Related Research Articles

The Doge of Venice was the highest role of authority within the Republic of Venice. The word Doge derives from the Latin Dux, meaning "leader," originally referring to any military leader, becoming in the Late Roman Empire the title for a leader of an expeditionary force formed by detachments from the frontier army, separate from, but subject to, the governor of a province, authorized to conduct operations beyond provincial boundaries.

The Republic of Venice, traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 by Paolo Lucio Anafesto, over the course of its 1,100 years of history it established itself as one of the major European commercial and naval powers. Initially extended in the Dogado area, during its history it annexed a large part of Northeast Italy, Istria, Dalmatia, the coasts of present-day Montenegro and Albania as well as numerous islands in the Adriatic and eastern Ionian seas. At the height of its expansion, between the 13th and 16th centuries, it also governed the Peloponnese, Crete and Cyprus, most of the Greek islands, as well as several cities and ports in the eastern Mediterranean.

Pietro Loredan was a Venetian nobleman of the Loredan family and a distinguished military commander both on sea and on land. He fought against the Ottomans, winning the Battle of Gallipoli (1416), played a leading role in the conquest of Dalmatia in 1411–1420, and participated in several campaigns against Venice's Italian rivals, Genoa and Milan, to secure Venice's mainland domains (Terraferma). He also held a number of senior political positions as Avogador de Comùn, ducal councillor, and governor of Zara, Friuli, and Brescia, and was honoured with the position of Procurator of St Mark's in 1425. In 1423, he contended for the position of Doge of Venice, but lost to his bitter rival Francesco Foscari; their rivalry was such that when Loredan died, Foscari was suspected of having poisoned him.

Orso II Participazio was the eighteenth doge of the Republic of Venice, by tradition, from 912 to 932.

The Contarini is one of the founding families of Venice and one of the oldest families of the Italian Nobility. In total eight Doges to the Republic of Venice emerged from this family, as well as 44 Procurators of San Marco, numerous ambassadors, diplomats and other notables. Among the ruling families of the republic, they held the most seats in the Great Council of Venice from the period before the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio when Councillors were elected annually to the end of the republic in 1797. The Contarini claimed to be of Roman origin through their patrilineal descendance of the Aurelii Cottae, a branch of the Roman family Aurelia, and traditionally trace their lineage back to Gaius Aurelius Cotta, consul of the Roman Republic in 252 BC and 248 BC.

The House of Orseolo was a powerful Venetian noble family descended from Orso Ipato and his son Teodato Ipato, the first Doges of Venice. Four members of the Orseolo family became Doges, Commander of the Venetian fleet, and King of Hungary. They reconstructed St Mark's Basilica and the Doge's Palace after the revolution.

A doge was an elected lord and head of state in several Italian city-states, notably Venice and Genoa, during the medieval and Renaissance periods. Such states are referred to as "crowned republics".

Orso Ipato was, by tradition, the third Doge of Venice (726–737) and the first historically known. During his eleven-year reign, he brought great change to the Venetian navy, aided in the recapture of Ravenna from Lombard invaders, and cultivated harmonious relations with the Byzantine Empire. He was murdered in 737 during a civil conflict.

Orso I Participazio, also known as Orso I Badoer, was Doge of Venice from 864 until 881. He was, according to tradition, the fourteenth doge, though historically he is only the twelfth.

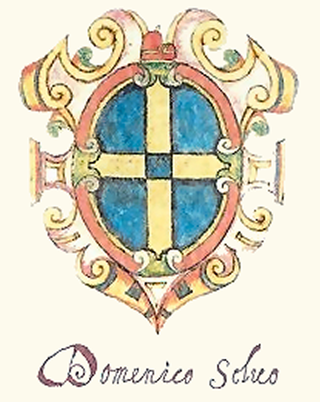

Domenico Selvo was the 31st Doge of Venice, serving from 1071 to 1084. During his reign as Doge, his domestic policies, the alliances that he forged, and the battles that the Venetian military won and lost laid the foundations for much of the subsequent foreign and domestic policy of the Republic of Venice. He avoided confrontations with the Byzantine Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Roman Catholic Church at a time in European history when conflict threatened to upset the balance of power. At the same time, he forged new agreements with the major nations that would set up a long period of prosperity for the Republic of Venice. Through his military alliance with the Byzantine Empire, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos awarded Venice economic favors with the declaration of a golden bull that would allow for the development of the republic's international trade over the next few centuries.

Otto Orseolo was the Doge of Venice from 1008 to 1026. He was the third son of Doge Pietro II of the House of Orseolo, and Maria Candiano, whom he succeeded at the age of sixteen, becoming the youngest doge in Venetian history.

Jacopo Tiepolo, also known as Giacomo Tiepolo, was Doge of Venice from 1229 to 1249. He had previously served as the first Venetian Duke of Crete, and two terms as Podestà of Constantinople, twice as governor of Treviso, and three times as ambassador to the Holy See. His dogate was marked by major domestic reforms, including the codification of civil law and the establishment of the Venetian Senate, but also against a mounting conflict with Emperor Frederick II, which broke into open war from 1237 to 1245.

Pietro Gradenigo was the 49th Doge of Venice, reigning from 1289 to his death.

This article presents a detailed timeline of the history of the Republic of Venice from its legendary foundation to its collapse under the efforts of Napoleon.

The Great Council or Major Council was a political organ of the Republic of Venice between 1172 and 1797. It was the chief political assembly, responsible for electing many of the other political offices and the senior councils that ran the Republic, passing laws, and exercising judicial oversight. Following the lockout of 1297, its membership was established on hereditary right, exclusive to the patrician families enrolled in the Golden Book of the Venetian nobility.

The Council of Forty, also known as the Quarantia, was one of the highest constitutional bodies of the Republic of Venice, with both legal and political functions as the supreme court.

The Commune of Venice is the title with which the government of the city of Venice and its Republic was designated from 1143. The municipality, similar to other medieval municipalities, was based on the popular power of the assembly, called Concio in Venice. It represented the patriciate of the city with a system of assemblies including the Great Council, Minor Council, Senate and the Council of Forty.

The Great Council Lockout refers to the constitutional process, started with the 1297 Ordinance, by means of which membership of the Great Council of Venice became hereditary. Since it was the Great Council that had the right to elect the Doge, the 1297 Ordinance marked a relevant change in the constitution of the Republic. This resulted in the exclusion of minor aristocrats and plebeians from participating in the government of the Republic. Although formerly provisional, the Ordinance later became a permanent Act, and since that time it was disregarded only at times of political or financial crisis.

The Minor Council or Ducal Council was one of the main constitutional bodies of the Republic of Venice, and served both as advisors and partners to the Doge of Venice, sharing and limiting his authority.

The Venetian patriciate was one of the three social bodies into which the society of the Republic of Venice was divided, together with citizens and foreigners. Patrizio was the noble title of the members of the aristocracy ruling the city of Venice and the Republic. The title was abbreviated, in front of the name, by the initials N.H., together with the feminine variant N.D.. Holding the title of a Venetian patrician was a great honour and many European kings and princes, as well as foreign noble families, are known to have asked for and obtained the prestigious title.

References

- Diehl, Charles: La Repubblica di Venezia, Newton & Compton editori, Roma, 2004. ISBN 8854100226