Computer art is art in which computers play a role in the production or display of the artwork. Such art can be an image, sound, animation, video, CD-ROM, DVD-ROM, video game, website, algorithm, performance or gallery installation. Many traditional disciplines are now integrating digital technologies and, as a result, the lines between traditional works of art and new media works created using computers has been blurred. For instance, an artist may combine traditional painting with algorithm art and other digital techniques. As a result, defining computer art by its end product can thus be difficult. Computer art is bound to change over time since changes in technology and software directly affect what is possible.

The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) is an artistic and cultural centre on The Mall in London, just off Trafalgar Square. Located within Nash House, part of Carlton House Terrace, near the Duke of York Steps and Admiralty Arch, the ICA contains galleries, a theatre, two cinemas, a bookshop and a bar.

Frederick Rowland Emett OBE, known as Rowland Emett, was an English cartoonist and constructor of whimsical kinetic sculpture.

Bruce Lacey was a British artist, performer and eccentric. After completing his national service in the Navy he became established on the avant garde scene with his performance art and mechanical constructs. He has been closely associated with The Alberts performance group and The Goon Show. He made the props and had an acting part in Richard Lester's The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film.

Andrew Gordon Speedie Pask was a British cybernetician, inventor and polymath who made multiple contributions to cybernetics, educational psychology, educational technology, applied episteomology, chemical computing, architecture, and systems art. During his life, he gained three doctorate degrees. He was an avid writer, with more than two hundred and fifty publications which included a variety of journal articles, books, periodicals, patents, and technical reports. He worked as an academic and researcher for a variety of educational settings, research institutes, and private stakeholders including but not limited to the University of Illinois, Concordia University, the Open University, Brunel University and the Architectural Association School of Architecture. He is known for the development of conversation theory.

Kenneth Charles Knowlton was an American computer graphics pioneer, artist, mosaicist and portraitist. In 1963, while working at Bell Labs, he developed the BEFLIX programming language for creating bitmap computer-produced movies. In 1966, also at Bell Labs, he and Leon Harmon created the computer artwork Computer Nude .

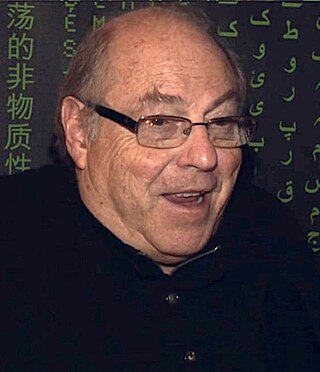

Roy Ascott FRSA is a British artist, who works with cybernetics and telematics on an art he calls technoetics by focusing on the impact of digital and telecommunications networks on consciousness. Since the 1960s, Ascott has been a practitioner of interactive computer art, electronic art, cybernetic art and telematic art.

Peter Zinovieff was a British composer, musician and inventor. In the late 1960s, his company, Electronic Music Studios (EMS), made the VCS3, a synthesizer used by many early progressive rock bands such as Pink Floyd and White Noise, and Krautrock groups as well as more pop-orientated artists, including Todd Rundgren and David Bowie. In later life, he worked primarily as a composer of electronic music.

The Computer Arts Society (CAS) was founded in 1968, in order to encourage the creative use of computers in the arts.

Edward Ihnatowicz was a Polish cybernetic art sculptor active in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His sculptures explored the interaction between his robotic works and the audience.

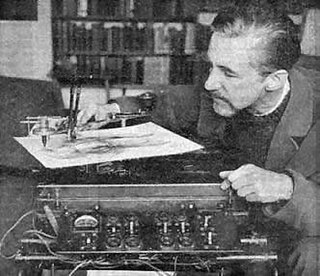

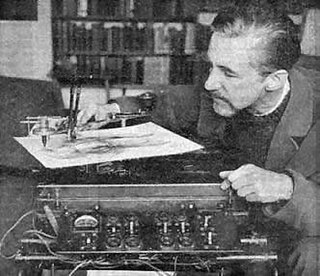

Desmond Paul Henry (1921–2004) was a Manchester University Lecturer and Reader in Philosophy (1949–82). He was one of the first British artists to experiment with machine-generated visual effects at the time of the emerging global computer art movement of the 1960s. During this period, Henry constructed a succession of three electro-mechanical drawing machines from modified bombsight analogue computers which were employed in World War II bombers to calculate the accurate release of bombs onto their targets. Henry's machine-generated effects resemble complex versions of the abstract, curvilinear graphics which accompany Microsoft's Windows Media Player. Henry's machine-generated effects may therefore also be said to represent early examples of computer graphics: "the making of line drawings with the aid of computers and drawing machines".

Systems art is art influenced by cybernetics and systems theory, reflecting on natural systems, social systems, and the social signs of the art world itself.

Jasia Reichardt is a British art critic, curator, art gallery director, teacher and prolific writer, specialist in the emergence of computer art. In 1968 she was curator of the landmark Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts. She is generally known for her work on experimental art. After the deaths of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson she catalogued their archive and looks after their legacy.

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular processes such as feedback systems where outputs are also inputs. It is concerned with general principles that are relevant across multiple contexts, including in ecological, technological, biological, cognitive and social systems and also in practical activities such as designing, learning, and managing.

Keith Albarn was an English artist. He was the father of musician Damon Albarn and artist Jessica Albarn.

Cybernetic art is contemporary art that builds upon the legacy of cybernetics, where feedback involved in the work takes precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. The relationship between cybernetics and art can be summarised in three ways: cybernetics can be used to study art, to create works of art or may itself be regarded as an art form in its own right.

William Fetter, also known as William Alan Fetter or Bill Fetter, was an American graphic designer and pioneer in the field of computer graphics. He explored the perspective fundamentals of computer animation of a human figure from 1960 on and was the first to create a human figure as a 3D model. The First Man was a pilot in a short 1964 computer animation, also known as Boeing Man and now as Boeman by the Boeing company. Fetter preferred the term "Human Figure" for the pilot. In 1960, working in a team supervised by Verne Hudson, he helped coin the term Computer graphics. He was art director at the Boeing Company in Wichita.

The Doors Are Open is a 1968 black-and-white documentary about the American rock group the Doors. It was produced by Jo Durden-Smith for Granada TV and directed by John Sheppard and first aired in the United Kingdom on 4 October 1968. The programme combines footage of the Doors playing live at London's Roundhouse venue, interviews with the band members and contemporary news snippets of world current affairs - protests at the 1968 Democratic Convention, French riots, statements from politicians and footage of the Vietnam War etc.

Catherine Mason is an art historian and author who specialises in digital art, especially computer art.

George L. Mallen FBCS FRSA is a British businessman who has been a pioneer of creative computer systems since 1962. He co-founded the Computer Arts Society (CAS) with Alan Sutcliffe and John Lansdown in 1968. In 1970, he led CAS members in creating Ecogame, the "first digitally driven, multi-player, interactive gaming system in the UK". Also in 1970, he founded the company System Simulation Ltd, one of the longest established software companies in the United Kingdom.