Related Research Articles

Hatshepsut was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, after Sobekneferu.

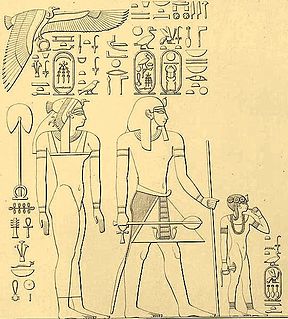

Ahmose was an Ancient Egyptian queen in the Eighteenth Dynasty. She was the Great Royal Wife of the dynasty's third pharaoh, Thutmose I, and the mother of the queen and pharaoh Hatshepsut. Her name means "Born of the Moon".

Thutmose I was the third pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He received the throne after the death of the previous king, Amenhotep I. During his reign, he campaigned deep into the Levant and Nubia, pushing the borders of Egypt farther than ever before in each region. He also built many temples in Egypt, and a tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings; he is the first king confirmed to have done this.

Thutmose II was the fourth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. His reign is generally dated from 1493 to 1479 BC. His body was found in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut and can be viewed today in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Cairo.

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth century BC and the eleventh century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties of Egypt. Radiocarbon dating places the exact beginning of the New Kingdom between 1570 BC and 1544 BC. The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt's most prosperous time and marked the peak of its power.

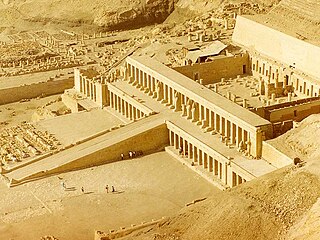

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of the Theban Necropolis.

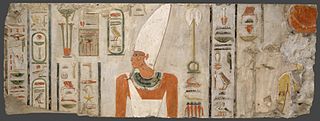

Mentuhotep II, also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty. He is credited with reuniting Egypt, thus ending the turbulent First Intermediate Period and becoming the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom. He reigned for 51 years, according to the Turin King List. Mentuhotep II succeeded his father Intef III on the throne and was in turn succeeded by his son Mentuhotep III.

God's Wife of Amun was the highest-ranking priestess of the Amun cult, an important religious institution in ancient Egypt. The cult was centered in Thebes in Upper Egypt during the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth dynasties. The office had political importance as well as religious, since the two were closely related in ancient Egypt.

The Red Chapel of Hatshepsut or the Chapelle rouge was a religious shrine in Ancient Egypt.

Great Royal Wife, or alternatively, Chief King's Wife, is the title that was used to refer to the principal wife of the pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, who served many official functions.

Neferure was an Egyptian princess of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the daughter of two pharaohs, Hatshepsut and Thutmose II. She served in high offices in the government and the religious administration of Ancient Egypt.

Mutemwiya was a minor wife of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Thutmose IV, and the mother of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. Mutemwiya's name means "Mut in the divine barque". While unconfirmed, it has been suggested that she acted as regent during the minority of her son Amenhotep III.

Ahhotep I was an ancient Egyptian queen who lived circa 1560–1530 BC, during the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the daughter of Queen Tetisheri and Senakhtenre Ahmose, and was probably the sister, as well as the queen consort, of Pharaoh Seqenenre Tao ll. Ahhotep I had a long and influential life. She ruled as regent for her son Ahmose I for a time.

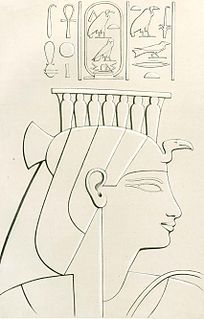

Senseneb was the mother of Pharaoh Thutmose I of the early New Kingdom. She only bore the title of King's mother (Mw.t-nswt) and is therefore thought to have been a commoner. Senseneb is known thanks to stele Cairo CG 34006, from Wadi Halfa, where she is shown swearing an oath of allegiance as the king's mother on the coronation of her son Thutmose I. Senseneb is also depicted on painted reliefs from the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri.

Hapuseneb was the High Priest of Amun during the reign of Hatshepsut.

The Temple of Hatshepsut is a mortuary temple built during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Located opposite the city of Luxor, it is considered to be a masterpiece of ancient architecture. Its three massive terraces rise above the desert floor and into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. Her tomb, KV20, lies inside the same massif capped by El Qurn, a pyramid for her mortuary complex. At the edge of the desert, 1 km (0.62 mi) east, connected to the complex by a causeway lies the accompanying valley temple. Across the river Nile, the whole structure points towards the monumental Eighth Pylon, Hatshepsut's most recognizable addition to the Temple of Karnak and the site from which the procession of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley departed. The temple's twin functions are identified by its axes: its main east-west axis served to receive the barque of Amun-Re at the climax of the festival, while its north-south axis represented the life cycle of the pharaoh from coronation to rebirth.

Nefrubity was an ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th Dynasty. She was the daughter of Pharaoh Thutmose I and Ahmose, the sister of Hatshepsut and the half-sister of Thutmose II, Wadjmose and Amenmose.

Ahmose called Turo was Viceroy of Kush under Amenhotep I and Thutmose I.

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This dynasty is also known as the Thutmosid Dynasty for the four pharaohs named Thutmose.

Women in ancient Egypt had some special rights other women did not have in other comparable societies. They could own property and were, at court, legally equal to men. However, Ancient Egypt was a society dominated by men and was patriarchal in nature. Women could not have important positions in administration, though there were female rulers and even female pharaohs. Women at the royal court gained their positions by relationship to male kings.

References

- ↑ Roehrig, p. 87.

- ↑ Roehrig, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Naville, Edouard (1897). The Temple of Deir El Bahari: Part II. London: Fellow of King's College. p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Naville, Edouard (1898). The Temple of Deir El Bahari: Part III. London: Fellow of King's College. p. 6.

- 1 2 Galán, José M. (2014). Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 33.

- Cooney, Kara. The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. New York: Broadway Books, 2014.

- Roehrig, Catharine H., Dreyfus, Renée, Keller, Cathleen A. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-173-5.