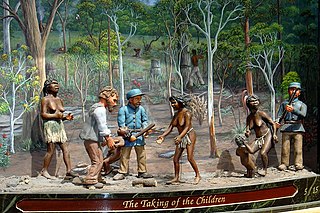

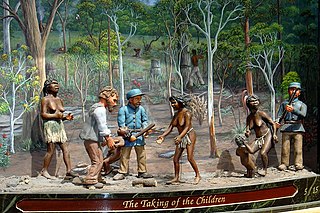

The Stolen Generations were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as "half-caste" children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905 and 1967, although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s.

Native title is the designation given to the common law doctrine of Aboriginal title in Australia, which is the recognition by Australian law that Indigenous Australians have rights and interests to their land that derive from their traditional laws and customs. The concept recognises that in certain cases there was and is a continued beneficial legal interest in land held by Indigenous peoples which survived the acquisition of radical title to the land by the Crown at the time of sovereignty. Native title can co-exist with non-Aboriginal proprietary rights and in some cases different Aboriginal groups can exercise their native title over the same land.

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) (1987–1991), also known as the Muirhead Commission, was a Royal Commission appointed by the Australian Government in October 1987 to study and report upon the underlying social, cultural and legal issues behind the deaths in custody of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, in the light of the high level of such deaths in the 1980s.

Reconciliation Australia is a non-government, not-for-profit foundation established in January 2001 to promote a continuing national focus for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. It was established by the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (CAR) and subsequently superseded that body in 2001. It organises National Reconciliation Week each year.

Aboriginal deaths in custody is a political and social issue in Australia. It rose in prominence in the early 1980s, with Aboriginal activists campaigning following the death of 16-year-old John Peter Pat in 1983. Subsequent deaths in custody, considered suspicious by families of the deceased, culminated in the 1987 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC).

The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897, long name A Bill to make Provision for the better Protection and Care of the Aboriginal and Half-caste Inhabitants of the Colony, and to make more effectual Provision for Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Opium, was an Act of the Parliament of Queensland. It was the first instrument of separate legal control over Aboriginal peoples, and was more restrictive than any contemporary legislation operating in other states. It also implemented the creation of Aboriginal reserves to control the dwelling places and movement of the people.

Indigenous Australian self-determination, also known as Aboriginal Australian self-determination, is the power relating to self-governance by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. It is the right of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to determine their own political status and pursue their own economic, social and cultural interests. Self-determination asserts that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should direct and implement Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy formulation and provision of services. Self-determination encompasses both Aboriginal land rights and self-governance, and may also be supported by a treaty between a government and an Indigenous group in Australia.

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage to groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They include the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. The term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or the person's specific cultural group, is often preferred, though the terms First Nations of Australia, First Peoples of Australia and First Australians are also increasingly common.

An Australian Aboriginal sacred site is a place deemed significant and meaningful by Aboriginal Australians based on their beliefs. It may include any feature in the landscape, and in coastal areas, these may lie underwater. The site's status is derived from an association with some aspect of social and cultural tradition, which is related to ancestral beings, collectively known as Dreamtime, who created both physical and social aspects of the world. The site may have its access restricted based on gender, clan or other Aboriginal grouping, or other factors.

A community legal centre (CLC) is the Australian term for an independent not-for-profit organisation providing legal aid services, that is, provision of assistance to people who are unable to afford legal representation and access to the court system. They provide legal advice and traditional casework for free, primarily funded by federal, state and local government. Working with clients who are mostly the most disadvantaged and vulnerable people in Australian society, they also work with other agencies to address related problems, including financial, social and health issues. Their functions may include campaigning for law reform and developing community education programs.

Indigenous Australians are both convicted of crimes and imprisoned at a disproportionately high rate in Australia, as well as being over-represented as victims of crime. The issue is a complex one, to which federal and state governments, as well as Indigenous groups, have responded with various analyses and numerous programs and measures. As of September 2019, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners represented 28% of the total adult prisoner population, while accounting for 3.3% of the general population.

Punishment in Australia arises when an individual has been convicted of breaking the law through the Australian criminal justice system. Australia uses prisons, as well as community corrections. The death penalty has been abolished, and corporal punishment is no longer used. Prison labour occurs in Australia, prisoners are involved in many types of work with some paid as little as $0.82 per hour. Before the colonisation of Australia by Europeans, Indigenous Australians had their own traditional punishments, some of which are still practised. The most severe punishment by law which can be imposed in Australia is life imprisonment. In the most extreme cases of murder, courts in the states and territories can impose life imprisonment without parole, thus ordering the convicted person to spend the rest of their lives in prison.

Indigenous land rights in Australia, also known as Aboriginal land rights in Australia, relate to the rights and interests in land of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, and the term may also include the struggle for those rights. Connection to the land and waters is vital in Australian Aboriginal culture and to that of Torres Strait Islander people, and there has been a long battle to gain legal and moral recognition of ownership of the lands and waters occupied by the many peoples prior to colonisation of Australia starting in 1788, and the annexation of the Torres Strait Islands by the colony of Queensland in the 1870s.

The Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia (ALSWA) is an organisation in Western Australia, founded in the early 1970s, that provides legal services to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. It receives financial grants from the Commonwealth Department of the Australian Attorney General and follows conditions required by that Department. It commenced its Custody Notification Service on 2 October 2019.

The Aboriginal Legal Service (NSW/ACT) (ALS), known also as Aboriginal Legal Service, is a community-run organisation in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, founded in 1970 to provide legal services to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders and based in the inner-Sydney suburb of Redfern. It now has branches across NSW and ACT, with its head office in Castlereagh Street, Sydney and a branch office in Regent Street, Redfern.

Gerry Georgatos, born in 1962, is a university researcher and academic and a social justice and human rights campaigner, who has campaigned for prison reform, as well as championing the rights of the impoverished and marginalised and the homeless.

The Closing the Gap framework is an Australian government strategy that aims to reduce disadvantage among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, based on seven targets. From adoption in 2008, after meetings with the Close the Gap social justice campaign, until 2018, the federal and state and territory governments worked together via the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) on the framework, with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet producing a report at the end of each year analysing progress on each of its seven targets.

Julieka Ivanna Dhu was a 22-year-old Australian Aboriginal woman who died in police custody in South Hedland, Western Australia, in 2014. On 2 August that year, police responded to a report that Dhu's partner had violated an apprehended violence order. Upon arriving at their address, the officers arrested both Dhu and her partner after realising there was also an outstanding arrest warrant for unpaid fines against Dhu. She was detained in police custody in South Hedland and was ordered to serve four days in custody in default of her debt.

The First Nations Deaths In Custody Watch Committee was first registered on 7 January 2015, but its first annual report under that name was for 2017. It is the successor to the Deaths In Custody Watch Committee (WA), which was a social justice organisation operating from Perth, Western Australia from 1996 until it underwent a constitutional change early 2017. It is a Public Benevolent Institution whose main concern is Aboriginal Australian deaths in custody.

The Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement (ALRM) is an ATSILS in South Australia, providing pro bono legal services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the state. Its headquarters are in Adelaide, with branch offices in Ceduna, Port Augusta and Port Lincoln. It an independent organisation governed by a board of all Aboriginal Australians, which also acts as a lobby group to advocate for justice for Aboriginal people as well as providing programs which aim to address issues which raise the likelihood of Aboriginal people encountering the criminal justice system.