Related Research Articles

Anna Laetitia Barbauld was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children's literature. A prominent member of the Blue Stockings Society and a "woman of letters" who published in multiple genres, Barbauld had a successful writing career that spanned more than half a century.

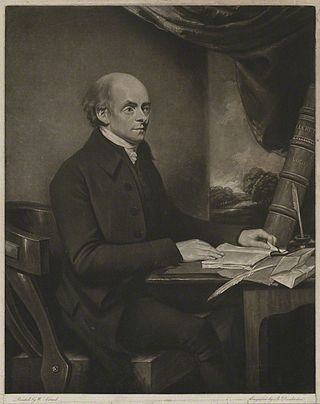

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English scholar and controversialist. He moved from being a cleric and academic, into tutoring at dissenting academies, and finally became a professional writer and publicist. In a celebrated state trial, he was imprisoned for a pamphlet critical of government policy of the French Revolutionary Wars; and died shortly after his release.

William Drennan was an Irish physician and writer who moved the formation in Belfast and Dublin of the Society of United Irishmen. He was the author of the Society's original "test" which, in the cause of representative government, committed "Irishmen of every religious persuasion" to a "brotherhood of affection". Drennan had been active in the Irish Volunteer movement and achieved renown with addresses to the public as his "fellow slaves" and to the British Viceroy urging "full and final" Catholic emancipation. After the suppression of the 1798 Rebellion, he sought to advance democratic reform through his continued journalism and through education. With other United Irish veterans, Drennan founded the Belfast [later the Royal Belfast] Academical Institution. As a poet, he is remembered for his eve-of-rebellion When Erin First Rose (1795) with its reference to Ireland as the "Emerald Isle".

John Thelwall was a radical British orator, writer, political reformer, journalist, poet, elocutionist and speech therapist.

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution from 1789 to 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which defended the House of Bourbon, the French aristocracy, and the Catholic Church in France. Because he had supported the American Patriots in their rebellion against Great Britain, Burke's views sent a shockwave through the British Isles. Many writers responded to defend the French Revolution, such as Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Alfred Cobban calls the debate that erupted "perhaps the last real discussion of the fundamentals of politics" in Britain. The themes articulated by those responding to Burke would become a central feature of the radical working-class movement in Britain in the 19th century and of Romanticism. Most Britons celebrated the storming of the Bastille in 1789 and believed that Kingdom of France should be curtailed by a more democratic form of government. However, by December 1795, after the Reign of Terror and the War of the First Coalition, few still supported the French cause.

The Monthly Repository was a British monthly Unitarian periodical which ran between 1806 and 1838. In terms of editorial policy on theology, the Repository was largely concerned with rational dissent. Considered as a political journal, it was radical, supporting a platform of: abolition of monopolies ; abolition of slavery; repeal of "taxes on knowledge"; extension of suffrage; national education; reform of the Church of England; and changes to the Poor Laws.

Stephen Lushington, generally known as Dr Lushington, was a British judge, Member of Parliament and a radical for the abolition of slavery and capital punishment. He served as Judge of the High Court of Admiralty from 1838 to 1867.

Sonnets on Eminent Characters or Sonnets on Eminent Contemporaries is an 11-part sonnet series created by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and printed in the Morning Chronicle between 1 December 1794 and 31 January 1795. Although Coleridge promised to have at least 16 poems within the series, only one addition poem, "To Lord Stanhope", was published.

Benjamin Flower was an English radical journalist and political writer, and a vocal opponent of his country's involvement in the early stages of the Napoleonic Wars.

George Cannon (1789–1854) was an English solicitor, radical activist and publisher and pornographer who also used the pseudonyms Erasmus Perkins and Philosemus.

William Burdon (1764–1818) was an English academic, mineowner and writer.

Martha Gurney (1733–1816) was an English printer, bookseller and publisher, known as an abolitionist activist.

John Tweddell (1769–1799) was an English classical scholar and traveller.

Felix Vaughan was an English barrister, known for his role as defence counsel in the treason trials of the 1790s.

The Oeconomist, full title The Oeconomist, Or, Englishman's Magazine, was an English monthly periodical at the end of the 18th century. It was published in Newcastle upon Tyne, and was edited by Thomas Bigge, in partnership with James Losh.

William Hamilton Reid was a British poet and hack writer. A supporter of radical politics turned loyalist, he is known for his 1800 pamphlet exposé The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies in this Metropolis. His later views turned again towards radicalism.

James Webbe Tobin (1767–1814) was an English abolitionist, the son of a plantation owner on Nevis. He was a political radical, and friend of leading literary men.

Thomas Mullett (1745–1814) was an English businessman and supporter of the American Revolution.

Sarah Lawrence (1780–1859) was an English educator, writer and literary editor. She ran a girls' school in Gateacre near Liverpool, and was a family friend of the Aikins of Warrington, and an associate of members of the Roscoe circle.

Peter Crompton (1765–1833) was an English physician, political radical and brewer.

References

- Timothy D. Whelan, ed. (2008). Politics, Religion and Romance: The Letters of Benjamin Flower and Eliza Gould Flower, 1794–1808. National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-1-86225-070-3.