The pleural cavity, or pleural space, is the potential space between the pleurae of the pleural sac that surrounds each lung. A small amount of serous pleural fluid is maintained in the pleural cavity to enable lubrication between the membranes, and also to create a pressure gradient.

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong inelastic connective tissue, and an inner layer made of serous membrane. It encloses the pericardial cavity, which contains pericardial fluid, and defines the middle mediastinum. It separates the heart from interference of other structures, protects it against infection and blunt trauma, and lubricates the heart's movements.

The thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm, is a sheet of internal skeletal muscle in humans and other mammals that extends across the bottom of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm is the most important muscle of respiration, and separates the thoracic cavity, containing the heart and lungs, from the abdominal cavity: as the diaphragm contracts, the volume of the thoracic cavity increases, creating a negative pressure there, which draws air into the lungs. Its high oxygen consumption is noted by the many mitochondria and capillaries present; more than in any other skeletal muscle.

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, fever, or weight loss, depending on the underlying cause. Pleurisy can be caused by a variety of conditions, including viral or bacterial infections, autoimmune disorders, and pulmonary embolism.

A pleural effusion is accumulation of excessive fluid in the pleural space, the potential space that surrounds each lung. Under normal conditions, pleural fluid is secreted by the parietal pleural capillaries at a rate of 0.6 millilitre per kilogram weight per hour, and is cleared by lymphatic absorption leaving behind only 5–15 millilitres of fluid, which helps to maintain a functional vacuum between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Excess fluid within the pleural space can impair inspiration by upsetting the functional vacuum and hydrostatically increasing the resistance against lung expansion, resulting in a fully or partially collapsed lung.

Radiology (X-rays) is used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Abnormalities on chest radiographs may be suggestive of, but are never diagnostic of TB, but can be used to rule out pulmonary TB.

A thoracotomy is a surgical procedure to gain access into the pleural space of the chest. It is performed by surgeons to gain access to the thoracic organs, most commonly the heart, the lungs, or the esophagus, or for access to the thoracic aorta or the anterior spine. A thoracotomy is the first step in thoracic surgeries including lobectomy or pneumonectomy for lung cancer or to gain thoracic access in major trauma.

The mediastinum is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is a region that contains vital organs and structures within the thorax, namely the heart and its vessels, the esophagus, the trachea, the vagus, phrenic and cardiac nerves, the thoracic duct, the thymus and the lymph nodes of the central chest.

A chest radiograph, chest X-ray (CXR), or chest film is a projection radiograph of the chest used to diagnose conditions affecting the chest, its contents, and nearby structures. Chest radiographs are the most common film taken in medicine.

A hemothorax is an accumulation of blood within the pleural cavity. The symptoms of a hemothorax may include chest pain and difficulty breathing, while the clinical signs may include reduced breath sounds on the affected side and a rapid heart rate. Hemothoraces are usually caused by an injury, but they may occur spontaneously due to cancer invading the pleural cavity, as a result of a blood clotting disorder, as an unusual manifestation of endometriosis, in response to pneumothorax, or rarely in association with other conditions.

A chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation of chyle, a type of lipid-rich lymph, in the pleural space surrounding the lung. The lymphatic vessels of the digestive system normally return lipids absorbed from the small bowel via the thoracic duct, which ascends behind the esophagus to drain into the left brachiocephalic vein. If normal thoracic duct drainage is disrupted, either due to obstruction or rupture, chyle can leak and accumulate within the negative-pressured pleural space. In people on a normal diet, this fluid collection can sometimes be identified by its turbid, milky white appearance, since chyle contains emulsified triglycerides.

A respiratory examination, or lung examination, is performed as part of a physical examination, in response to respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, or chest pain, and is often carried out with a cardiac examination.

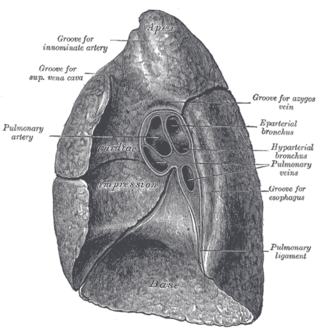

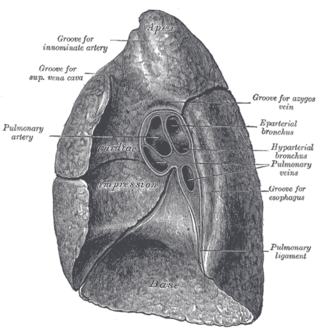

The root of the lung is a group of structures that emerge at the hilum of each lung, just above the middle of the mediastinal surface and behind the cardiac impression of the lung. It is nearer to the back than the front. The root of the lung is connected by the structures that form it to the heart and the trachea. The rib cage is separated from the lung by a two-layered membranous coating, the pleura. The hilum is the large triangular depression where the connection between the parietal pleura and the visceral pleura is made, and this marks the meeting point between the mediastinum and the pleural cavities.

In anatomy, a potential space is an inappropriate term used to describe the small space between two adjacent structures that are normally in contact one another. Examples are the pleural, the peritoneal and pericardial spaces. In other words, they are like an almost empty plastic bag that has not been opened or a balloon that has not been inflated. The pleural space, between the visceral and parietal pleura of the lung, is a potential space. Though it only contains a small amount of fluid normally, it can sometimes accumulate fluid or air that widens the space. The pericardial space is another potential space that may fill with fluid (effusion) in certain disease states.

The costomediastinal recess is a potential space at the border of the mediastinal pleura and the costal pleura. It assists lung expansion during deep inspiration, although its role is not as significant as the costodiaphragmatic recess, which has a greater volume. The lung expands into the costomediastinal recess even during shallow inspiration. The costomediastinal recess is most obvious in the cardiac notch of the left lung.

Fibrothorax is a medical condition characterised by severe scarring (fibrosis) and fusion of the layers of the pleural space surrounding the lungs resulting in decreased movement of the lung and ribcage. The main symptom of fibrothorax is shortness of breath. There also may be recurrent fluid collections surrounding the lungs. Fibrothorax may occur as a complication of many diseases, including infection of the pleural space known as an empyema or bleeding into the pleural space known as a haemothorax.

A subpulmonic effusion is excess fluid that collects at the base of the lung, in the space between the pleura and diaphragm. It is a type of pleural effusion in which the fluid collects in this particular space but can be "layered out" with decubitus chest radiographs. There is minimal nature of costophrenic angle blunting usually found with larger pleural effusions. The occult nature of the effusion can be suspected indirectly on radiograph by elevation of the right diaphragmatic border with a lateral peak and medial flattening. The presence of the gastric bubble on the left with an abnormalagm of more than 2 cm can also suggest the diagnosis. Lateral decubitus views, with the patient lying on their side, can confirm the effusion as it will layer along the lateral chest wall.

Tumor-like disorders of the lung pleura are a group of conditions that on initial radiological studies might be confused with malignant lesions. Radiologists must be aware of these conditions in order to avoid misdiagnosing patients. Examples of such lesions are: pleural plaques, thoracic splenosis, catamenial pneumothorax, pleural pseudotumor, diffuse pleural thickening, diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis and Erdheim–Chester disease.

The pleurae are the two flattened closed sacs filled with pleural fluid, each ensheathing each lung and lining their surrounding tissues, locally appearing as two opposing layers of serous membrane separating the lungs from the mediastinum, the inside surfaces of the surrounding chest walls and the diaphragm. Although wrapped onto itself resulting in an apparent double layer, each lung is surrounded by a single, continuous pleural membrane.

Mediastinal shift is an abnormal movement of the mediastinal structures toward one side of the chest cavity. A shift indicates a severe imbalance of pressures inside the chest. Mediastinal shifts are generally caused by increased lung volume, decreased lung volume, or abnormalities in the pleural space. Additionally, masses inside the mediastinum or musculoskeletal abnormalities can also lead to abnormal mediastinal arrangement. Typically, these shifts are observed on x-ray but also on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). On chest x-ray, tracheal deviation, or movement of the trachea away from its midline position can be used as a sign of a shift. Other structures, like the heart, can also be used as reference points. Below are examples of pathologies that can cause a mediastinal shift and their appearance.