Related Research Articles

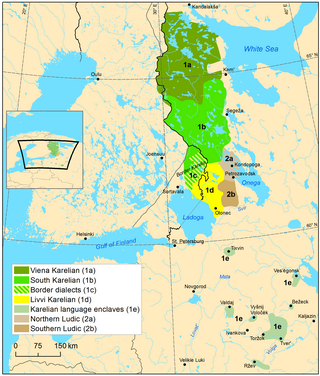

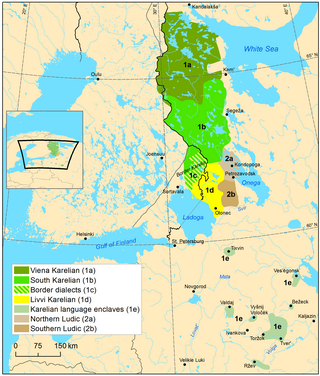

Karelian is a Finnic language spoken mainly in the Russian Republic of Karelia. Linguistically, Karelian is closely related to the Finnish dialects spoken in eastern Finland, and some Finnish linguists have even classified Karelian as a dialect of Finnish, though in the modern day it is widely considered a separate language. Karelian is not to be confused with the Southeastern dialects of Finnish, sometimes referred to as karjalaismurteet in Finland. In the Russian 2020–2021 census, around 9,000 people spoke Karelian natively, but around 14,000 said to be able to speak the language. There are around 11,000 speakers of Karelian in Finland. And around 30,000 have at least some knowledge of Karelian in Finland.

Saimaa is a lake located in the Finnish Lakeland area in southeastern Finland. With a surface area of approximately 4,279 square kilometres (1,652 sq mi), it is the largest lake in Finland, and the fourth-largest natural freshwater lake in Europe.

Inari Sámi is a Sámi language spoken by the Inari Sámi of Finland. It has approximately 400 speakers, the majority of whom are middle-aged or older and live in the municipality of Inari. According to the Sámi Parliament of Finland, 269 persons used Inari Sámi as their first language. It is the only Sámi language that is spoken exclusively in Finland. The language is classified as being seriously endangered, as few children learn it; however, more and more children are learning it in language nests. In 2018, Inari Sámi had about 400 speakers; due to revival efforts, the number had increased.

Lake Inari is the largest lake in Sápmi and the third-largest lake in Finland. It is located in the northern part of Lapland, north of the Arctic Circle. The lake is 117–119 metres (384–390 ft) above sea level, and is regulated at the Kaitakoski power plant in Russia. The freezing period normally extends from November to early June.

Gákti is the Northern Sámi word used by non-Sámi speakers to refer to many different types of traditional clothing worn by the Sámi in northern areas of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The gákti is worn both in ceremonial contexts and while working, particularly when herding reindeer. The traditional Sami outfit is characterized by a dominant color adorned with bands of contrasting colours, plaits, pewter embroidery, tin art, and often a high collar. In the Norwegian language the garment is called a 'kofte', and in Swedish it is called 'kolt'.

The exessive case is a grammatical case that denotes a transition away from a state. It is a rare case found in certain dialects of Baltic-Finnic languages. It completes the series of "to/in/from a state" series consisting of the translative case, the essive case and the exessive case.

The Institute for the Languages of Finland, better known as Kotus, is a governmental linguistic research institute of Finland geared to studies of Finnish, Swedish, the Sami languages, Romani language, as well as Finnish Sign Language and Finland-Swedish Sign Language.

Rauma dialect is a Southwestern dialect of Finnish spoken in the town of Rauma, Finland.

The two main official languages of Finland are Finnish and Swedish. There are also several official minority languages: three variants of Sami, as well as Romani, Finnish Sign Language, Finland-Swedish Sign Language and Karelian.

Different conventions exist around the world for date and time representation, both written and spoken.

Finnish Kalo is a language of the Romani language family spoken by Finnish Kale. The language is related to but not mutually intelligible with Scandoromani or Angloromani.

Finnish is a Finnic language of the Uralic language family, spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside of Finland. Finnish is one of the two official languages of Finland, alongside Swedish. In Sweden, both Finnish and Meänkieli are official minority languages. Kven, which like Meänkieli is mutually intelligible with Finnish, is spoken in the Norwegian counties of Troms and Finnmark by a minority of Finnish descent.

Date and time notation in Sweden mostly follows the ISO 8601 standard: dates are generally written in the form YYYY-MM-DD. Although this format may be abbreviated in a number of ways, almost all Swedish date notations state the month between the year and the day. Months are not capitalised when written. The week number may also be used in writing and in speech. Times are generally written using 24-hour clock notation, with full stops as separators, although 12-hour clock notation is more frequently used in speech.

Finland-Swedish Sign Language is a moribund sign language in Finland. It is now used mainly in private settings by older adults who attended the only Swedish school for the deaf in Finland, which was established in the mid-19th century by Carl Oscar Malm but closed in 1993. However, it has recently been taught to some younger individuals. Some 90 persons had it as their native language within Finland in 2014 and it is spoken by around 300 people in total.

New Finns are those people in Finland’s population who have a non-ethnic Finnish background and who reside permanently in the country. A new Finn may have various backgrounds; including immigrant, immigrant-origin, refugee and/or having come to Finland for family reasons. The term is especially used to emphasize those that have a Finnish citizenship and carry Finnish passports, to those foreigners who live permanently in Finland and intend to be naturalized in Finland at some point in the future. Finland has experienced large-scale, continuous non-European immigration only within the past couple of decades. The term uussuomalainen is beginning to come into usage to commonly refer to these new, naturalized Finns, who are beginning to change and affect the national landscape of the country.

In Russia, dates are usually written in "day month year" (DMY) order. The 12-hour notation is often used in the spoken language, and the 24-hour notation is used in writing.

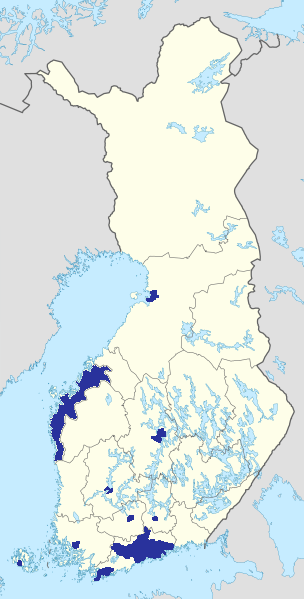

Southwest Finnish dialects are Western Finnish dialects spoken in Southwest Finland and Satakunta.

South Ostrobothnian dialect is a Western Finnish dialect. It is traditionally spoken in the region of South Ostrobothnia and parts of Coastal Ostrobothnia. The South Ostrobothnian dialect has many features that are unique to the region of South Ostrobothnia.

Tavastian dialects are Western Finnish dialects spoken in Pirkanmaa, Päijät-Häme, Kanta-Häme, and in parts of Satakunta, Uusimaa and Kymenlaakso. The dialect spoken in the city of Tampere is part of the Tavastian dialects. The Tavastian dialects have influenced other Finnish dialects.

The Tver Karelian dialect is a dialect of the Karelian language spoken in the Tver Oblast. It is descended from 17th century South Karelian speakers who migrated to the Tver region.

References

- ↑ "Miten päiväys merkitään?". Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ↑ "Räkneord och datum - Institutet för de inhemska språken". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Swedish). Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ "Ajanilmaukset: lyhenteet (ajan yksiköt ja viikonpäivät)". Kielitoimiston ohjepankki (in Finnish). Kotimaisten kielten keskus – Institute for the Languages of Finland. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ↑ "Fråga: Hur skriver man vecka 5 om man inte vill skriva ut vecka?". Frågelådan i svenska (in Swedish). Institutet för språk och folkminnen – Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore. Retrieved 14 October 2023.