Mohammed Amin al-Husseini was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine. Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab nobles, who trace their origins to the Islamic Prophet Muhammad.

A popular uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine against the British administration, later known as the Great Revolt, the Great Palestinian Revolt, or the Palestinian Revolution, lasted from 1936 until 1939. The movement sought independence from British colonial rule and the end of British support for Zionism, including Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews.

ʿIzz ad-Dīn ibn Abd al-Qāder ibn Mustafā ibn Yūsuf ibn Muhammad al-Qassām was a Syrian Muslim preacher and a leader in the local struggles against British and French Mandatory rule in the Levant and an opponent of Zionism in the 1920s and 1930s.

Nahalal is a moshav in northern Israel. Covering 8.5 square kilometers (3.3 sq mi), it falls under the jurisdiction of the Jezreel Valley Regional Council. In 2022 it had a population of 1,351.

Jamal al-Husayni (1894–1982), was born in Jerusalem and was a member of the highly influential and respected Husayni family.

Balad al-Sheikh or Balad ash-Shaykh was a Palestinian Arab village located just north of Mount Carmel, 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) southeast of Haifa. Currently the town's land is located within the jurisdiction of the Israeli city, Nesher.

The Palestinian people are an ethnonational group with family origins in the region of Palestine. Since 1964, they have been referred to as Palestinians, but before that they were usually referred to as Palestinian Arabs. During the period of the British Mandate, the term Palestinian was also used to describe the Jewish community living in Palestine.

During the British rule in Mandatory Palestine, there was civil, political and armed struggle between Palestinian Arabs and the Jewish Yishuv, beginning from the violent spillover of the Franco-Syrian War in 1920 and until the onset of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The conflict shifted from sectarian clashes in the 1920s and early 1930s to an armed Arab Revolt against British rule in 1936, armed Jewish Revolt primarily against the British in mid-1940s and finally open war in November 1947 between Arabs and Jews.

Muhammad 'Izzat Darwaza was a Palestinian politician, historian, and educator from Nablus. Early in his career, he worked as an Ottoman bureaucrat in Palestine and Lebanon. Darwaza had long been a sympathizer of Arab nationalism and became an activist of that cause following the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1916, joining the nationalist al-Fatat society. As such, he campaigned for the union of Greater Syria and vehemently opposed Zionism and foreign mandates in Arab lands. From 1922 to 1927, he served as an educator and as the principal at the an-Najah National School where he implemented a pro-Arab nationalist educational system, promoting the ideas of Arab independence and unity. Darwaza's particular brand of Arab nationalism was influenced by Islam and his beliefs in Arab unity and the oneness of Arabic culture.

The Peasants' Revolt was a rebellion against Egyptian conscription and taxation policies in Palestine. While rebel ranks consisted mostly of the local peasantry, urban notables and Bedouin tribes also formed an integral part of the revolt. This was a collective reaction to Egypt's gradual elimination of the unofficial rights and privileges previously enjoyed by the various classes of society in the Levant under Ottoman rule.

Rashid al-Haj Ibrahim (1889–1953) was a Palestinian Arab banker and a leader of the Independence Party of Palestine (al-Istiqlal). He was one of the most influential Arab leaders of Haifa in the first half of the 20th century and played a leading role in both the 1936–39 Arab revolt and the 1948 Battle of Haifa.

The Cement Incident took place in the port of Jaffa in Palestine on 16 October 1935. While Arab dockers were unloading a consignment of 537 drums of White-Star cement from the Belgian cargo ship Leopold II, which were destined for a Jewish merchant called J. Katan in Tel Aviv, one drum accidentally broke open spilling out guns and ammunition. Further investigation by British Mandate officials revealed a large cache of smuggled weapons, comprising 25 machine guns, 800 rifles and 400,000 rounds of ammunition contained in 359 of the 537 drums, but because the merchant was not identified and the final destination was not uncovered, no arrests were made.

Events in the year 1936 in the British Mandate of Palestine.

Events in the year 1935 in the British Mandate of Palestine.

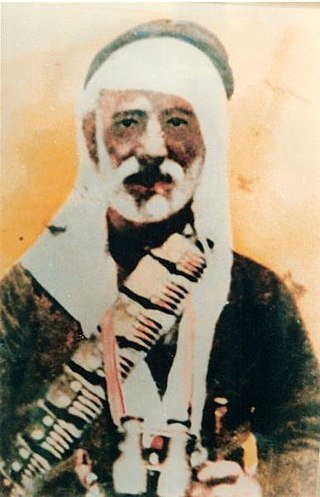

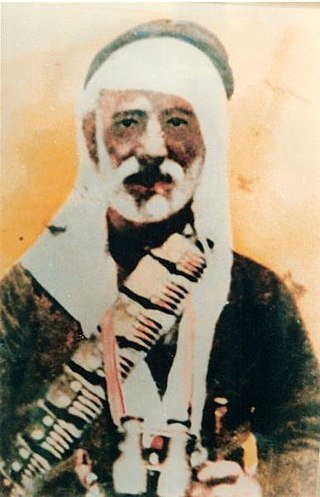

Sheikh Farhan al-Saadi was a Palestinian rebel commander and revolutionary who rose to prominence during the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. He participated in national conferences and demonstrations against the British Mandate of Palestine in the 1929 Palestine riots. He is thought to have been the first to use a weapon during the revolt.

This is a timeline of intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine.

Khalil Muhammad Issa, better known by his nom de guerreAbu Ibrahim al-Kabir, was a Palestinian Arab commander during the 1936-39 Arab revolt in Palestine.

Yusuf Sa'id Abu Durra, also known as Abu Abed was one of the chief Palestinian Arab rebel commanders during the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine. Abu Durra was a close disciple of the Muslim preacher and rebel Izz ad-Din al-Qassam and one of the few survivors of a shootout between British forces and Qassam, in which the latter was killed. When the revolt broke out, Abu Durra led bands of Qassam's remaining disciples and other armed volunteers in the region between Haifa and Jenin. He also administered a rebel court system in his areas of operation, which prosecuted and executed several Palestinian village headmen suspected of colluding with the British authorities. After experiencing battlefield setbacks, Abu Durra escaped to Transjordan, but was arrested on his way back to Palestine in 1939. He was subsequently tried later that year and executed by the authorities in 1940.

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine. Originally formed in the early 20th century in opposition to Zionism, Palestinian nationalism later internationalized and attached itself to other ideologies; it has thus rejected the occupation of the Palestinian territories by the government of Israel since the 1967 Six-Day War. Palestinian nationalists often draw upon broader political traditions in their ideology, such as Arab socialism and ethnic nationalism in the context of Muslim religious nationalism. Related beliefs have shaped the government of Palestine and continue to do so.

The 1936 Tulkarm shooting of two Jews on the road between Anabta and Tulkarm took place in British Mandatory Palestine. Jews retaliated the next day against Arabs in Tel Aviv and killed two in Petah Tikvah.