Related Research Articles

The Lateran Treaty was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman question. The treaty and associated pacts were named after the Lateran Palace where they were signed on 11 February 1929, and the Italian parliament ratified them on 7 June 1929. The treaty recognised Vatican City as an independent state under the sovereignty of the Holy See. The Italian government also agreed to give the Roman Catholic Church financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States. In 1948, the Lateran Treaty was recognized in the Constitution of Italy as regulating the relations between the state and the Catholic Church. The treaty was significantly revised in 1984, ending the status of Catholicism as the sole state religion.

Pope Pius XI, born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was the Bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to 10 February 1939. He also became the first sovereign of the Vatican City State upon its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929. He remained head of the Catholic Church until his death in February 1939. His papal motto was "Pax Christi in Regno Christi", translated as "The Peace of Christ in the Reign of Christ".

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between the First French Republic and the Holy See, signed by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII on 15 July 1801 in Paris. It remained in effect until 1905, except in Alsace–Lorraine, where it remains in force. It sought national reconciliation between the French Revolution and Catholics and solidified the Roman Catholic Church as the majority church of France, with most of its civil status restored. This resolved the hostility of devout French Catholics against the revolutionary state. It did not restore the vast Church lands and endowments that had been seized during the Revolution and sold off. Catholic clergy returned from exile, or from hiding, and resumed their traditional positions in their traditional churches. Very few parishes continued to employ the priests who had accepted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of the revolutionary regime. While the Concordat restored much power to the papacy, the balance of church-state relations tilted firmly in Bonaparte's favour. He selected the bishops and supervised church finances.

The relations between the Catholic Church and the state have been constantly evolving with various forms of government, some of them controversial in retrospect. In its history, the Church has had to deal with various concepts and systems of governance, from the Roman Empire to the medieval divine right of kings, from nineteenth- and twentieth-century concepts of democracy and pluralism to the appearance of left- and right-wing dictatorial regimes. The Second Vatican Council's decree Dignitatis humanae stated that religious freedom is a civil right that should be recognized in constitutional law.

A concordat is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both, i.e. the recognition and privileges of the Catholic Church in a particular country and with secular matters that affect church interests.

The Reichskonkordat is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII, on behalf of Pope Pius XI and Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen on behalf of President Paul von Hindenburg and the German government. It was ratified 10 September 1933 and it remains in force to this day. The treaty guarantees the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. When bishops take office, Article 16 states they are required to take an oath of loyalty to the Governor or President of the German Reich established according to the constitution. The treaty also requires all clergy to abstain from working in and for political parties. Nazi breaches of the agreement began almost as soon as it had been signed and intensified afterwards, leading to protest from the Church, including in the 1937 Mit brennender Sorge encyclical of Pope Pius XI. The Nazis planned to eliminate the Church's influence by restricting its organizations to purely religious activities.

The French Catholic Church, or Catholic Church in France is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in communion with the Pope in Rome. Established in the 2nd century in unbroken communion with the bishop of Rome, it was sometimes called the "eldest daughter of the church".

Pietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

Vehementer Nos was a papal encyclical promulgated by Pope Pius X on 11 February 1906. He denounced the French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State enacted two months earlier. He condemned its unilateral abrogation of the Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon I and Pope Pius VII that had granted the Catholic Church a distinctive status and established a working relationship between the French government and the Holy See. The title of the document is taken from its opening words in Latin, which mean "We with vehemence".

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. The Catholic Church's views and teachings have evolved over its history and have at times been significant political influences within nations.

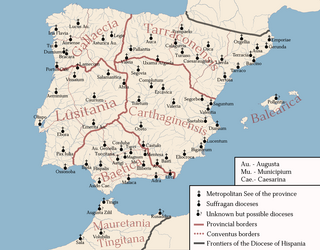

The Spanish Catholic Church, or Catholic Church in Spain, is part of the Catholic Church under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome, and the Spanish Episcopal Conference.

The Padroado was an arrangement between the Holy See and the Kingdom of Portugal and later the Portuguese Republic, through a series of concordats by which the Holy See delegated the administration of the local churches and granted some theocratic privileges to Portuguese monarchs.

Francisco de Asís Vidal y Barraquer was a Spanish Catalan cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Tarragona from 1919 until his death; he was elevated to the rank of cardinal in 1921.

Holy See–France relations are very ancient and have existed since the 5th century. They have been durable to the extent that France is sometimes called the eldest daughter of the Church.

The Catholic Church in Spain has a long history, starting in the 1st century. It is the largest religion in Spain, with 58.6% of Spaniards identifying as Catholic.

The Concordat of 1851 was a concordat between the Spanish government of Queen Isabella II and the Vatican. It was negotiated in response to the policies of the anticlerical Liberal government, which had forced her mother out as regent in 1841. Although the concordat was signed on 16 March 1851, its terms were not implemented until 1855.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

Formal diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the current Federal Republic of Germany date to the 1951 and the end of the Allied occupation. Historically the Vatican has carried out foreign relations through nuncios, beginning with the Apostolic Nuncio to Cologne and the Apostolic Nuncio to Austria. Following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the Congress of Vienna, an Apostolic Nuncio to Bavaria replaced that of Cologne and that mission remained in Munich through several governments. From 1920 the Bavarian mission existed alongside the Apostolic Nuncio to Germany in Berlin, with which it was merged in 1934.

Foreign relations between Pope Pius XI and Spain were very tense, especially because they occurred within the context of the Spanish Civil War and the period of troubles preceding it.

The Concordat of 1854 was an international treaty between the president of the Republic of Guatemala - General Captain Rafael Carrera - and the Holy See, which was signed in 1852 and ratified by both parties in 1854. Through this, Guatemala gave the education of Guatemalan people to regular orders Catholic Church, committed to respect ecclesiastical property and monasteries, imposed mandatory tithing and allowed the bishops to censor what was published in the country; in return, Guatemala received dispensations for the members of the army, allowed those who had acquired the properties that the Liberals had expropriated the Church in 1829 to keep those properties, perceived taxes generated by the properties of the Church, and had the right to judge certain crimes committed by clergy under Guatemalan law. The concordat was designed by Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol and reestablished the relationship between Church and State in Guatemala. It was in force until the fall of the conservative government of Marshal Vicente Cerna y Cerna

References

- ↑ Affairs, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World. "Spanish Concordat of March 16, 1851". berkleycenter.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Solsten, Eric; Meditz, Sandra W., eds. (1990). Spain: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 44, 111. OCLC 44200005.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ "Franco's wartime convention (1941)", Concordat Watch

- ↑ "Franco's concordat (1953) : Text", Concordat Watch

- ↑ "Spanish Concordat of 1953, Articles 1, 2, 24, 26, 31", Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, Georgetown University

- ↑ "News Headlines". Catholic Culture. 8 November 2011.

- ↑ Barbadillo, Pedro Fernández (2014-05-16). "Qué pensaba Juan XXIII de Franco". Libertad Digital (in European Spanish).

- ↑ "Modifications to Franco's concordat (1976)", Concordat Watch

- ↑ "The four 1979 concordats", Concordat Watch