The cinema of Croatia has a somewhat shorter tradition than what is common for other Central European countries: the serious beginning of Croatian cinema starts with the rise of the Yugoslavian film industry in the 1940s. Three Croatian feature films were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, several of them gained awards at major festivals, and the Croatian contribution in the field of animation is particularly important.

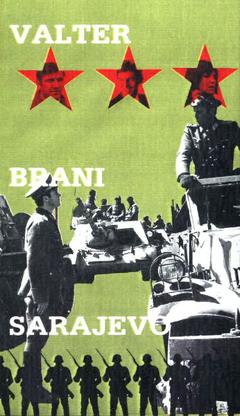

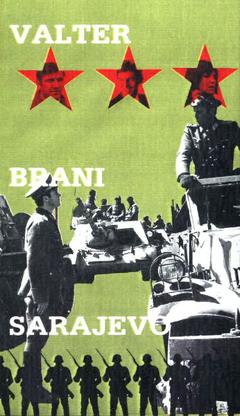

Partisan film is the name for a subgenre of war films made in FPR/SFR Yugoslavia during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In the broadest sense, main characteristics of Partisan films are that they are set in Yugoslavia during World War II and have Yugoslav Partisans as main protagonists, while the antagonists are Axis forces and their collaborators. According to Croatian film historian Ivo Škrabalo, Partisan film is "one of the most authentic genres that emerged from the Yugoslav cinema".

You Love Only Once is a 1981 Yugoslavian drama film directed by Rajko Grlić. It competed in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival. In 1999, a poll of Croatian film critics said it to be one of the best Croatian films ever made.

Ciguli Miguli is a 1952 Yugoslav political satire film directed by Branko Marjanović and written by Joža Horvat. It was meant to be the first satirical film of the post-World War II Yugoslav cinema, but its sharp criticism of bureaucracy was politically condemned by the authorities and the film was banned as "anti-socialist".

Fadil Hadžić was a Croatian and Yugoslav film director, screenwriter, playwright and journalist, mainly known for his comedy films and plays. He was born in Bileća in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but mainly lived and worked in Zagreb, with the Croatian and wider Yugoslav productions.

The Blue 9 is a 1950 Croatian football comedy film. The film was directed by Krešo Golik.

Go, Yellow is a 2001 Croatian football comedy-drama film directed by Dražen Žarković. It was Žarković's debut feature film, after having directed several award-winning documentary and short films. He set out to create an unpretentious, easy-to-watch film that would be popular with the cinemagoers, but it was ultimately poorly received at the Croatian box office and was met with mixed reviews from the critics.

Only People is a 1957 Yugoslav film directed by Branko Bauer, starring Tamara Miletić and Milorad Margetić.

Martin in the Clouds is a 1961 Croatian film directed by Branko Bauer, starring Boris Dvornik and Ljubica Jović.

Face to Face is a 1963 Yugoslavian political film. It is directed by Branko Bauer, written by Bogdan Jovanović, and stars Ilija Džuvalekovski, Husein Čokić, and Vladimir Popović.

Looking Into the Eyes of the Sun is a 1966 Yugoslav film directed by Veljko Bulajić and starring Bata Živojinović, Antun Nalis, Faruk Begolli, Mladen Ladika, and Milena Dravić.

Protest is a 1967 Croatian film directed by Fadil Hadžić, starring Bekim Fehmiu and Antun Vrdoljak.

Accidental Life is a 1969 Yugoslav drama film directed by Ante Peterlić, starring Dragutin Klobučar, Ivo Serdar, Ana Karić and Zvonimir Rogoz.

Journalist (Novinar) is a 1979 Croatian drama film directed and written by Fadil Hadžić and starring Rade Šerbedžija, Fabijan Šovagović and Stevo Žigon.

The Third Key is a 1983 Croatian film directed by Zoran Tadić, starring Božidar Alić and Vedrana Međimorec. A Kafkian horror film, indirectly touching on the topic of corruption, in showing the alienation and soullessness of modern agglomerations it resembles somewhat the film Someone's Watching Me! by John Carpenter.

Slobodan Trninić is a Croatian cinematographer.

Branko Marjanović was a Yugoslav film director and editor.

Živorad Tomić is a Croatian film director, screenwriter and critic. Tomić was one of the most prominent Croatian film critics from the mid-1970s to the late 1990s.

Božidarka Frajt is a Croatian actress.

Hrvoje Turković is a Croatian film theorist, film critic and university professor. With 14 books and more than 700 articles on film, ranging from essayistic criticism to scientific works on film theory, Turković established himself as one of Croatia's most important critics and film scholars. He is a recipient of the Vladimir Nazor Lifetime Achievement Award for Contribution to Film.