébbana, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.

The Djinba are an Aboriginal Australian group of the Yolngu people of the Northern Territory.

The Yan-nhaŋu, also known as the Nango, are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory. They have strong sociocultural connections with their neighbours, the Burarra, on the Australian mainland.

Ian Keen is an Australian anthropologist, whose research interests cover Yolngu kinship structures and religion, Aboriginal land rights and economies, and language.

The Gadjalivia were an indigenous Australian people of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. They are now regarded as extinct.

The Ritharrngu and also known as the Diakui, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, of the Yolŋu group of peoples. Their clans are Wagilak and Manggura, and Ritharrŋu.

The Dalabon or Dangbon are an Australian Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory.

The Tjial were an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory who are now extinct.

The Daii or Dhay'yi are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Gungorogone are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Jingili or Jingulu are an indigenous Australian people of the Northern Territory.

The Mudburra, also spelt Mudbara and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory.

References

- ↑ Waters 1989, p. 276.

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 224.

- 1 2 Waters 1989, p. xiv.

- ↑ Waters 1989, p. 11.

- ↑ Elliott 2015, p. 104, n.4.

- 1 2 Waters 1989, p. xv.

- ↑ Waters 1989, p. 4.

- 1 2 Waters 1989, p. 48.

- ↑ Waters 1989, p. 252.

- ↑ Waters 1989, p. 288.