The Great Victoria Desert is a sparsely populated desert ecoregion and interim Australian bioregion in Western Australia and South Australia.

The Murray-Sunset National Park is the second largest national park in Victoria, Australia, located in the Mallee district in the northwestern corner of the state, bordering South Australia. The 633,000-hectare (1,560,000-acre) national park is situated approximately 440 kilometres (270 mi) northwest of Melbourne and was proclaimed on 26 April 1979. It is in the northwestern corner of the state, bordering South Australia to the west and the Murray River to the north. The Sturt Highway passes through the northern part of the park, but most of the park is in the remote area between the Sturt Highway and the Mallee Highway, west of the Calder Highway.

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic watersheds – those with no outlets – in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California, Mexico. It is noted for both its arid climate and the basin and range topography that varies from the North American low point at Badwater Basin in Death Valley to the highest point of the contiguous United States, less than 100 miles (160 km) away at the summit of Mount Whitney. The region spans several physiographic divisions, biomes, ecoregions, and deserts.

An endorheic basin is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water, such as rivers or oceans, but drainage converges instead into lakes or swamps, permanent or seasonal, that equilibrate through evaporation. They are also called closed or terminal basins or internal drainage systems or basins. Endorheic regions contrast with exorheic regions. Endorheic water bodies include some of the largest lakes in the world, such as the Caspian Sea, the world's largest inland body of water.

A dry lake bed, also known as a playa, is a basin or depression that formerly contained a standing surface water body, which disappeared when evaporation processes exceeded recharge. If the floor of a dry lake is covered by deposits of alkaline compounds, it is known as an alkali flat. If covered with salt, it is known as a salt flat.

The Lake Eyre basin is a drainage basin that covers just under one-sixth of all Australia. It is the largest endorheic basin in Australia and amongst the largest in the world, covering about 1,200,000 square kilometres (463,323 sq mi), including much of inland Queensland, large portions of South Australia and the Northern Territory, and a part of western New South Wales. The basin is also one of the largest, least-developed arid zone basins with a high degree of variability anywhere. It supports about 60,000 people and a large amount of wildlife, and has no major irrigation, diversions or flood-plain developments. Low density grazing is the major land use, occupying 82% of the total land within the basin.

The Cooper Creek is one of the most famous rivers in Australia because it was the site of the death of the explorers Burke and Wills in 1861. It is sometimes known as the Barcoo River from one of its tributaries and is one of three major Queensland river systems that flow into the Lake Eyre basin. The flow of the creek depends on monsoonal rains falling months earlier and many hundreds of kilometres away in eastern Queensland. It is 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) in length.

The Sevier River is a 400-mile (640 km)-long river in the Great Basin of southwestern Utah in the United States. Originating west of Bryce Canyon National Park, the river flows north through a chain of high farming valleys and steep canyons along the west side of the Sevier Plateau, before turning southwest and terminating in the endorheic basin of Sevier Lake in the Sevier Desert. It is used extensively for irrigation along its course, with the consequence that Sevier Lake is usually dry.

The Gibson Desert is a large desert in Western Australia. and is still largely in an almost "pristine" state. It is about 155,000 square kilometres (60,000 sq mi) in size, making it the fifth largest desert in Australia, after the Great Victoria, Great Sandy, Tanami and Simpson deserts. The Gibson Desert is both an interim Australian bioregion and desert ecoregion.

The Pila Nguru, often referred to in English as the Spinifex people, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Australia, whose lands extend to the border with South Australia and to the north of the Nullarbor Plain. The centre of their homeland is in the Great Victoria Desert, at Tjuntjunjarra, some 700 kilometres (430 mi) east of Kalgoorlie, perhaps the remotest community in Australia. Their country is sometimes referred to as Spinifex country. The Pila Nguru were the last Australian people to have dropped the complete trappings of their traditional lifestyle.

Mamungari Conservation Park is a protected area located in South Australia within the southern Great Victoria Desert and northern Nullarbor Plain about 200 kilometres west of Maralinga and 450 kilometres northwest of Ceduna. It is about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north-west of Adelaide and abuts the Western Australia border

Oak Valley is the only community of Maralinga Tjarutja Aboriginal Council (AC) Local Government Area (LGA), South Australia. The population fluctuates, but a 2016 survey reported around 128 people, mostly Aboriginal. It is approximately 128 kilometres (80 mi) NNW of the original Maralinga township, and lies at the southern edge of the Great Victoria Desert. It is named for the desert oaks that populate the vicinity of the community.

The Maralinga Tjarutja, or Maralinga Tjarutja Council, is the corporation representing the traditional Anangu owners of the remote western areas of South Australia known as the Maralinga Tjarutja lands. The council was established by the Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act 1984. The area is one of the four regions of South Australia classified as an Aboriginal Council (AC) and not incorporated within a local government area.

Desert exploration is the deliberate and scientific exploration of deserts, the arid regions of the earth. It is only incidentally concerned with the culture and livelihood of native desert dwellers. People have struggled to live in deserts and the surrounding semi-arid lands for millennia. Nomads have moved their flocks and herds to wherever grazing is available, and oases have provided opportunities for a more settled way of life. Many, such as the Bushmen in the Kalahari, the Aborigines in Australia and various Indigenous peoples of the Americas, were originally hunter-gatherers. Many trade routes have been forged across deserts, especially across the Sahara Desert, and traditionally were used by caravans of camels carrying salt, gold, ivory and other goods. Large numbers of slaves were also taken northwards across the Sahara. Today, some mineral extraction also takes place in deserts, and the uninterrupted sunlight gives potential for the capture of large quantities of solar energy.

The Serpentine Lakes is a chain of salt lakes in the Great Victoria Desert of Australia. It runs for almost 100 km (62 mi) along the border between South Australia and Western Australia. When full, the lakes cover an area of 9,700 hectares (97 km2). Most of it is located in the Mamungari Conservation Park. The Anne Beadell Highway crosses the northernmost arm of the lake.

Iltur is a remote Pitjantjatjara homeland in the Great Victoria Desert of South Australia. It is also known as Coffin Hill after the rocky outcrop where it is located, and the traditional country surrounding it is known in Pitjantjatjara as Ilturnga. It is located at the southern end of the Birksgate Range, and is one of the most southerly locations on the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. It was visited by the Elder Scientific Exploring Expedition in 1881, led by the explorer David Lindsay.

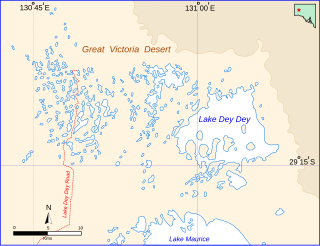

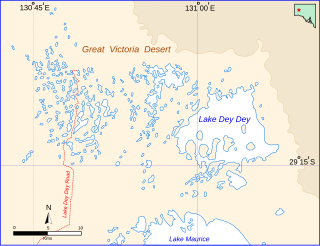

Lake Dey Dey is one of many ephemeral salt lakes located in the eastern end of the Great Victoria Desert, in the Far North region of South Australia.

The Prairie Evaporite Formation, also known as the Prairie Formation, is a geologic formation of Middle Devonian (Givetian) age that consists primarily of halite and other evaporite minerals. It is present beneath the plains of northern and eastern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan and southwestern Manitoba in Canada, and it extends into northwestern North Dakota and northeastern Montana in the United States.

The Alkali Lakes are a series of three large playas located in the Surprise Valley of northeastern California, United States. From north to south they are known as Upper, Middle and Lower Alkali Lake. Upper Alkali Lake is often known simply as Upper Lake, and Lower Alkali Lake as Lower Lake. Although mostly located in Modoc County, California, the eastern edges of Middle and Lower Lakes touch Washoe County, Nevada. The Warner Mountains are located to the west of the three lakes. The lake beds are typically flooded with shallow water in the winter but dry up during most summers.

The Raak Plain Boinka is a wilderness area in the state of Victoria, Australia. The boinka groundwater discharge complex is a shallow depression within a region of Mallee dune fields, and contains gypsum flats and salinas, pools of salty water that are mainly fed by groundwater. The distinctive flora of the boinka is largely intact and includes several threatened species.