The Province of Upper Canada was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Quebec since 1763. Upper Canada included all of modern-day Southern Ontario and all those areas of Northern Ontario in the Pays d'en Haut which had formed part of New France, essentially the watersheds of the Ottawa River or Lakes Huron and Superior, excluding any lands within the watershed of Hudson Bay. The "upper" prefix in the name reflects its geographic position along the Great Lakes, mostly above the headwaters of the Saint Lawrence River, contrasted with Lower Canada to the northeast.

The Aroostook War, or the Madawaska War, was a military and civilian-involved confrontation in 1838–1839 between the United States and the United Kingdom over the international boundary between the British colony of New Brunswick and the U.S. state of Maine. The term "war" was rhetorical; local militia units were called out but never engaged in actual combat. The event is best described as an international incident.

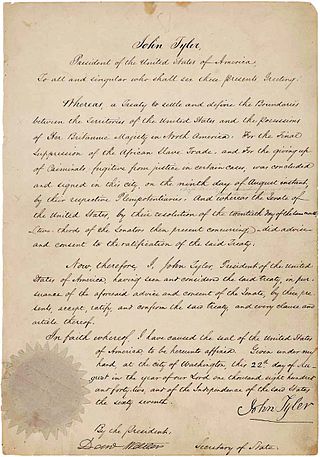

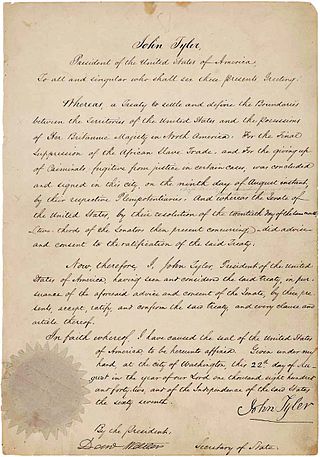

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies. Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it resolved the so-called Aroostook War. The provisions of the treaty included:

William Lyon Mackenzie was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented York County in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada and aligned with Reformers. He led the rebels in the Upper Canada Rebellion; after its defeat, he unsuccessfully rallied American support for an invasion of Upper Canada as part of the Patriot War. Although popular for criticising government officials, he failed to implement most of his policy objectives. He is one of the most recognizable Reformers of the early 19th century.

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the rebellion in Lower Canada, which started the previous month, that emboldened rebels in Upper Canada to revolt.

The Battle of Windsor was a short-lived campaign in the eastern Michigan area of the United States and the Windsor area of Upper Canada. A group of men on both sides of the border, calling themselves "Patriots", formed small militias in 1837 with the intention of seizing the Southern Ontario peninsula between the Detroit and Niagara Rivers and extending American-style government to Canada. They based groups in Michigan at Fort Gratiot, Mount Clemens, Detroit, and Gibraltar. The Patriots were defeated by British and American government forces, respectively.

The Rebellions of 1837–1838, were two armed uprisings that took place in Lower and Upper Canada in 1837 and 1838. Both rebellions were motivated by frustrations with lack of political reform. A key shared goal was responsible government, which was eventually achieved in the incidents' aftermath. The rebellions led directly to Lord Durham's Report on the Affairs of British North America and to the Act of Union 1840 which partially reformed the British provinces into a unitary system and eventually led to the British North America Act, 1867, which created the contemporary Canadian federation and its government.

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet was a Canadian political leader, land speculator and property investor, lawyer, soldier, and militia commander who served in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada twice, the Legislative Assembly for the Province of Canada once, and served as joint Premier of the Province of Canada from 1854 to 1856. MacNab was "likely the largest land speculator in Upper Canada during his time" as mentioned both in his official biography in retrospect and in 1842 by Sir Charles Bagot.

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending war shortly before that attack materializes. It is a war that preemptively 'breaks the peace' before an impending attack occurs.

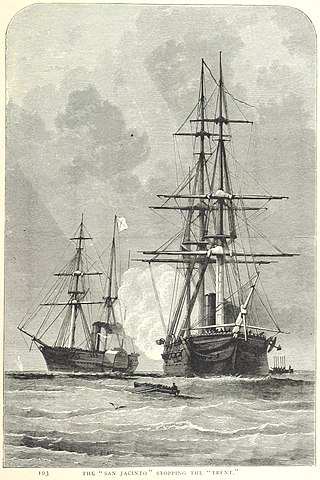

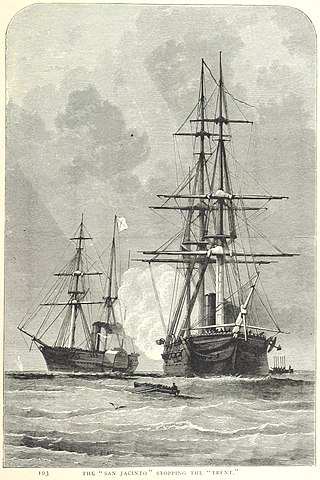

The Trent Affair was a diplomatic incident in 1861 during the American Civil War that threatened a war between the United States and the United Kingdom. The U.S. Navy captured two Confederate envoys from a British Royal Mail steamer; the British government protested vigorously. American public and elite opinion strongly supported the seizure, but it worsened the economy and was ruining relations with the world's strongest economy and strongest navy. President Abraham Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the envoys.

Queenston is a compact rural community and unincorporated place 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of Niagara Falls in the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada. It is bordered by Highway 405 to the south and the Niagara River to the east; its location at the eponymous Queenston Heights on the Niagara Escarpment led to the establishment of the Queenston Quarry in the area. Across the river and the Canada–US border is the village of Lewiston, New York. The Lewiston-Queenston Bridge links the two communities. This village is at the point where the Niagara River began eroding the Niagara Escarpment. During the ensuing 12,000 years the Falls cut an 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long gorge in the Escarpment southward to its present-day position.

The Chesapeake Affair was an international diplomatic incident that occurred during the American Civil War. On December 7, 1863, Confederate sympathizers from the British colonies Nova Scotia and New Brunswick captured the American steamer Chesapeake off the coast of Cape Cod. The expedition was planned and led by Vernon Guyon Locke (1827–1890) of Nova Scotia and John Clibbon Brain (1840–1906). When George Wade of New Brunswick killed one of the American crew, the Confederacy claimed its first fatality in New England waters.

Hugo Grotius, the 17th-century jurist and father of public international law, stated in his 1625 magnum opus The Law of War and Peace that "Most Men assign three Just Causes of War, Defence, the Recovery of what's our own, and Punishment."

The Republic of Canada was a government proclaimed by William Lyon Mackenzie on December 5, 1837. The self-proclaimed government was established on Navy Island in the Niagara River in the latter days of the Upper Canada Rebellion.

The Creole mutiny, sometimes called the Creole case, was a slave revolt aboard the American slave ship Creole in November 1841, when the brig was seized by the 128 slaves who were aboard the ship when it reached Nassau in the British colony of the Bahamas where slavery was abolished. The brig was transporting enslaved people as part of the coastwise slave trade in the American South. It has been described as the "most successful slave revolt in US history". Two died in the revolt, an enslaved person and a member of the crew.

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and December 1838. This so-called war was not a conflict between nations; it was a war of ideas fought by like-minded people against British forces, with the British eventually allying with the US government against the Patriots.

Alexander McLeod (1796–1871) was a Scottish-Canadian who served as sheriff in Niagara, Ontario. After the Upper Canada Rebellion, he boasted that he had partaken in the 1837 Caroline Affair, the sinking of an American steamboat that had been supplying William Lyon Mackenzie's rebels with arms. Three years later, he was arrested by the United States and charged with the murder of the sailor killed in the attack, but his incarceration infuriated Canada and Great Britain, which demanded his repatriation in the strongest terms; arguing that any action taken against the Caroline had been taken under orders, and the responsibility lay with the Crown, not McLeod himself.

Bill Johnston was a Canadian-American smuggler, river pirate, and War of 1812 privateer. Born in Canada, Johnston was accused of spying in 1812 and he joined the American side of the war and lived the rest of his life in the United States.

The Caroline test is a 19th-century formulation of customary international law, reaffirmed by the Nuremberg Tribunal after World War II, which said that the necessity for preemptive self-defense must be "instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation." The test takes its name from the Caroline affair.

The Great Lakes Patrol was carried out by American naval forces, beginning in 1844, mainly to suppress criminal activity and to protect the maritime border with Canada. A small force of United States Navy, Coast Guard, and Revenue Service ships served in the Great Lakes throughout these operations. Through the decades, they were involved in several incidents with pirates and rebels.