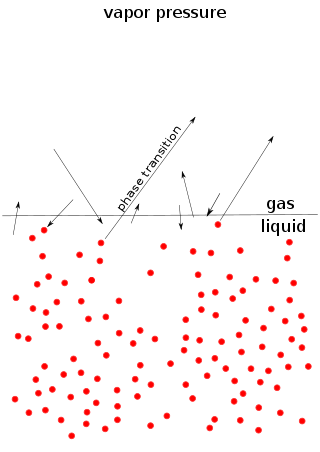

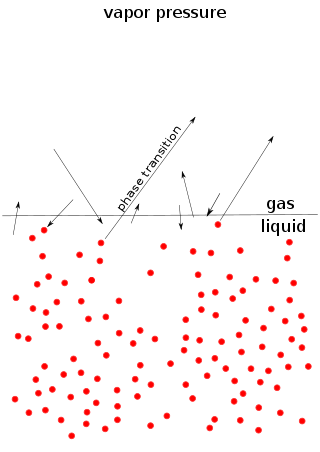

Vapor pressure or equilibrium vapor pressure is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases at a given temperature in a closed system. The equilibrium vapor pressure is an indication of a liquid's thermodynamic tendency to evaporate. It relates to the balance of particles escaping from the liquid in equilibrium with those in a coexisting vapor phase. A substance with a high vapor pressure at normal temperatures is often referred to as volatile. The pressure exhibited by vapor present above a liquid surface is known as vapor pressure. As the temperature of a liquid increases, the attractive interactions between liquid molecules become less significant in comparison to the entropy of those molecules in the gas phase, increasing the vapor pressure. Thus, liquids with strong intermolecular interactions are likely to have smaller vapor pressures, with the reverse true for weaker interactions.

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor to liquid water when in contact with a liquid or solid surface or cloud condensation nuclei within the atmosphere. When the transition happens from the gaseous phase into the solid phase directly, the change is called deposition.

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects to float on a water surface without becoming even partly submerged.

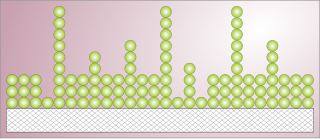

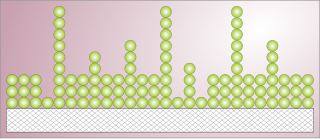

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the adsorbate on the surface of the adsorbent. This process differs from absorption, in which a fluid is dissolved by or permeates a liquid or solid. While adsorption does often precede absorption, which involves the transfer of the absorbate into the volume of the absorbent material, alternatively, adsorption is distinctly a surface phenomenon, wherein the adsorbate does not penetrate through the material surface and into the bulk of the adsorbent. The term sorption encompasses both adsorption and absorption, and desorption is the reverse of sorption.

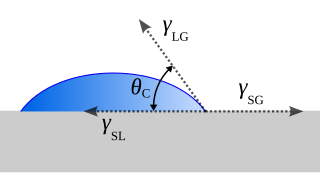

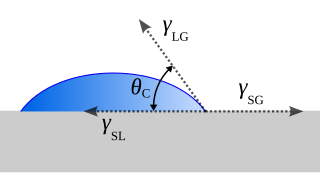

Wetting is the ability of a liquid to displace gas to maintain contact with a solid surface, resulting from intermolecular interactions when the two are brought together. This happens in presence of a gaseous phase or another liquid phase not miscible with the first one. The degree of wetting (wettability) is determined by a force balance between adhesive and cohesive forces. There are two types of wetting: non-reactive wetting and reactive wetting.

The contact angle is the angle between a liquid surface and a solid surface where they meet. More specifically, it is the angle between the surface tangent on the liquid–vapor interface and the tangent on the solid–liquid interface at their intersection. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory aims to explain the physical adsorption of gas molecules on a solid surface and serves as the basis for an important analysis technique for the measurement of the specific surface area of materials. The observations are very often referred to as physical adsorption or physisorption. In 1938, Stephen Brunauer, Paul Hugh Emmett, and Edward Teller presented their theory in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. BET theory applies to systems of multilayer adsorption that usually utilizes a probing gas (called the adsorbate) that does not react chemically with the adsorptive (the material upon which the gas attaches to) to quantify specific surface area. Nitrogen is the most commonly employed gaseous adsorbate for probing surface(s). For this reason, standard BET analysis is most often conducted at the boiling temperature of N2 (77 K). Other probing adsorbates are also utilized, albeit less often, allowing the measurement of surface area at different temperatures and measurement scales. These include argon, carbon dioxide, and water. Specific surface area is a scale-dependent property, with no single true value of specific surface area definable, and thus quantities of specific surface area determined through BET theory may depend on the adsorbate molecule utilized and its adsorption cross section.

The Ostwald–Freundlich equation governs boundaries between two phases; specifically, it relates the surface tension of the boundary to its curvature, the ambient temperature, and the vapor pressure or chemical potential in the two phases.

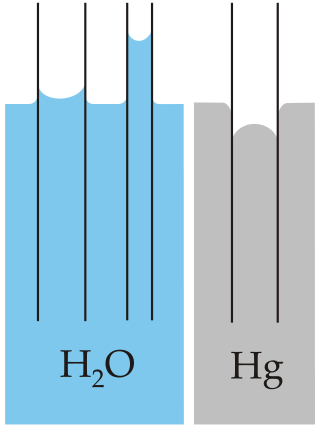

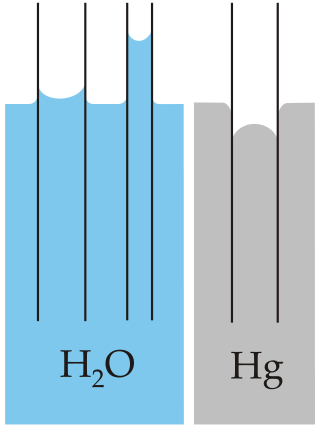

In fluid statics, capillary pressure is the pressure between two immiscible fluids in a thin tube, resulting from the interactions of forces between the fluids and solid walls of the tube. Capillary pressure can serve as both an opposing or driving force for fluid transport and is a significant property for research and industrial purposes. It is also observed in natural phenomena.

At equilibrium, the relationship between water content and equilibrium relative humidity of a material can be displayed graphically by a curve, the so-called moisture sorption isotherm. For each humidity value, a sorption isotherm indicates the corresponding water content value at a given, constant temperature. If the composition or quality of the material changes, then its sorption behaviour also changes. Because of the complexity of sorption process the isotherms cannot be determined explicitly by calculation, but must be recorded experimentally for each product.

The Kelvin equation describes the change in vapour pressure due to a curved liquid–vapor interface, such as the surface of a droplet. The vapor pressure at a convex curved surface is higher than that at a flat surface. The Kelvin equation is dependent upon thermodynamic principles and does not allude to special properties of materials. It is also used for determination of pore size distribution of a porous medium using adsorption porosimetry. The equation is named in honor of William Thomson, also known as Lord Kelvin.

The Freundlich equation or Freundlich adsorption isotherm, an adsorption isotherm, is an empirical relationship between the quantity of a gas adsorbed into a solid surface and the gas pressure. The same relationship is also applicable for the concentration of a solute adsorbed onto the surface of a solid and the concentration of the solute in the liquid phase. In 1909, Herbert Freundlich gave an expression representing the isothermal variation of adsorption of a quantity of gas adsorbed by unit mass of solid adsorbent with gas pressure. This equation is known as Freundlich adsorption isotherm or Freundlich adsorption equation. As this relationship is entirely empirical, in the case where adsorption behavior can be properly fit by isotherms with a theoretical basis, it is usually appropriate to use such isotherms instead. The Freundlich equation is also derived (non-empirically) by attributing the change in the equilibrium constant of the binding process to the heterogeneity of the surface and the variation in the heat of adsorption.

In physics, the Young–Laplace equation is an algebraic equation that describes the capillary pressure difference sustained across the interface between two static fluids, such as water and air, due to the phenomenon of surface tension or wall tension, although use of the latter is only applicable if assuming that the wall is very thin. The Young–Laplace equation relates the pressure difference to the shape of the surface or wall and it is fundamentally important in the study of static capillary surfaces. It is a statement of normal stress balance for static fluids meeting at an interface, where the interface is treated as a surface : where is the Laplace pressure, the pressure difference across the fluid interface, is the surface tension, is the unit normal pointing out of the surface, is the mean curvature, and and are the principal radii of curvature. Note that only normal stress is considered, because a static interface is possible only in the absence of tangential stress.

The capillary length or capillary constant is a length scaling factor that relates gravity and surface tension. It is a fundamental physical property that governs the behavior of menisci, and is found when body forces (gravity) and surface forces are in equilibrium.

Köhler theory describes the process in which water vapor condenses and forms liquid cloud drops, and is based on equilibrium thermodynamics. It combines the Kelvin effect, which describes the change in saturation vapor pressure due to a curved surface, and Raoult's Law, which relates the saturation vapor pressure to the solute. It is an important process in the field of cloud physics. It was initially published in 1936 by Hilding Köhler, Professor of Meteorology in the Uppsala University.

Jurin's law, or capillary rise, is the simplest analysis of capillary action—the induced motion of liquids in small channels—and states that the maximum height of a liquid in a capillary tube is inversely proportional to the tube's diameter. Capillary action is one of the most common fluid mechanical effects explored in the field of microfluidics. Jurin's law is named after James Jurin, who discovered it between 1718 and 1719. His quantitative law suggests that the maximum height of liquid in a capillary tube is inversely proportional to the tube's diameter. The difference in height between the surroundings of the tube and the inside, as well as the shape of the meniscus, are caused by capillary action. The mathematical expression of this law can be derived directly from hydrostatic principles and the Young–Laplace equation. Jurin's law allows the measurement of the surface tension of a liquid and can be used to derive the capillary length.

Thermoporometry and cryoporometry are methods for measuring porosity and pore-size distributions. A small region of solid melts at a lower temperature than the bulk solid, as given by the Gibbs–Thomson equation. Thus, if a liquid is imbibed into a porous material, and then frozen, the melting temperature will provide information on the pore-size distribution. The detection of the melting can be done by sensing the transient heat flows during phase transitions using differential scanning calorimetry – DSC thermoporometry, measuring the quantity of mobile liquid using nuclear magnetic resonance – NMR cryoporometry (NMRC) or measuring the amplitude of neutron scattering from the imbibed crystalline or liquid phases – ND cryoporometry (NDC).

The Gibbs–Thomson effect, in common physics usage, refers to variations in vapor pressure or chemical potential across a curved surface or interface. The existence of a positive interfacial energy will increase the energy required to form small particles with high curvature, and these particles will exhibit an increased vapor pressure. See Ostwald–Freundlich equation. More specifically, the Gibbs–Thomson effect refers to the observation that small crystals are in equilibrium with their liquid melt at a lower temperature than large crystals. In cases of confined geometry, such as liquids contained within porous media, this leads to a depression in the freezing point / melting point that is inversely proportional to the pore size, as given by the Gibbs–Thomson equation.

The potential theory of Polanyi, also called Polanyi adsorption potential theory, is a model of adsorption proposed by Michael Polanyi where adsorption can be measured through the equilibrium between the chemical potential of a gas near the surface and the chemical potential of the gas from a large distance away. In this model, he assumed that the attraction largely due to Van Der Waals forces of the gas to the surface is determined by the position of the gas particle from the surface, and that the gas behaves as an ideal gas until condensation where the gas exceeds its equilibrium vapor pressure. While the adsorption theory of Henry is more applicable in low pressure and BET adsorption isotherm equation is more useful at from 0.05 to 0.35 P/Po, the Polanyi potential theory has much more application at higher P/Po (~0.1–0.8).

A capillary bridge is a minimized surface of liquid or membrane created between two rigid bodies of arbitrary shape. Capillary bridges also may form between two liquids. Plateau defined a sequence of capillary shapes known as (1) nodoid with 'neck', (2) catenoid, (3) unduloid with 'neck', (4) cylinder, (5) unduloid with 'haunch' (6) sphere and (7) nodoid with 'haunch'. The presence of capillary bridge, depending on their shapes, can lead to attraction or repulsion between the solid bodies. The simplest cases of them are the axisymmetric ones. We distinguished three important classes of bridging, depending on connected bodies surface shapes: