Balaam, son of Beor, was a biblical character, a non-Israelite prophet and diviner who lived in Pethor, a region or settlement which has never been located, but is thought to have been between the region of Iraq and northern Syria in what is now southeastern Turkey. According to chapters Numbers 22–24 of the Book of Numbers, he was hired by King Balak of Moab to curse Israel, but instead he blessed the Israelites, as dictated by God. Subsequently, the plan to entice the Israelites into idol worship and sexual immorality is attributed to him . Balaam is also mentioned in the Book of Micah.

Baal, or Baʻal, was a title and honorific meaning 'owner' or 'lord' in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to gods. Scholars previously associated the theonym with solar cults and with a variety of unrelated patron deities, but inscriptions have shown that the name Ba'al was particularly associated with the storm and fertility god Hadad and his local manifestations.

Asherah was a goddess in ancient Semitic religions. She also appears in Hittite writings as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s), and as Athirat in Ugarit. Some scholars hold that Yahweh and Asherah were a consort pair in ancient Israel and Judah, while others disagree.

The Moabite language, also known as the Moabite dialect, is an extinct sub-language or dialect of the Canaanite languages, themselves a branch of Northwest Semitic languages, formerly spoken in the region described in the Bible as Moab in the early 1st millennium BC.

The Canaanite languages, sometimes referred to as Canaanite dialects, are one of three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Amorite. These closely related languages originate in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and were spoken by the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of an area encompassing what is today, Israel, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, Lebanon, Syria, as well as some areas of southwestern Turkey (Anatolia), western and southern Iraq (Mesopotamia) and the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia.

Mot was the Canaanite god of death and the Underworld. He was also known to the people of Ugarit and in Phoenicia, where Canaanite religion was widespread. The main source of information about Mot in Canaanite mythology comes from the texts discovered at Ugarit, but he is also mentioned in the surviving fragments of Philo of Byblos's Greek translation of the writings of the Phoenician Sanchuniathon.

Dushara, also transliterated as Dusares, is a pre-Islamic Arabian god worshipped by the Nabataeans at Petra and Madain Saleh. Safaitic inscriptions imply he was the son of Al-Lat, and that he assembled in the heavens with other gods. He is called "Dushara from Petra" in one inscription. Dushara was expected to bring justice if called by the correct ritual.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic itself represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate, but exclude the religions of "non-Semitic" speakers of the region such as Egyptians, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Urartians, Luwians, Minoans, Greeks, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Philistines and Parthians.

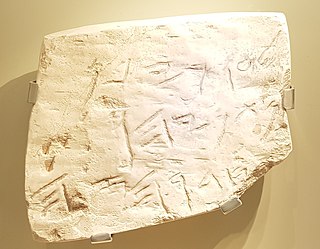

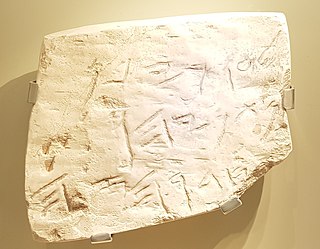

Deir Alla is the site of an ancient Near Eastern town in Balqa Governorate, Jordan. The Deir Alla Inscription, datable to ca. 840–760 BCE, was found here.

Red letter edition bibles are those in which the words considered as being spoken by Jesus Christ are printed in red ink.

The West Semitic languages are a proposed major sub-grouping of ancient Semitic languages. The term was first coined in 1883 by Fritz Hommel.

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze Age. The oldest coherent texts are in Ugaritic, dating to the Late Bronze Age, which by the time of the Bronze Age collapse are joined by Old Aramaic, and by the Iron Age by Sutean and the Canaanite languages.

El Shaddai or just Shaddai is one of the names of God in Judaism. El Shaddai is conventionally translated into English as God Almighty.

Pethor or Petor (פְּתוֹר) in the Hebrew Bible is the home of the prophet Balaam. In the Book of Numbers, Pethor is described as being located "by the river of the land of the children of his people". The River usually refers in the Bible to the Euphrates River, the rest of the description is somewhat vague and perhaps corrupted. In Deuteronomy, Balaam is from "Pethor of Mesopotamia". It is widely accepted that Pethor is the town Pitru, which is mentioned in ancient Assyrian records.

Khirbet el-Qom is an archaeological site in the village of al-Kum, West Bank, in the territory of the biblical Kingdom of Judah, between Lachish and Hebron, 14 km (8.7 mi) to the west of the latter.

Samalian was a Semitic language spoken and first attested in Samʼal.

Jo Ann Hackett is an American scholar of the Hebrew Bible and of Biblical Hebrew and other ancient Northwest Semitic languages such as Phoenician, Punic, and Aramaic.

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.

The Revadim Asherah is an artifact from Revadim representing a genre of Asherah figurines. Like the inscriptions found at Khirbet el-Qom and Kuntillet Ajrud, these findings revealed Asherah's prominence in Canaanite and Hebrew religion.