Buddhist temples are an important part of the Korean landscape. Most Korean temples have names ending in -sa, which means "monastery" in Sino-Korean. Many temples participate in the Templestay program, where visitors can experience Buddhist culture and even stay at the temple overnight.

Deoksugung (Korean: 덕수궁) also known as Gyeongun-gung, Deoksugung Palace, or Deoksu Palace, is a walled compound of palaces in Seoul that was inhabited by members of Korea's royal family during the Joseon monarchy until the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910. It is one of the "Five Grand Palaces" built by the kings of the Joseon dynasty and designated as a Historic Site. The buildings are of varying styles, including some of natural cryptomeria wood), painted wood, and stucco. Some buildings were built of stone to replicate western palatial structures.

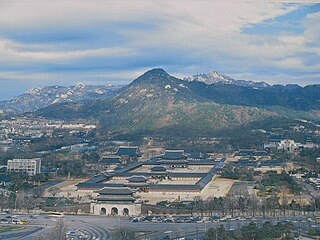

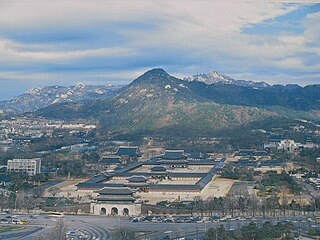

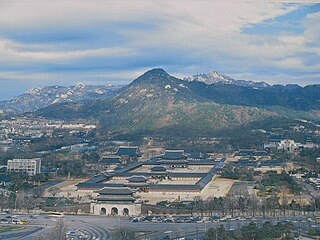

Gyeongbokgung, also known as Gyeongbok Palace or Gyeongbokgung Palace, was the main royal palace of the Joseon dynasty. Built in 1395, it is located in northern Seoul, South Korea. The largest of the Five Grand Palaces built by the Joseon dynasty, Gyeongbokgung served as the home of the royal family and the seat of government.

Changdeokgung, also known as Changdeokgung Palace or Changdeok Palace, is set within a large park in Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. It is one of the "Five Grand Palaces" built by the kings of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897). As it is located east of Gyeongbok Palace, Changdeokgung—along with Changgyeonggung—is also referred to as the "East Palace".

Jongno or Jong-ro is a trunk road and one of the oldest major east–west thoroughfares in Seoul, South Korea. Jongno connects Gwanghwamun Plaza to Dongdaemun.

National Treasure (Korean: 국보) is a national-level designation within the heritage preservation system of South Korea for tangible objects of significant artistic, cultural and historical value. Examples of objects include art, artifacts, sites, or buildings. It is administered by the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). Additions to the list are decided by the Cultural Heritage Committee.

The Korean Bell of Friendship is a massive bronze bell housed in a stone pavilion located in Angel's Gate Park, situated in the San Pedro neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Positioned at the intersection of Gaffey and 37th Streets, this section of the park is also referred to as the "Korean–American Peace Park" and occupies a portion of the former Upper Reservation of Fort MacArthur.

Korean architecture refers to an architectural style that developed over centuries in Korea. Throughout the history of Korea, various kingdoms and royal dynasties have developed a unique style of architecture with influences from Buddhism and Korean Confucianism.

Insa-dong (Korean: 인사동) is a dong, or neighborhood, in Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. Its main street is Insadong-gil, which is connected to a number of alleys that lead deeper into the district, with modern galleries and tea shops. Historically, it was the largest market for antiques and artwork in Korea.

Jogyesa is the chief temple of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. The building dates back to the late 14th century and became the order's chief temple in 1936. It thus plays a leading role in the current state of Seon Buddhism in South Korea. The temple was first established in 1395, at the dawn of the Joseon Dynasty; the modern temple was founded in 1910 and initially called "Gakhwangsa". The name was changed to "Taegosa" during the period of Japanese rule, and then to the present name in 1954.

Jongmyo (Korean: 종묘) is a Confucian royal ancestral shrine in the Jongno District of Seoul, South Korea. It was originally built during the Joseon period (1392–1897) for memorial services for deceased kings and queens. According to UNESCO, the shrine is the oldest royal Confucian shrine preserved and the ritual ceremonies continue a tradition established in the 14th century. Such shrines existed during the Three Kingdoms of Korea period (57–668), but these have not survived. The Jongmyo Shrine was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1995.

Yeongeunmun or Yeongeunmun Gate was a Joseon-era former gate near present day Seoul, South Korea. Since it was a symbol of China's diplomatic influence on the Joseon, the Gaehwa Party of the Joseon government intentionally demolished it in February 1895, seeking complete political independence of Joseon from China.

The Borugak Jagyeongnu, classified as a scientific instrument, is the 229th National Treasure of South Korea and was designated by the South Korean government on March 3, 1985. The water clock is currently held and managed by the National Palace Museum of Korea in Seoul. It dates to the time of King Sejong of the Joseon Dynasty.

Jung District is one of the 25 districts of Seoul, South Korea.

Jongno District is a district in Seoul, South Korea. It is the historic center of Seoul that contains Gyeongbokgung, the main royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and the Blue House, the former presidential residence.

Gwanghwamun is the main and largest gate of Gyeongbok Palace, in Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. It is located at a three-way intersection at the northern end of Sejongno. As a landmark and symbol of Seoul's long history as the capital city during the Joseon period, the gate has gone through multiple periods of destruction and disrepair. The most recent large-scale restoration work on the gate was finished and it was opened to the public on August 15, 2010.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Seoul, South Korea.

Anti-appeasement steles were 19th century monuments built in Korea to ostracize Westerners. They were erected by Heungseon Daewongun at more than 200 major transportation hubs across the country, including the four streets of Jongno. They were built in 1871. They were made of granite and were four cubits high, five cubits wide, and eight inches thick.

Myo is a Korean term for Confucian shrines, where the ritual jesa is held. While this concept is nowadays mainly known for the Joseon dynasty's Jongmyo shrine in Seoul, its history dates back to the Three Kingdoms period.

Heungnyemun is second gate of Gyeongbokgung, Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. It was torn down in the 20th century, but was restored along with Gwanghwamun as part of the restoration project from 2001 to 2021.