Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical genomes, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction; this reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate is known as parthenogenesis. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the process of creating cloned organisms of cells and of DNA fragments.

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissue. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibilities of human cloning have raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass laws regarding human cloning.

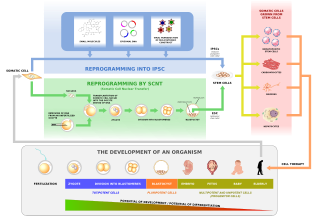

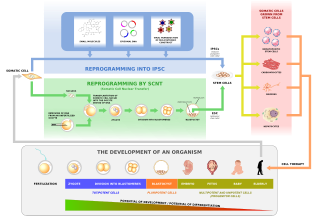

In genetics and developmental biology, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a laboratory strategy for creating a viable embryo from a body cell and an egg cell. The technique consists of taking an denucleated oocyte and implanting a donor nucleus from a somatic (body) cell. It is used in both therapeutic and reproductive cloning. In 1996, Dolly the sheep became famous for being the first successful case of the reproductive cloning of a mammal. In January 2018, a team of scientists in Shanghai announced the successful cloning of two female crab-eating macaques from foetal nuclei.

Leon Richard Kass is an American physician, scientist, educator, and public intellectual. Kass is best known as a proponent of liberal arts education via the "Great Books," as a critic of human cloning, life extension, euthanasia and embryo research, and for his tenure as chairman of the President's Council on Bioethics from 2001 to 2005. Although Kass is often referred to as a bioethicist, he eschews the term and refers to himself as "an old-fashioned humanist. A humanist is concerned broadly with all aspects of human life, not just the ethical."

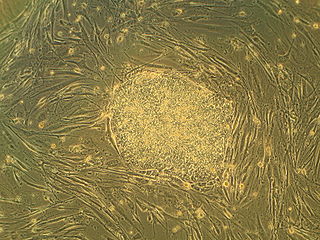

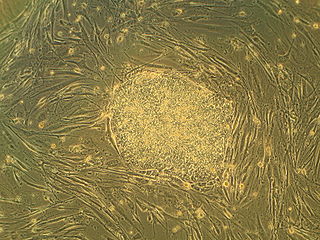

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre-implantation embryo. Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist of 50–150 cells. Isolating the inner cell mass (embryoblast) using immunosurgery results in destruction of the blastocyst, a process which raises ethical issues, including whether or not embryos at the pre-implantation stage have the same moral considerations as embryos in the post-implantation stage of development.

A designer baby is a baby whose genetic makeup has been selected or altered, often to exclude a particular gene or to remove genes associated with disease. This process usually involves analysing a wide range of human embryos to identify genes associated with particular diseases and characteristics, and selecting embryos that have the desired genetic makeup; a process known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Screening for single genes is commonly practiced, and polygenic screening is offered by a few companies. Other methods by which a baby's genetic information can be altered involve directly editing the genome before birth, which is not routinely performed and only one instance of this is known to have occurred as of 2019, where Chinese twins Lulu and Nana were edited as embryos, causing widespread criticism.

In religion and philosophy, ensoulment is the moment at which a human or other being gains a soul. Some belief systems maintain that a soul is newly created within a developing child and others, especially in religions that believe in reincarnation, that the soul is pre-existing and added at a particular stage of development.

The stem cell controversy concerns the ethics of research involving the development and use of human embryos. Most commonly, this controversy focuses on embryonic stem cells. Not all stem cell research involves human embryos. For example, adult stem cells, amniotic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells do not involve creating, using, or destroying human embryos, and thus are minimally, if at all, controversial. Many less controversial sources of acquiring stem cells include using cells from the umbilical cord, breast milk, and bone marrow, which are not pluripotent.

Stem cell research policy varies significantly throughout the world. There are overlapping jurisdictions of international organizations, nations, and states or provinces. Some government policies determine what is allowed versus prohibited, whereas others outline what research can be publicly financed. Of course, all practices not prohibited are implicitly permitted. Some organizations have issued recommended guidelines for how stem cell research is to be conducted.

In bioethics, the ethics of cloning concerns the ethical positions on the practice and possibilities of cloning, especially of humans. While many of these views are religious in origin, some of the questions raised are faced by secular perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, as human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

Samuel H. Wood is a scientist and fertility specialist. In 2008, he became the first man to clone himself, donating his own DNA via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) to produce mature human embryos that were his clones.

Christianity and abortion have a long and complex history. There is a general consensus that the texts of the Bible are "ambiguous" on the subject of abortion. While it does not contain explicit support or opposition, there have been several passages that have been interpreted to indicate both. Today, Christian denominations hold widely variant stances.

The Ten Commandments are series of religious and moral imperatives that are recognized as a moral foundation in several of the Abrahamic religions, including the Catholic Church. As described in the Old Testament books Exodus and Deuteronomy, the Commandments form part of a covenant offered by God to the Israelites to free them from the spiritual slavery of sin. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church—the official exposition of the Catholic Church's Christian beliefs—the Commandments are considered essential for spiritual good health and growth, and serve as the basis for Catholic social teaching. A review of the Commandments is one of the most common types of examination of conscience used by Catholics before receiving the sacrament of Penance.

Stem cell laws are the law rules, and policy governance concerning the sources, research, and uses in treatment of stem cells in humans. These laws have been the source of much controversy and vary significantly by country. In the European Union, stem cell research using the human embryo is permitted in Sweden, Spain, Finland, Belgium, Greece, Britain, Denmark and the Netherlands; however, it is illegal in Germany, Austria, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal. The issue has similarly divided the United States, with several states enforcing a complete ban and others giving support. Elsewhere, Japan, India, Iran, Israel, South Korea, China, and Australia are supportive. However, New Zealand, most of Africa, and most of South America are restrictive.

Stem cell laws and policy in the United States have had a complicated legal and political history.

The laws and policies regarding stem cell research in the People's Republic of China are relatively relaxed in comparison to that of other nations. The reason for this is due to different traditional and cultural views in relation to that of the West.

Religious response to assisted reproductive technology deals with the new challenges for traditional social and religious communities raised by modern assisted reproductive technology. Because many religious communities have strong opinions and religious legislation regarding marriage, sex and reproduction, modern fertility technology has forced religions to respond.

The multilateral foreign policy of the Holy See is particularly active on some issues, such as human rights, disarmament, and economic and social development, which are dealt with in international fora.

The Human Reproductive Cloning Act 2001 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom "to prohibit the placing in a woman of a human embryo which has been created otherwise than by fertilisation". The act received Royal Assent on 4 December 2001.

The Hwang affair, or Hwang scandal, or Hwanggate, is a case of scientific misconduct and ethical issues surrounding a South Korean biologist, Hwang Woo-suk, who claimed to have created the first human embryonic stem cells by cloning in 2004. Hwang and his research team at the Seoul National University reported in the journal Science that they successfully developed a somatic cell nuclear transfer method with which they made the stem cells. In 2005, they published again in Science the successful cloning of 11 person-specific stem cells using 185 human eggs. The research was hailed as "a ground-breaking paper" in science. Hwang was elevated as "the pride of Korea", "national hero" [of Korea], and a "supreme scientist", to international praise and fame. Recognitions and honours immediately followed, including South Korea's Presidential Award in Science and Technology, and Time magazine listing him among the "People Who Mattered 2004" and the most influential people "The 2004 Time 100".