A loader is a heavy equipment machine used in construction to move or load materials such as soil, rock, sand, demolition debris, etc. into or onto another type of machinery.

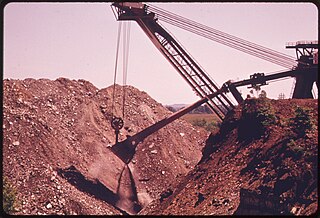

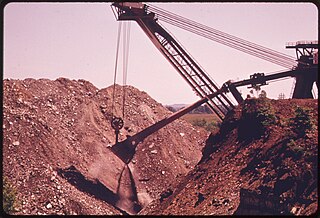

A dragline excavator is a heavy-duty excavator used in civil engineering and surface mining. It was invented in 1904, and presented an immediate challenge to the steam shovel and its diesel and electric powered descendant, the power shovel. Much more efficient than even the largest of the latter, it enjoyed a heyday in extreme size for most of the 20th century, first becoming challenged by more efficient rotary excavators in the 1950s, then superseded by them on the upper end from the 1970s on.

A reclaimer is a large machine used in bulk material handling applications. A reclaimer's function is to recover bulk material such as ores and cereals from a stockpile. A stacker is used to stack the material.

Bagger 288, previously known as the MAN TAKRAF RB288 built by the German company Krupp for the energy and mining firm Rheinbraun, is a bucket-wheel excavator or mobile strip mining machine.

The Silver Spade was a giant power shovel used for strip mining in southeastern Ohio. Manufactured by Bucyrus-Erie, South Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the model 1950-B was one of two of this model built, the other being its sister ship, the GEM of Egypt. Its sole function was to remove the earth and rock overburden from the coal seam. Attempts to purchase and preserve the shovel from Consol to make it the centerpiece of a mining museum exhibit for $2.6 million fell short. A salvage company began scrapping the machine in January 2009. The boom was dropped using explosives on February 9th, ending any rescue attempts. By March 1st, much of the machine had been cut away.

Big Muskie was a dragline excavator built by Bucyrus-Erie and owned by the Central Ohio Coal Company, weighing 13,500 short tons (12,200 t) and standing nearly 22 stories tall. It mined coal in the U.S. state of Ohio from 1969 to 1991. It was dismantled and sold for scrap in 1999.

A landship is a large land vehicle that travels exclusively on land. Its name is meant to distinguish it from vehicles that travel through other mediums such as conventional ships, airships, and spaceships.

TAKRAF Group (“TAKRAF”), is a global German industrial company. Through its brands, TAKRAF and DELKOR, the Group provides equipment, systems and services to the mining and associated industries.

F60 is the series designation of five overburden conveyor bridges used in brown coal (lignite) opencast mining in the Lusatian coalfields in Germany. They were built by the former Volkseigener Betrieb TAKRAF in Lauchhammer and are the largest movable technical industrial machines in the world. As overburden conveyor bridges, they transport the overburden which lies over the coal seam. The cutting height is 60 m (200 ft), hence the name F60. In total, the F60 is up to 80 m (260 ft) high and 240 m (790 ft) wide; with a length of 502 m (1,647 ft), it is described as the lying Eiffel Tower, making these behemoths not only the longest vehicle ever made—beating Prelude FLNG, the longest ship—but the largest vehicle by physical dimensions ever made by humankind. In operating condition, it weighs 13,600 metric tons making the F60 also one of the heaviest land vehicles ever made, beaten only by Bagger 293, which is a giant bucket-wheel excavator. Nevertheless, despite its immense size, it is operated by only a crew of 14.

Bagger 293, previously known as the MAN TAKRAF RB293, is a giant bucket-wheel excavator made by the German industrial company TAKRAF, formerly an East German Kombinat.

P&H Mining Equipment sells drilling and material handling machinery under the "P&H" trademark. The firm is an operating subsidiary of Joy Global Inc. In 2017 Joy Global Inc. was acquired by Komatsu Limited of Tokyo, Japan, and is now known as Komatsu Mining Corporation and operates as a subsidiary of Komatsu.

Spreaders in mining are heavy equipment used in surface mining and mechanical engineering/civil engineering. The primary function of a spreader is to act as a continuous spreading machine in large-scale open pit mining operations.

TAKRAF India Private Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of TAKRAF GmbH. As with its parent company, TAKRAF India provides equipment, systems and services to the mining and associated industries through the TAKRAF and DELKOR brands.

The Visonta Coal Mine ([]) is an open pit lignite mine located near Gyöngyös, Heves County, in Hungary. It is the smallest lignite mine in Hungary out of three lignite mines in total. The mine has coal reserves amounting to 400 million tonnes of lignite, one of the largest coal reserves in Europe and the world and has an annual production of 3.9 million tonnes of coal.

A bucket chain excavator (BCE) is a piece of heavy equipment used in surface mining and dredging. BCEs use buckets on a revolving chain to remove large quantities of material. They are similar to bucket-wheel excavators and trenchers. Bucket chain excavators remove material from below their plane of movement, which is useful if the pit floor is unstable or underwater.

A conveyor bridge is a piece of mining equipment used in strip mining for the removal of overburden and for dumping it on the inner spoil bank of the open-cut mine. It is used together with multibucket excavators, frequently bucket chain excavators, that remove the overburden which is moved to the bridge by connecting conveyors. Conveyor bridges are used in working horizontally layered deposits with soft overburden rock in areas where mean annual temperatures are above freezing. They are frequently used in lignite mining.

Bagger 1473 is a Type SRs 1500-series bucket-wheel excavator prototype left abandoned in a field in the municipality of Schipkau in Germany.

The Type SRs 8000 or less commonly known as the SRs 8000-class, is a family of bucket-wheel excavators known for being one of the largest terrestrial vehicles ever made by man, with Bagger 293 its - "lead vessel" - being the largest ground vehicle in history. The Type SRs 8000 classification was coined by TAKRAF to describe specifically, Bagger 293, although it is unclear if this extends to its other "sibling vehicles" within the same bulk.

The Type Es 3750 or simply the Es 3750 is a series of bucket chain excavators built by TAKRAF and used in Germany. According to TAKRAF, they boast that the Type Es 3750 is the largest bucket chain excavators in the world. Type Es 3750s are notable for being always used in conjunction with the Overburden Conveyor Bridge F60, another absurdly large land vehicle.

The Type SRs 2000 is a class of medium-sized bucket-wheel excavators built by TAKRAF. It is by far, one of the most common and recognizable BWEs built and sold by TAKRAF, with 56 Type SRs 2000s being commissioned and launched as of 2013.