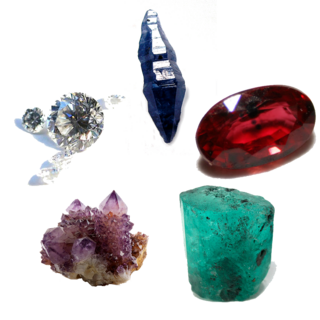

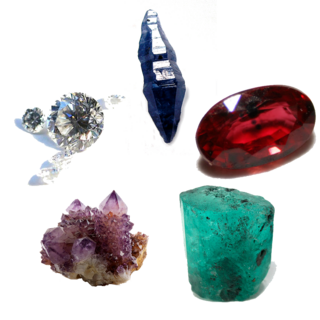

Amethyst is a violet variety of quartz. The name comes from the Koine Greek αμέθυστοςamethystos from α-a-, "not" and μεθύσκωmethysko / μεθώmetho, "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that the stone protected its owner from drunkenness. Ancient Greeks wore amethyst and carved drinking vessels from it in the belief that it would prevent intoxication.

Amblygonite is a fluorophosphate mineral, (Li,Na)AlPO4(F,OH), composed of lithium, sodium, aluminium, phosphate, fluoride and hydroxide. The mineral occurs in pegmatite deposits and is easily mistaken for albite and other feldspars. Its density, cleavage and flame test for lithium are diagnostic. Amblygonite forms a series with montebrasite, the low fluorine endmember. Geologic occurrence is in granite pegmatites, high-temperature tin veins, and greisens. Amblygonite occurs with spodumene, apatite, lepidolite, tourmaline, and other lithium-bearing minerals in pegmatite veins. It contains about 10% lithium, and has been utilized as a source of lithium. The chief commercial sources have historically been the deposits of California and France.

Beryl ( BERR-əl) is a mineral composed of beryllium aluminium silicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2Si6O18. Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring hexagonal crystals of beryl can be up to several meters in size, but terminated crystals are relatively rare. Pure beryl is colorless, but it is frequently tinted by impurities; possible colors are green, blue, yellow, pink, and red (the rarest). It is an ore source of beryllium.

A gemstone is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. Certain rocks and occasionally organic materials that are not minerals may also be used for jewelry and are therefore often considered to be gemstones as well. Most gemstones are hard, but some softer minerals such as brazilianite may be used in jewelry because of their color or luster or other physical properties that have aesthetic value. However, generally speaking, soft minerals are not typically used as gemstones by virtue of their brittleness and lack of durability.

Topaz is a silicate mineral made of aluminum and fluorine with the chemical formula Al2SiO4(F, OH)2. It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can make it pale blue or golden brown to yellow-orange. Topaz is often treated with heat or radiation to make it a deep blue, reddish-orange, pale green, pink, or purple.

Tourmaline is a crystalline silicate mineral group in which boron is compounded with elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. This gemstone comes in a wide variety of colors.

The mineral or gemstone chrysoberyl is an aluminate of beryllium with the formula BeAl2O4. The name chrysoberyl is derived from the Greek words χρυσός chrysos and βήρυλλος beryllos, meaning "a gold-white spar". Despite the similarity of their names, chrysoberyl and beryl are two completely different gemstones, although they both contain beryllium. Chrysoberyl is the third-hardest frequently encountered natural gemstone and lies at 8.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, between corundum (9) and topaz (8).

Rhodochrosite is a manganese carbonate mineral with chemical composition MnCO3. In its pure form (rare), it is typically a rose-red colour, but it can also be shades of pink to pale brown. It streaks white, and its Mohs hardness varies between 3.5 and 4.5. Its specific gravity is between 3.45 and 3.6. The crystal system of rhodochrosite is trigonal, with a structure and cleavage in the carbonate rhombohedral system. The carbonate ions (CO2−

3) are arranged in a triangular planar configuration, and the manganese ions (Mn2+) are surrounded by six oxygen ions in an octahedral arrangement. The MnO6 octahedra and CO3 triangles are linked together to form a three-dimensional structure. Crystal twinning is often present. It can be confused with the manganese silicate rhodonite, but is distinctly softer. Rhodochrosite is formed by the oxidation of manganese ore, and is found in South Africa, China, and the Americas. It is one of the national symbols of Argentina and the state of Colorado.

Azurite or Azure spar is a soft, deep-blue copper mineral produced by weathering of copper ore deposits. During the early 19th century, it was also known as chessylite, after the type locality at Chessy-les-Mines near Lyon, France. The mineral, a basic carbonate with the chemical formula Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2, has been known since ancient times, and was mentioned in Pliny the Elder's Natural History under the Greek name kuanos (κυανός: "deep blue," root of English cyan) and the Latin name caeruleum. Copper (Cu2+) gives it its blue color.

Anglesite is a lead sulfate mineral with the chemical formula PbSO4. It occurs as an oxidation product of primary lead sulfide ore, galena. Anglesite occurs as prismatic orthorhombic crystals and earthy masses, and is isomorphous with barite and celestine. It contains 74% of lead by mass and therefore has a high specific gravity of 6.3. Anglesite's color is white or gray with pale yellow streaks. It may be dark gray if impure.

Dioptase is an intense emerald-green to bluish-green mineral that is cyclosilicate of copper. It is transparent to translucent. Its luster is vitreous to sub-adamantine. Its formula is Cu6Si6O18·6H2O, also reported as CuSiO2(OH)2. It has a Mohs hardness of 5, the same as tooth enamel. Its specific gravity is 3.28–3.35, and it has two perfect and one very good cleavage directions. Additionally, dioptase is very fragile, and specimens must be handled with great care. It is a trigonal mineral, forming six-sided crystals that are terminated by rhombohedra.

Chrysocolla ( KRIS-ə-KOL-ə) is a hydrous copper phyllosilicate mineral and mineraloid with the formula Cu

2 – xAl

x(H

2Si

2O

5)(OH)

4⋅nH

2O (x < 1) or (Cu, Al)

2H

2Si

2O

5(OH)

4⋅nH

2O).

Cordierite (mineralogy) or iolite (gemology) is a magnesium iron aluminium cyclosilicate. Iron is almost always present, and a solid solution exists between Mg-rich cordierite and Fe-rich sekaninaite with a series formula: (Mg,Fe)2Al3(Si5AlO18) to (Fe,Mg)2Al3(Si5AlO18). A high-temperature polymorph exists, indialite, which is isostructural with beryl and has a random distribution of Al in the (Si,Al)6O18 rings. Cordierite is also synthesized and used in high temperature applications such as catalytic converters and pizza stones.

Tsavorite or tsavolite is a variety of the garnet group species grossular, a calcium-aluminium garnet with the formula Ca3Al2Si3O12. Trace amounts of vanadium or chromium provide the green color.

Demantoid is the green gemstone variety of the mineral andradite, a member of the garnet group of minerals. Andradite is a calcium- and iron-rich garnet. The chemical formula is Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 with chromium substitution as the cause of the demantoid green color. Ferric iron is the cause of the yellow in the stone.

Tenorite, sometimes also called Black Copper, is a copper oxide mineral with the chemical formula CuO. The chemical name is Copper(II) oxide or cupric oxide.

Jeremejevite is an aluminium borate mineral with variable fluoride and hydroxide ions. Its chemical formula is Al6B5O15(F,OH)3. It is considered as one of the rarest, thus one of the most expensive stones. For nearly a century, it was considered as one of the rarest gemstones in the world.

Pseudomalachite is a phosphate of copper with hydroxyl, named from the Greek for "false" and "malachite", because of its similarity in appearance to the carbonate mineral malachite, Cu2(CO3)(OH)2. Both are green coloured secondary minerals found in oxidised zones of copper deposits, often associated with each other. Pseudomalachite is polymorphous with reichenbachite and ludjibaite. It was discovered in 1813. Prior to 1950 it was thought that dihydrite, lunnite, ehlite, tagilite and prasin were separate mineral species, but Berry analysed specimens labelled with these names from several museums, and found that they were in fact pseudomalachite. The old names are no longer recognised by the IMA.

Paramelaconite is a rare, black-colored copper(I,II) oxide mineral with formula CuI

2CuII

2O3 (or Cu4O3). It was discovered in the Copper Queen Mine in Bisbee, Arizona, about 1890. It was described in 1892 and more fully in 1941. Its name is derived from the Greek word for "near" and the similar mineral melaconite, now known as tenorite.

Aquamarine is a pale-blue to light-green variety of the beryl family, with its name relating to water and sea. The color of aquamarine can be changed by heat, with a goal to enhance its physical appearance. It is the birth stone of March.