A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (elements), usually arranged along a common axis. Lenses are made from materials such as glass or plastic and are ground, polished, or molded to the required shape. A lens can focus light to form an image, unlike a prism, which refracts light without focusing. Devices that similarly focus or disperse waves and radiation other than visible light are also called "lenses", such as microwave lenses, electron lenses, acoustic lenses, or explosive lenses.

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light. Light is a type of electromagnetic radiation, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation such as X-rays, microwaves, and radio waves exhibit similar properties.

A parabolicreflector is a reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface generated by a parabola revolving around its axis. The parabolic reflector transforms an incoming plane wave travelling along the axis into a spherical wave converging toward the focus. Conversely, a spherical wave generated by a point source placed in the focus is reflected into a plane wave propagating as a collimated beam along the axis.

Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behavior and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behavior of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light. Because light is an electromagnetic wave, other forms of electromagnetic radiation such as X-rays, microwaves, and radio waves exhibit similar properties.

A synchrotron light source is a source of electromagnetic radiation (EM) usually produced by a storage ring, for scientific and technical purposes. First observed in synchrotrons, synchrotron light is now produced by storage rings and other specialized particle accelerators, typically accelerating electrons. Once the high-energy electron beam has been generated, it is directed into auxiliary components such as bending magnets and insertion devices in storage rings and free electron lasers. These supply the strong magnetic fields perpendicular to the beam that are needed to stimulate the high energy electrons to emit photons.

The Newtonian telescope, also called the Newtonian reflector or just a Newtonian, is a type of reflecting telescope invented by the English scientist Sir Isaac Newton, using a concave primary mirror and a flat diagonal secondary mirror. Newton's first reflecting telescope was completed in 1668 and is the earliest known functional reflecting telescope. The Newtonian telescope's simple design has made it very popular with amateur telescope makers.

In accelerator physics, a beamline refers to the trajectory of the beam of particles, including the overall construction of the path segment along a specific path of an accelerator facility. This part is either

A monochromator is an optical device that transmits a mechanically selectable narrow band of wavelengths of light or other radiation chosen from a wider range of wavelengths available at the input. The name is from Greek mono- 'single' chroma 'colour' and Latin -ator 'denoting an agent'.

An optical cavity, resonating cavity or optical resonator is an arrangement of mirrors or other optical elements that confines light waves similarly to how a cavity resonator confines microwaves. Optical cavities are a major component of lasers, surrounding the gain medium and providing feedback of the laser light. They are also used in optical parametric oscillators and some interferometers. Light confined in the cavity reflects multiple times, producing modes with certain resonance frequencies. Modes can be decomposed into longitudinal modes that differ only in frequency and transverse modes that have different intensity patterns across the cross section of the beam. Many types of optical cavities produce standing wave modes.

A collimator is a device which narrows a beam of particles or waves. To narrow can mean either to cause the directions of motion to become more aligned in a specific direction, or to cause the spatial cross section of the beam to become smaller.

A light beam or beam of light is a directional projection of light energy radiating from a light source. Sunlight forms a light beam when filtered through media such as clouds, foliage, or windows. To artificially produce a light beam, a lamp and a parabolic reflector is used in many lighting devices such as spotlights, car headlights, PAR Cans, and LED housings. Light from certain types of laser has the smallest possible beam divergence.

The shearing interferometer is an extremely simple means to observe interference and to use this phenomenon to test the collimation of light beams, especially from laser sources which have a coherence length which is usually significantly longer than the thickness of the shear plate so that the basic condition for interference is fulfilled.

X-ray optics is the branch of optics dealing with X-rays, rather than visible light. It deals with focusing and other ways of manipulating the X-ray beams for research techniques such as X-ray diffraction, X-ray crystallography, X-ray fluorescence, small-angle X-ray scattering, X-ray microscopy, X-ray phase-contrast imaging, and X-ray astronomy.

An autocollimator is an optical instrument for non-contact measurement of angles. They are typically used to align components and measure deflections in optical or mechanical systems. An autocollimator works by projecting an image onto a target mirror and measuring the deflection of the returned image against a scale, either visually or by means of an electronic detector. A visual autocollimator can measure angles as small as 1 arcsecond, while an electronic autocollimator can have up to 100 times more resolution.

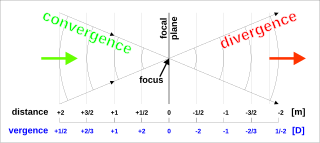

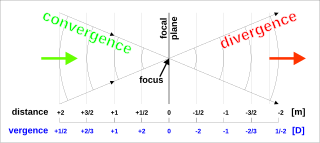

In optics, vergence is the angle formed by rays of light that are not perfectly parallel to one another. Rays that move closer to the optical axis as they propagate are said to be converging, while rays that move away from the axis are diverging. These imaginary rays are always perpendicular to the wavefront of the light, thus the vergence of the light is directly related to the radii of curvature of the wavefronts. A convex lens or concave mirror will cause parallel rays to focus, converging toward a point. Beyond that focal point, the rays diverge. Conversely, a concave lens or convex mirror will cause parallel rays to diverge.

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental research in particle physics. Accelerators are also used as synchrotron light sources for the study of condensed matter physics. Smaller particle accelerators are used in a wide variety of applications, including particle therapy for oncological purposes, radioisotope production for medical diagnostics, ion implanters for the manufacture of semiconductors, and accelerator mass spectrometers for measurements of rare isotopes such as radiocarbon.

A conoscopic interference pattern or interference figure is a pattern of birefringent colours crossed by dark bands, which can be produced using a geological petrographic microscope for the purposes of mineral identification and investigation of mineral optical and chemical properties. The figures are produced by optical interference when diverging light rays travel through an optically non-isotropic substance – that is, one in which the substance's refractive index varies in different directions within it. The figure can be thought of as a "map" of how the birefringence of a mineral would vary with viewing angle away from perpendicular to the slide, where the central colour is the birefringence seen looking straight down, and the colours further from the centre equivalent to viewing the mineral at ever increasing angles from perpendicular. The dark bands correspond to positions where optical extinction would be seen. In other words, the interference figure presents all possible birefringence colours for the mineral at once.

A reflector sight or reflex sight is an optical sight that allows the user to look through a partially reflecting glass element and see an illuminated projection of an aiming point or some other image superimposed on the field of view. These sights work on the simple optical principle that anything at the focus of a lens or curved mirror will appear to be sitting in front of the viewer at infinity. Reflector sights employ some form of "reflector" to allow the viewer to see the infinity image and the field of view at the same time, either by bouncing the image created by lens off a slanted glass plate, or by using a mostly clear curved glass reflector that images the reticle while the viewer looks through the reflector. Since the reticle is at infinity, it stays in alignment with the device to which the sight is attached regardless of the viewer's eye position, removing most of the parallax and other sighting errors found in simple sighting devices.

A Cheshire eyepiece or Cheshire collimator is a simple tool that helps aligning the optical axes of the mirrors or lenses of a telescope, a process called collimation. It consists of a peephole to be inserted into the focuser in place of the eyepiece. Through a lateral opening, ambient light falls on the brightly painted oblique back of the peephole. Images of this bright surface are reflected by the mirrors or lenses of the telescope and can thus be seen by a person peering through the hole. A Cheshire eyepiece contains no lenses or other polished optical surfaces.