In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Mamaragan or Namarrkon is a lightning Ancestral Being who speaks with thunder as his voice. He rides a storm-cloud and throws lightning bolts to humans and trees. He lives in a puddle.

Kakadu National Park is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia, 171 km (106 mi) southeast of Darwin. It is a World Heritage Site. Kakadu is also gazetted as a locality, covering the same area as the national park, with 313 people recorded living there in the 2016 Australian census.

The Rainbow Serpent or Rainbow Snake is a common deity often seen as the creator God, known by numerous names in different Australian Aboriginal languages by the many different Aboriginal peoples. It is a common motif in the art and religion of many Aboriginal Australian peoples. Much like the archetypal mother goddess, the Rainbow Serpent creates land and diversity for the Aboriginal people, but when disturbed can bring great chaos.

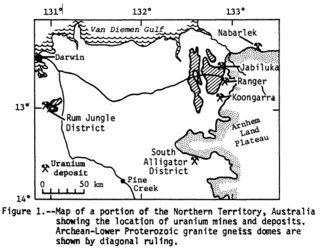

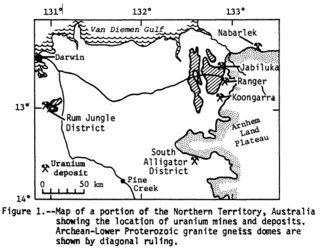

Alligator Rivers is the name of an area in an Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory of Australia, containing three rivers, the East, West, and South Alligator Rivers. It is regarded as one of the richest biological regions in Australia, with part of the region in the Kakadu National Park. It is an Important Bird Area (IBA), lying to the east of the Adelaide and Mary River Floodplains IBA. It also contains mineral deposits, especially uranium, and the Ranger Uranium Mine is located there. The area is also rich in Australian Aboriginal art, with 1500 sites. The Kakadu National Park is one of the few World Heritage sites on the list because of both its natural and human heritage values. They were explored by Lieutenant Phillip Parker King in 1820, who named them in the mistaken belief that the crocodiles in the estuaries were alligators.

Gunbalanya is an Aboriginal Australian town in west Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, about 300 kilometres (190 mi) east of Darwin. The main language spoken in the community is Kunwinjku. At the 2021 Australian census, Gunbalanya had a population of 1,177.

Bininj Kunwok is an Australian Aboriginal language which includes six dialects: Kunwinjku, Kuninjku, Kundjeyhmi, Manyallaluk Mayali (Mayali), Kundedjnjenghmi, and two varieties of Kune. Kunwinjku is the dominant dialect, and also sometimes used to refer to the group. The spellings Bininj Gun-wok and Bininj Kun-Wok have also been used in the past, however Bininj Kunwok is the current standard orthography.

Nicholas Evans is an Australian linguist and a leading expert on endangered languages. He was born in Los Angeles.

The Oenpelli python or Oenpelli rock python is a species of large snake in the family Pythonidae. The species is endemic to the sandstone massif area of the western Arnhem Land region in the Northern Territory of Australia. There are no subspecies that are recognised as being valid. It has been called the rarest python in the world. Two notable characteristics of the species are the unusually large size of its eggs and its ability to change colour. It is the longest snake native to the Northern Territory.

The black wallaroo, also known as Woodward's wallaroo, is a species of macropod restricted to a small, mountainous area in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia, between South Alligator River and Nabarlek. It classified as near threatened, mostly due to its limited distribution. A large proportion of the range is protected by Kakadu National Park.

The Jim Jim Falls is a plunge waterfall on the Jim Jim Creek that descends over the Arnhem Land escarpment within the UNESCO World Heritage–listed Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia. The Jim Jim Falls area is registered on the Australian National Heritage List.

The Kunwinjku people are an Australian Aboriginal people, one of several groups within the Bininj people, who live around West Arnhem Land to the east of Darwin, Northern Territory. Kunwinjku people generally refer to themselves as "Bininj" in much the same way that Yolŋu people refer to themselves as "Yolŋu".

Kune is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Kune are the Bininj people, who live primarily in western Arnhem Land. Kune is spoken primarily in the south-east of the Bininj Kunwok speaking areas, particularly in the Cadell River district south of Maningrida. This includes outstations such as Korlobidahdah, Buluhkaduru and Bolkdjam. Grammatically Kune is closely related to other varieties of Bininj Kunwok, however there are many differences in vocabulary.

Rembarrnga (Rembarunga) is an Australian Aboriginal language. It is one of the Northern Non-Pama–Nyungan languages, spoken in the Roper River region of the Northern territory. There are three dialects of Rembarrnga, namely Galduyh, Gikkik and Mappurn. It is a highly endangered language, with very few remaining fluent speakers. It is very likely that the language is no longer being learned by children. Instead, the children of Rembarrnga speakers are now learning neighbouring languages such as Kriol in south central Arnhem Land, and Kunwinjku, a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, in north central Arnhem Land.

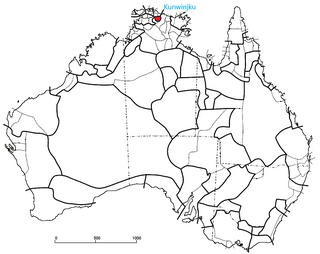

Kunwinjku is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Kunwinjku are the Bininj people, who live primarily in western Arnhem Land. As Kunwinjku is the most widely spoken dialect of Bininj Kunwok, 'Kunwinjku' is sometimes used to refer to Bininj Kunwok as a whole. Kunwinjku is spoken primarily in the west of the Bininj Kunwok speaking areas, including the town of Gunbalanya, as well as outstations such as Mamardawerre, Kumarrirnbang, Kudjekbinj and Manmoyi.

The Yawkyawk is a female creature originating in the mythology of the Kunwinjku people of Western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia.

The Gaagudju, also known as the Kakadu, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory. There are four clans, being the Bunitj or Bunidj, the Djindibi, and two Mirarr clans. Three languages are spoken among the Mirarr or Mirrar clan: the majority speak Kundjeyhmi, while others speak Gaagudju and others another language.

Kuninjku is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Kuninjku are the Bininj people, who live primarily in western Arnhem Land. Kuninjku is spoken primarily in the east of the Bininj Kunwok speaking areas, particularly the outstations of Maningrida such as Mumeka, Marrkolidjban, Mankorlod, Barrihdjowkkeng, Kakodbebuldi, Kurrurldul and Yikarrakkal.

Mayali or Manyallaluk Mayali is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Mayali are the Bininj people, who live primarily in western Arnhem Land. Mayali is spoken primarily in south-west Arnhem Land, particularly around Pine Creek, Katherine and Manyallaluk. Occasionally the term "Mayali" is used to refer to all Bininj Kunwok dialects collectively, however this is not generally accepted usage. Speakers of the Kundjeyhmi dialect of Bininj Kunwok often regard Mayali as similar to, or even the same as, Kundjeyhmi.

Kundjeyhmi is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Kundjeyhmi are Bininj people, who live primarily in Kakadu National Park. Kundjeyhmi is considered an endangered dialect, with young speakers increasingly switching to English, Aboriginal English, Kunwinjku and Australian Kriol. Kundjeyhmi has a number of lexical and grammatical features that differ from the larger Kunwinjku and Kuninjku dialects.

Kundedjnjenghmi is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Kundedjnjenghmi dialect is native to the high 'stone country' of the Arnhem Plateau, including the communities of Kabulwarnamyo and Kamarrkawarn. Younger speakers in this area have largely switched to other varieties of Bininj Kunwok, although they retain a passive knowledge of Kundedjnjenghmi. A number of songs by the Nabarlek band use the Kundedjnjenghmi dialect, as do traditional 'Kunborrk' songs.