Related Research Articles

Gaius Valerius Catullus, often referred to simply as Catullus, was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His surviving works are still read widely and continue to influence poetry and other forms of art.

In poetry, a hendecasyllable is a line of eleven syllables. The term may refer to several different poetic meters, the older of which are quantitative and used chiefly in classical poetry, and the newer of which are syllabic or accentual-syllabic and used in medieval and modern poetry.

The Priapeia is a collection of eighty anonymous short Latin poems in various meters on subjects pertaining to the phallic god Priapus. They are believed to date from the 1st century AD or the beginning of the 2nd century. A traditional theory about their origin is that they are an anthology of poems written by various authors on the same subject. However, it has recently been argued that the 80 poems are in fact the work of a single author, presenting a kind of biography of Priapus from his vigorous youth to his impotence in old age.

Lesbia was the literary pseudonym used by the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus to refer to his lover. Lesbia is traditionally identified with Clodia, the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer and sister of Publius Clodius Pulcher; her conduct and motives are maligned in Cicero's extant speech Pro Caelio, delivered in 56 BC.

Catullus 51 is a poem by Roman love poet Gaius Valerius Catullus (c. 84 – c. 54 BC). It is an adaptation of one of Sappho's fragmentary lyric poems, Sappho 31. Catullus replaces Sappho's beloved with his own beloved Lesbia. Unlike the majority of Catullus' poems, the meter of this poem is the sapphic meter. This meter is more musical, seeing as Sappho mainly sang her poetry.

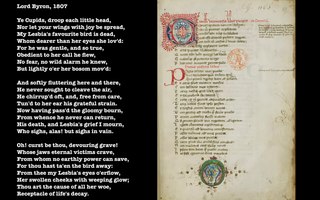

Catullus 3 is a poem by Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus that laments the death of a pet sparrow (passer) for which an unnamed girl (puella), possibly Catullus' lover Lesbia, had an affection. Written in hendecasyllabic meter, it is considered to be one of the most famous of Latin poems.

Catullus 85 is a poem by the Roman poet Catullus for his lover Lesbia. Its declaration of conflicting feelings, "I hate and I love", is renowned for its drama, force and brevity. The meter of the poem is the elegiac couplet.

Catullus 6 is a Latin poem of seventeen lines in Phalaecean hendecasyllabic metre by the Roman poet Catullus.

Catullus 8 is a Latin poem of nineteen lines in choliambic metre by the Roman poet Catullus, known by its incipit, Miser Catulle.

Catullus 10 is a Latin poem of thirty-four lines in Phalaecean metre by the Roman poet Catullus.

The poetry of Gaius Valerius Catullus was written towards the end of the Roman Republic. It describes the lifestyle of the poet and his friends, as well as, most famously, his love for the woman he calls Lesbia.

Catullus 16 or Carmen 16 is a poem by Gaius Valerius Catullus. The poem, written in a hendecasyllabic (11-syllable) meter, was considered to be so sexually explicit following its rediscovery in the following centuries that a full English translation was not published until the 20th century. The first line, Pēdīcābo ego vōs et irrumābō, sometimes used as a title, has been called "one of the filthiest expressions ever written in Latin—or in any other language".

Catullus 36 is a Latin poem of twenty lines in Phalaecean metre by the Roman poet Catullus.

Catullus 86 is a Latin poem of six lines in elegiac couplets by the Roman poet Catullus.

Catullus 63 is a Latin poem of 93 lines in galliambic metre by the Roman poet Catullus.

Catullus 42 is a Latin poem of twenty-four lines in Phalaecean metre by the Roman poet Catullus.

Catullus 58b is a poem written by the Roman poet Catullus. In this poem he tells that even if he had the power of mythological figures, such as Perseus and Pegagus, still he would he grow weary of searching for his friend, the Camerius of Catullus 55. The meter is hendecasyllabic, the same as Catullus 55. There is debate as to the provenance of the poem. Some scholars have tried to tie it to Catullus 55, though the only connection may be that the writer chose to cut it out of 55. Others believe that it was an earlier draft of the poem. Still others feel it was a separate poem entirely and that it stands well as such. A discarded view is that Catullus did not write 58B.

Leonard Charles Smithers was a London bookseller and publisher associated with the Decadent movement.

Latin prosody is the study of Latin poetry and its laws of meter. The following article provides an overview of those laws as practised by Latin poets in the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire, with verses by Catullus, Horace, Virgil and Ovid as models. Except for the early Saturnian poetry, which may have been accentual, Latin poets borrowed all their verse forms from the Greeks, despite significant differences between the two languages.