George Bannatyne (1545–1608), a native of Angus, Scotland, was an Edinburgh merchant and burgess. He was the seventh of twenty-three children, including Catherine Bannatyne, born of James Bannatyne of Kirktown of Newtyle in Forfarshire and Katherine Tailefer. He is most famous as a collector of Scottish poems. He compiled an anthology of Scots poetry while in isolation during a plague in 1568. His work extended to eight hundred folio pages, divided into five parts. The anthology includes works from Scottish Chaucerians as well as many anonymous writers.

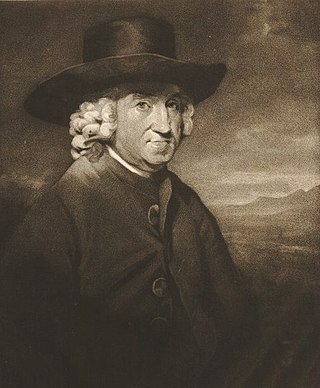

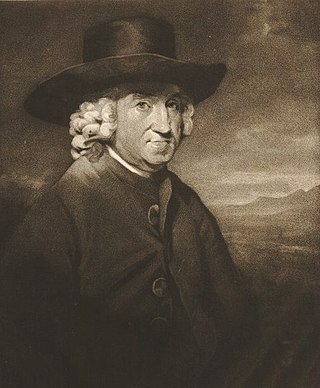

Allan Ramsay was a Scottish poet, playwright, publisher, librarian and impresario of early Enlightenment Edinburgh. Ramsay's influence extended to England, foreshadowing the reaction that followed the publication of Percy's Reliques. He was on close terms with the leading men of letters in Scotland and England. He corresponded with William Hamilton of Bangour, William Somervile, John Gay and Alexander Pope.

Robert Fergusson was a Scottish poet. After formal education at the University of St Andrews, Fergusson led a bohemian life in Edinburgh, the city of his birth, then at the height of intellectual and cultural ferment as part of the Scottish Enlightenment. Many of his extant poems were printed from 1771 onwards in Walter Ruddiman's Weekly Magazine, and a collected works was first published early in 1773. Despite a short life, his career was highly influential, especially through its impact on Robert Burns. He wrote both Scottish English and the Scots language, and it is his vivid and masterly writing in the latter leid for which he is principally acclaimed.

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

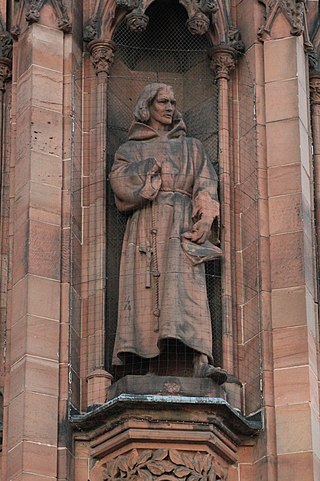

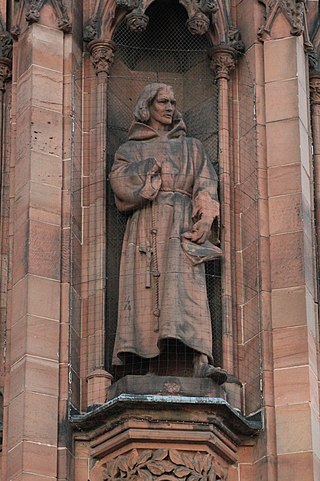

William Dunbar was a Scottish makar, or court poet, active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. He was closely associated with the court of King James IV and produced a large body of work in Scots distinguished by its great variation in themes and literary styles. He was probably a native of East Lothian, as assumed from a satirical reference in The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie. His surname is also spelt Dumbar.

William Tytler WS FRSE (1711–1792) was a Scottish lawyer, known as a historical writer. He wrote An Inquiry into the Evidence against Mary Queen of Scots, against the views of William Robertson. He discovered the manuscript the "Kingis Quhair", a poem of James I of Scotland. In 1783 he was one of the joint founders of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Alexander Arbuthnot (1538–1583) was a Scottish ecclesiastic poet, "an eminent divine, and zealous promoter of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland". He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in both 1573 and 1577.

Alexander Scott was a Scottish Court poet. He is believed to have spent most of his time in or near Edinburgh. Thirty-six short poems are attributed to him, including Ane New Yeir Gift to Quene Mary, The Rondel of Love, and a satire, Justing at the Drum. His poems are included in the Bannatyne Manuscript (1568) complied by George Bannatyne. According to an older view, "he has great variety of metre, and is graceful and musical, but his satirical pieces are often extremely coarse".

The Eneados is a translation into Middle Scots of Virgil's Latin Aeneid, completed by the poet and clergyman Gavin Douglas in 1513.

The Bannatyne Manuscript is an anthology of literature compiled in Scotland in the sixteenth century. It is an important source for the Scots poetry of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The manuscript contains texts of the poems of the great makars, many anonymous Scots pieces and works by medieval English poets.

William Stewart was a Scottish poet working in the first half of the 16th century.

Scottish literature in the Middle Ages is literature written in Scotland, or by Scottish writers, between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century, until the establishment of the Renaissance in the late fifteenth century and early sixteenth century. It includes literature written in Brythonic, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French and Latin.

Literature in early modern Scotland is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers between the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution in mid-eighteenth century. By the beginning of this era Gaelic had been in geographical decline for three centuries and had begun to be a second-class language, confined to the Highlands and Islands, but the traditions of Bard poetry in the Classical Gaelic literary language continued to survive. Middle Scots became the language of both the nobility and the majority population. The establishment of a printing press in 1507 made it easier to disseminate Scottish literature and was probably aimed at bolstering Scottish national identity.

Poetry of Scotland includes all forms of verse written in Brythonic, Latin, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French, English and Esperanto and any language in which poetry has been written within the boundaries of modern Scotland, or by Scottish people.

Scottish literature in the eighteenth century is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers in the eighteenth century. It includes literature written in English, Scottish Gaelic and Scots, in forms including poetry, drama and novels. After the Union in 1707 Scottish literature developed a distinct national identity. Allan Ramsay led a "vernacular revival", the trend for pastoral poetry and developed the Habbie stanza. He was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English who included William Hamilton of Gilbertfield, Robert Crawford, Alexander Ross, William Hamilton of Bangour, Alison Rutherford Cockburn, and James Thomson. The eighteenth century was also a period of innovation in Gaelic vernacular poetry. Major figures included Rob Donn Mackay, Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, Uillean Ross and Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair, who helped inspire a new form of nature poetry. James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by Ossian. Robert Burns is widely regarded as the national poet.

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (1375). Some ballads may date back to the thirteenth century, but were not recorded until the eighteenth century. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun's verse Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland and Blind Harry's The Wallace. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem The Kingis Quair. Writers such as William Dunbar, Robert Henryson, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. The first complete surviving work is John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s. The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid.

Marie Maitland was a Scottish writer and poet, a member of the Maitland family of Lethington and Thirlestane Castle, and later Lady Haltoun. Her first name is sometimes written as "Mary".

George Clapperton was a Scottish nobleman, vernacular poet, and a patron of the Bannatyne Manuscript living in the 1500s.

Ane New Yeir Gift to Quene Mary is a poem written by Alexander Scott (1520?-1582/1583) in 1562, as a New Year's gift to Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary had recently returned to Scotland from France following the death of her first husband, Francois II of France (d.1560). The poem was written in an effort to placate Mary's displeasure following her official reception into the City of Edinburgh organised by its burgh council in August 1561, at which Protestant imagery was highlighted. As a committed Catholic Mary had taken offence.

James Carmichael (1542/3–1628) was the Church of Scotland minister and an author known for a Latin grammar published at Cambridge in September 1587 and for his work revising the Second Book of Discipline and the Acts of Assembly. In 1584, Carmichael was forced to seek shelter in England along with the Melvilles and others. Andrew Melville called him "the profound dreamer." Robert Wodrow said that "a great strain of both piety and strong learning runs through his letters and papers." Dr. Laing says there is every probability that " The Booke of the Universall Kirk " was compiled by Carmichael. The James Carmichaell collection of proverbs in Scots was published by Edinburgh University in 1957 which includes some proverbs also collected by David Ferguson.