Related Research Articles

Lugh or Lug is a figure in Irish mythology. A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of supernatural beings, Lugh is portrayed as a warrior, a king, a master craftsman and a saviour. He is associated with skill and mastery in multiple disciplines, including the arts. Lugh also has associations with oaths, truth, and the law, and therefore with rightful kingship. Lugh is linked with the harvest festival of Lughnasadh, which bears his name. His most common epithets are Lámfada and Samildánach. This has sometimes been anglicised as "Lew of the Long Hand".

In Irish mythology, the Badb, or in modern Irish Badhbh —also meaning "crow"—is a war goddess who takes the form of a crow, and is thus sometimes known as Badb Catha. She is known to cause fear and confusion among soldiers to move the tide of battle to her favoured side. Badb may also appear prior to a battle to foreshadow the extent of the carnage to come, or to predict the death of a notable person. She would sometimes do this through wailing cries, leading to comparisons with the bean-sídhe (banshee).

Macha was a sovereignty goddess of ancient Ireland associated with the province of Ulster, particularly the sites of Navan Fort and Armagh, which are named after her. Several figures called Macha appear in Irish mythology and folklore, all believed to derive from the same goddess. She is said to be one of three sisters known as 'the three Morrígna'. Like other sovereignty goddesses, Macha is associated with the land, fertility, kingship, war and horses.

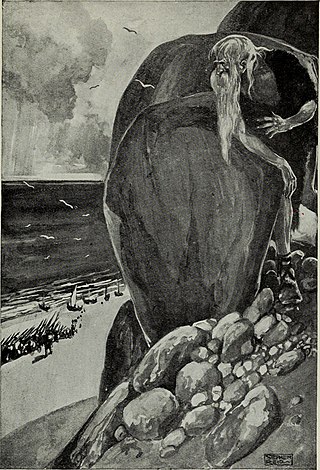

In Irish mythology, Balor or Balar was a leader of the Fomorians, a group of malevolent supernatural beings, and considered the most formidable. He is often described as a giant with a large eye that wreaks destruction when opened. Balor takes part in the Battle of Mag Tuired, and is primarily known from the tale in which he is killed by his grandson Lugh of the Tuatha Dé Danann. He has been interpreted as a personification of the scorching sun, and has also been likened to figures from other mythologies, such as the Welsh Ysbaddaden and the Greek Cyclops.

In Irish mythology, Caitlín was the wife of Balor of the Fomorians and, by him, the mother of Ethniu. She was also a prophetess and warned Balor of his impending defeat by the Tuatha Dé Danann in the second battle of Magh Tuiredh. During that battle she wounded the Dagda with a projectile weapon. She was also known by the nickname Cethlenn of the Crooked Teeth.

In Irish mythology, Credne or Creidhne was the goldsmith of the Tuatha Dé Danann, but he also worked with bronze and brass. He and his brothers Goibniu and Luchtaine were known as the Trí Dée Dána, the three gods of art, who forged the weapons which the Tuatha Dé used to battle the Fomorians.

The Fomorians or Fomori are a supernatural race in Irish mythology, who are often portrayed as hostile and monstrous beings. Originally they were said to come from under the sea or the earth. Later, they were portrayed as sea raiders and giants. They are enemies of Ireland's first settlers and opponents of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the other supernatural race in Irish mythology; although some members of the two races have offspring. The Tuath Dé defeat the Fomorians in the Battle of Mag Tuired. This has been likened to other Indo-European myths of a war between gods, such as the Æsir and Vanir in Norse mythology, the Olympians and Titans in Greek mythology, and the Devas and Asuras in Indian mythology.

Nemed or Nimeth is a character in medieval Irish legend. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn, he was the leader of the third group of people to settle in Ireland: the Muintir Nemid, Clann Nemid or "Nemedians". They arrived thirty years after the Muintir Partholóin, their predecessors, had died out. Nemed eventually dies of plague and his people are oppressed by the Fomorians. They rise up against the Fomorians, attacking their tower out at sea, but most are killed and the survivors leave Ireland. Their descendants become the Fir Bolg.

In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg are the fourth group of people to settle in Ireland. They are descended from the Muintir Nemid, an earlier group who abandoned Ireland and went to different parts of Europe. Those who went to Greece became the Fir Bolg and eventually return to Ireland, after it had been uninhabited for many years. After ruling it for some time and dividing the island into provinces, they are overthrown by the invading Tuatha Dé Danann.

Ogma is a god from Irish and Scottish mythology. A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, he is often considered a deity and may be related to the Gallic god Ogmios. According to the Ogam Tract, he is the inventor of Ogham, the script in which Irish Gaelic was first written.

In Irish mythology, Ethniu in modern spelling, is the daughter of the Fomorian leader Balor, and the mother of Lugh. She is also referred to as Ethliu.

Partholón is a character in medieval Irish Christian pseudohistory, said to have led one of the first groups to settle in Ireland. His name comes from the Biblical name Bartholomaeus (Bartholomew), and may be borrowed from a character in the Christian pseudohistories of Saints Jerome and Isidore of Seville.

Lebor Gabála Érenn is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language intended to be a history of Ireland and the Irish from the creation of the world to the Middle Ages. There are a number of versions, the earliest of which was compiled by an anonymous writer in the 11th century. It synthesised narratives that had been developing over the foregoing centuries. The Lebor Gabála tells of Ireland being "taken" (settled) by six groups of people: the people of Cessair, the people of Partholón, the people of Nemed, the Fir Bolg, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the Milesians. The first four groups are wiped out or forced to abandon the island; the fifth group represents Ireland's pagan gods, while the final group represents the Irish people.

The Mythological Cycle is a conventional grouping within Irish mythology. It consists of tales and poems about the god-like Tuatha Dé Danann, who are based on Ireland's pagan deities, and other mythical races such as the Fomorians and the Fir Bolg. It is one of the four main story 'cycles' of early Irish myth and legend, along with the Ulster Cycle, the Fianna Cycle and the Cycles of the Kings. The name "Mythological Cycle" seems to have gained currency with Arbois de Jubainville c. 1881–1883. James MacKillop says the term is now "somewhat awkward", and John T. Koch notes it is "potentially misleading, in that the narratives in question represent only a small part of extant Irish mythology". He prefers T Ó Cathasaigh's name, Cycle of the Gods. Important works in the cycle are the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Cath Maige Tuired, the Aided Chlainne Lir and Tochmarc Étaíne.

Delbáeth or Delbáed was one of several figures from Irish mythology who are often confused due to the repetition of the name in the mythological genealogies.

In Irish mythology, Cichol or Cíocal Gricenchos is the earliest-mentioned leader of the Fomorians. His epithet, Gricenchos or Grigenchosach, is obscure. Macalister translates it as "clapperleg"; Comyn as "of withered feet". O'Donovan leaves it untranslated.

Eochaid Faebar Glas, son of Conmáel, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. His epithet means "blue-green sharp edge". According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn, Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn and the Annals of the Four Masters, he came to power after killing the joint High King, Cermna Finn, in battle at Dún Cermna, and Cermna's brother and colleague Sobairce was killed by Eochaid Menn of the Fomorians. He killed Smirgoll, grandson of Tigernmas, in the battle of Druimm Liatháin. He ruled for twenty years, until he was killed by Smirgoll's son Fiacha Labrainne in the battle of Carman. The Lebor Gabála synchronises his reign with that of Piritiades in Assyria. Keating's chronology dates his reign to 1115–1095 BC, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 1493–1473 BC.

Mag Itha, Magh Ithe, or Magh Iotha was, according to Irish mythology, the site of the first battle fought in Ireland. Medieval sources estimated that the battle had taken place between 2668 BCE and 2580 BCE. The opposing sides comprising the Fomorians, led by Cichol Gricenchos, and the followers of Partholón.

In medieval Irish and Scottish legend, Goídel Glas is the creator of the Goidelic languages and eponymous ancestor of the Gaels. The tradition can be traced to the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn. A Scottish variant is recorded by John of Fordun.

In Irish mythology, Cian or Cían, nicknamed Scal Balb, was the son of Dian Cecht, the physician of the Tuatha Dé Danann, and best known as the father of Lugh Lamhfada. Cían's brothers were Cu, Cethen, and Miach.

References

- ↑ MacKillop, James (2004). A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Conand, Conann, Connan…. Oxford University Press. p. 490. ISBN 9780198609674 . Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ de Jubainville, Henry Arbois (1903). The Irish Mythological Cycle and Celtic Mythology. Hodges and Figgis. p. 64.

- ↑ Macalister (1941) LGE, ¶242–243 pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Macalister (1941) LGE, ¶242–243 pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Macalister (1941) LGE, ¶244 pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Macalister (1941), p. 117.

- ↑ Morris (1927) , p. 51, note 9

- ↑ Morris (1927), pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Macalister (1941) , p. 118: "comes as near to carrying conviction as such a paper well can do".

Bibliography

- Macalister, R.A.S., ed. (1941), "Section VII: Invasion of the Tuatha De Danann", Lebor gabála Érenn, Part IV Introduction pp. 115–119. ¶242–¶ pp. 122–125

- Morris, Henry (30 June 1927), "Where Was Tor Inis, the Island Fortress of the Fomorians?", The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, 17: 47–58, JSTOR 25513429