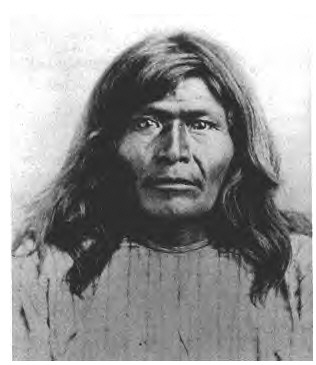

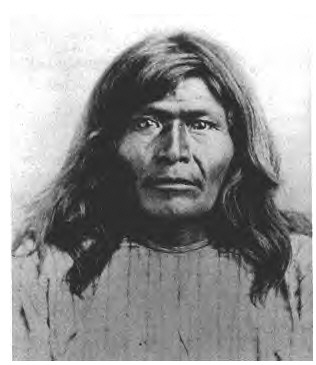

Victorio was a warrior and chief of the Warm Springs band of the Tchihendeh division of the central Apaches in what is now the American states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua.

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexican–American War in 1846, the United States annexed conflicted territory from Mexico which was the home of both settlers and Apache tribes. Conflicts continued as American settlers came into traditional Apache lands to raise livestock and crops and to mine minerals.

The Tonto Apache Tribe of Arizona or Tonto Apache is a federally recognized tribe of Western Apache people located in northwestern Gila County, Arizona. The term "Tonto" is also used for their dialect, one of the three dialects of the Western Apache language, a member of Southern Athabaskan language family. The Tonto Apache Reservation is the smallest land base reservation in the state of Arizona.

The 10th Cavalry Regiment is a unit of the United States Army. Formed as a segregated African-American unit, the 10th Cavalry was one of the original "Buffalo Soldier" regiments in the post–Civil War Regular Army. It served in combat during the Indian Wars in the western United States, the Spanish–American War in Cuba, Philippine–American War and Mexican Revolution. The regiment was trained as a combat unit but later relegated to non-combat duty and served in that capacity in World War II until its deactivation in 1944.

Native Americans have made up an integral part of U.S. military conflicts since America's beginning. Colonists recruited Indian allies during such instances as the Pequot War from 1634–1638, the Revolutionary War, as well as in War of 1812. Native Americans also fought on both sides during the American Civil War, as well as military missions abroad including the most notable, the Codetalkers who served in World War II. The Scouts were active in the American West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Including those who accompanied General John J. Pershing in 1916 on his expedition to Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Indian Scouts were officially deactivated in 1947 when their last member retired from the Army at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. For many Indians it was an important form of interaction with European-American culture and their first major encounter with the Whites' way of thinking and doing things.

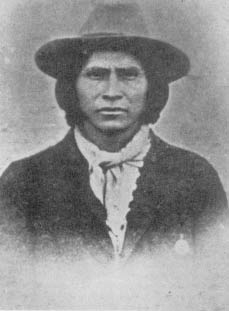

The Apache Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts. Most of their service was during the Apache Wars, between 1849 and 1886, though the last scout retired in 1947. The Apache scouts were the eyes and ears of the United States military and sometimes the cultural translators for the various Apache bands and the Americans. Apache scouts also served in the Navajo War, the Yavapai War, the Mexican Border War and they saw stateside duty during World War II. There has been a great deal written about Apache scouts, both as part of United States Army reports from the field and more colorful accounts written after the events by non-Apaches in newspapers and books. Men such as Al Sieber and Tom Horn were sometimes the commanding officers of small groups of Apache Scouts. As was the custom in the United States military, scouts were generally enlisted with Anglo nicknames or single names. Many Apache Scouts received citations for bravery.

William Giles Harding Carter was a US Cavalry officer who served during the American Civil War, Spanish–American War and World War I. He also took part in the Indian Wars seeing extensive service against the Apache and Comanche in Arizona being awarded the Medal of Honor against the Apache during the Comanche Campaign on August 30, 1881.

The Battle of Big Dry Wash was fought on July 17, 1882, between troops of the United States Army's 3rd Cavalry Regiment and 6th Cavalry Regiment and warriors of the White Mountain Apache tribe.The location of the battle was called "Big Dry Wash" in Major Evans' official report, but later maps called the location "Big Dry Fork", which is how it is cited in the four Medal of Honor citations that resulted from the battle.

Louis Henry Carpenter was a United States Army brigadier general and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in the American Indian Wars.

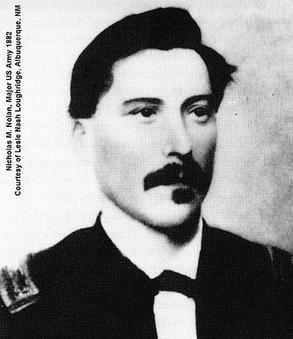

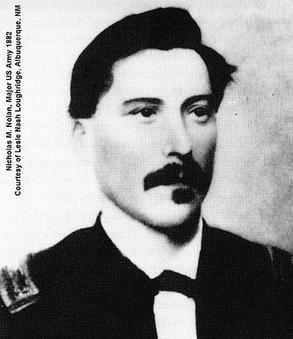

Nicholas Merritt Nolan was a United States Army major. An Irish immigrant, he began his military career in New York on December 9, 1852, with the 4th Artillery, and subsequently served in New York's 2nd Dragoons. He enlisted as a private and rose through the ranks becoming a first sergeant. He was commissioned an officer in late 1862 in the Regular Army, while serving with the 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment during the American Civil War. He participated in 16 campaigns with the 6th and most of its battles. He was slightly wounded at the Battle of Fairfield and seriously wounded at the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House. He was brevetted twice and noted at least twice for gallantry during combat. He was slightly wounded when captured at the end of March 1865, and was later paroled. After the Civil War, he served with the 10th U.S. Cavalry, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, for 14 years. Nolan is also noted for his pluses and minuses during the Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877 that made headlines in the Eastern United States. He was the commanding officer of Henry O. Flipper in 1878, the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point. He commanded several frontier forts before his untimely death in 1883.

First Lieutenant Charles Bare Gatewood was an American soldier / officer born in Woodstock, Virginia. He was raised in nearby Harrisonburg, Virginia, where his father ran a printing press. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Army and assigned to the Army's in the 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment after graduating from the United States Military Academy on the upper Hudson River, at West Point, New York. Upon assignment to the American Southwest territories, Gatewood led platoons of Apache and Navajo scouts against renegades during the Apache Wars of the 1860s, 1870s and into the 1880s phase of the ongoing century-long American Indian Wars. In 1886, he played a key role in ending the Geronimo Campaign, by pursuing, meeting with and persuading Geronimo to cross back over the American-Mexican international border, from where the renegade guerrilla leader was holed up in the mountains of northern Mexico, convincing him to eventually surrender to him and commanding General Nelson A. Miles (1839-1925), of the Army.

John Nihill was an Irish-born soldier in the U.S. Army who served with the 5th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian Wars. A participant in the Apache Wars, he received the Medal of Honor for bravery when he single-handedly fought off four Apache warriors in the Whetstone Mountains of Arizona on July 13, 1872. At the time of his death, he was the only enlisted man to be admitted as a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

Henry Newman was a German-born soldier in the U.S. Army who served with the 5th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian Wars. In the Apache Wars, he was one of three men who received the Medal of Honor for gallantry against a hostile band of Apache Indians in the Whetstone Mountains of Arizona on July 13, 1872.

The Crawford affair was a battle fought between Mexico and the United States in January 1886 during the Geronimo Campaign. Captain Emmet Crawford was commanding a company of Apache scouts, sixty miles southeast of Nacori Chico in Sonora, when his camp was attacked by Mexican Army militiamen. In the action, Crawford was shot and later died; his death nearly started a war between the United States and Mexico.

Victorio's War, or the Victorio Campaign, was an armed conflict between the Apache followers of Chief Victorio, the United States, and Mexico beginning in September 1879. Faced with arrest and forcible relocation from his homeland in New Mexico to San Carlos Indian Reservation in southeastern Arizona, Victorio led a guerrilla war across southern New Mexico, west Texas and northern Mexico. Victorio fought many battles and skirmishes with the United States Army and raided several settlements until the Mexican Army killed him and most of his warriors in October 1880 in the Battle of Tres Castillos. After Victorio's death, his lieutenant Nana led a raid in 1881.

The Kelvin Grade massacre was an incident that occurred on November 2, 1889 when a group of nine imprisoned Apache escaped from police custody during a prisoner transfer near the town of Globe, Arizona. The escape resulted in the deaths of two sheriffs and triggered one of the largest manhunts in Arizona history. Veterans of the Apache Wars scoured the Arizona frontier for nearly a year in search of the fugitives, by the end of which all were caught or killed except for the famous Indian scout known as the Apache Kid.

The post-1887 Apache Wars period of the Apache Wars refers to campaigns by the United States and Mexico against the Apaches.

The raid on Bear Valley was an armed conflict that occurred in 1886 during Geronimo's War. In late April, a band of Chiricahua Apaches attacked settlements in Santa Cruz County, Arizona over the course of two days. The Apaches raided four cattle ranches in or around Bear Valley, leaving four settlers dead, including a woman and her baby. They also captured a young girl, who was found dead several days after the event, and stole or destroyed a large amount of private property. When the United States Army learned of the attack, an expedition was launched to pursue the hostiles. In May, two small skirmishes were fought just across the international border in Sonora, Mexico but both times the Apaches were able to escape capture.

The Apache Campaign of 1896 was the final United States Army operation against Apaches who were raiding and not living in a reservation. It began in April after Apache raiders killed three white American settlers in the Arizona Territory. The Apaches were pursued by the army, which caught up with them in the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico, Sonora and Chihuahua. There were only two important encounters during the campaign and, because both of them occurred in the remote Four Corners region, it is unknown if they took place on American or Mexican soil.

Clay Beauford was an American army officer, scout and frontiersman. An ex-Confederate soldier in his youth, he later enlisted in the U.S. Army and served with the 5th U.S. Cavalry during the Indian Wars against the Plains Indians from 1869 to 1873. He acted as a guide for Lieutenant Colonel George Crook in his "winter campaign" against the Apaches and received the Medal of Honor for his conduct.