Related Research Articles

Dangerous Liaisons is a 1988 American period romantic drama film directed by Stephen Frears from a screenplay by Christopher Hampton, based on his 1985 play Les liaisons dangereuses, itself adapted from the 1782 French novel of the same name by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. It stars Glenn Close, John Malkovich, Michelle Pfeiffer, Uma Thurman, Swoosie Kurtz, Mildred Natwick, Peter Capaldi and Keanu Reeves.

Madame Bovary, originally published as Madame Bovary: Provincial Manners, is a novel by French writer Gustave Flaubert, published in 1857. The eponymous character lives beyond her means in order to escape the banalities and emptiness of provincial life.

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein, commonly known as Madame de Staël, was a prominent philosopher, woman of letters, and political theorist in both Parisian and Genevan intellectual circles. She was the daughter of banker and French finance minister Jacques Necker and Suzanne Curchod, a respected salonhostess. Throughout her life, she held a moderate stance during the tumultuous periods of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, persisting until the time of the French Restoration.

The Dionne quintuplets are the first quintuplets known to have survived their infancy. The identical girls were born just outside Callander, Ontario, near the village of Corbeil. All five survived to adulthood.

Les Liaisons dangereuses is a French epistolary novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, first published in four volumes by Durand Neveu from March 23, 1782.

Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue is a 1791 novel by Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, better known as the Marquis de Sade. Justine is set just before the French Revolution in France and tells the story of a young girl who goes under the name of Thérèse. Her story is recounted to Madame de Lorsagne while defending herself for her crimes, en route to punishment and death. She explains the series of misfortunes that led to her present situation.

Yolande Martine Gabrielle de Polastron, Duchess of Polignac was the favourite of Marie Antoinette, whom she first met when she was presented at the Palace of Versailles in 1775, the year after Marie Antoinette became the Queen of France. She was considered one of the great beauties of pre-Revolutionary society, but her extravagance and exclusivity earned her many enemies.

Frank Laurence Lucas was an English classical scholar, literary critic, poet, novelist, playwright, political polemicist, Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and intelligence officer at Bletchley Park during World War II.

Marie-Thérèse Charlotte was the eldest child of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette of France, and their only child to reach adulthood. In 1799 she married her cousin Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême, the eldest son of Charles, Count of Artois, henceforth becoming the Duchess of Angoulême. She was briefly Queen of France in 1830.

Elisabeth Françoise Sophie Lalive de Bellegarde, Comtesse d'Houdetot was a French noblewoman. She is remembered primarily for the brief but intense love she inspired in Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1757, but she was also for fifty years in a relationship with the poet and academician Jean François de Saint-Lambert.

Valmont is a 1989 romantic drama film directed by Miloš Forman and starring Colin Firth, Annette Bening, and Meg Tilly. Based on the 1782 French novel Les Liaisons dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos, and adapted for the screen by Jean-Claude Carrière, the film is about a scheming widow (Merteuil) who bets her ex-lover (Valmont) that he cannot corrupt a recently married honorable woman (Tourvel). During the process of seducing the married woman, Valmont ends up falling in love with her. Earlier, Merteuil learns her secret lover (Gercourt) has discarded her and is about to marry her cousin's daughter- the virginal 15 year old Cécile. As revenge, the jilted Merteuil employs Valmont to seduce Cécile before her marriage to Gercourt.

Journey to the End of the Night is the first novel by Louis-Ferdinand Céline. This semi-autobiographical work follows the adventures of Ferdinand Bardamu in World War I, colonial Africa, the United States and the poor suburbs of Paris where he works as a doctor.

Babraham is a village and civil parish in the South Cambridgeshire district of Cambridgeshire, England, about 6 miles (9.7 km) south-east of Cambridge on the A1307 road.

Sophie Philippine Élisabeth Justine of France was a French princess, a fille de France. She was the sixth daughter and eighth child of King Louis XV and his queen consort, Marie Leszczyńska. First known as Madame Cinquième, she later became Madame Sophie. She and her sisters were collectively known as Mesdames. In 1777, Sophie and her elder sister Adélaïde were both given the title Duchess of Louvois.

Desmond is an epistolary novel by Charlotte Smith, first published in 1792. The novel focuses on politics during the French Revolution.

Les Fugitifs is a French 1986 action comedy film, directed by Francis Veber. It was remade in 1989 as Three Fugitives, also directed by Veber.

Madame Bovary is a 2014 historical romantic drama film directed by Sophie Barthes, based on the 1856 novel of the same name by French author Gustave Flaubert. The film stars Mia Wasikowska, Rhys Ifans, Ezra Miller, Logan Marshall-Green, Henry Lloyd-Hughes, Laura Carmichael, Olivier Gourmet, and Paul Giamatti.

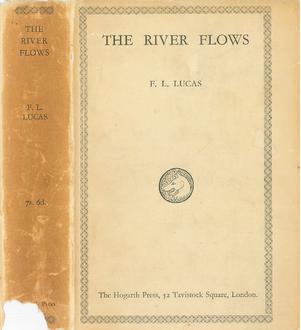

The River Flows is a semi-autobiographical first novel, published in 1926, by the British writer F. L. Lucas. The title is taken from a poem by T'ao Ch'ien, translated by Arthur Waley, three lines from which form the novel's epigraph.

Cécile is an historical novel by the British writer F. L. Lucas. His second novel, first published in 1930, it is a story of love, society and politics in the France of 1775–1776, set largely in Picardy and Paris, which locations form its two parts.

The Woman Clothed with the Sun; being The Confession of John McHaffie concerning his sojourn in the Wilderness among the folk called the Buchanites, is a historical novella by the British writer F. L. Lucas. It purports to be an account, written in 1814 by a Scottish minister of the Kirk in middle age and published posthumously, of his youthful bewitchment by Elspeth Buchan and of the time he spent in the 1780s among the Buchanites. First published in 1937, it was Lucas's second historical novella, the first being The Wild Tulip (1932); he had also published a prize-winning historical novel, Cécile (1930).

References

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.36

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.36

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.61

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.91

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.119

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.240

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.313

- ↑ Proverbs, 5:3-4

- ↑ Lucas, F. L., Journal Under the Terror, 1938 (London 1939), p.113

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.302

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.82

- ↑ Lucas, F. L., Journal Under the Terror, 1938 (London 1939), p.114, p.242

- ↑ The Cambridge Review, 3 March 1939

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.240

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.291

- ↑ Lucas, Doctor Dido, p.135

- ↑ The Times Literary Supplement , 10 Sept. 1938, p.581

- ↑ Tullis Clare in Time and Tide, 24 Sept. 1938, p.1324

- ↑ Forrest Reid in The Spectator, 17 May 1930

- ↑ Desmond Shawe-Taylor in the New Statesman, 24 Sept. 1938, p.460

- ↑ The Cornhill Magazine, vol.158, July-December 1938, p.719

- ↑ D. A. Winstanley in The Cambridge Review, 3 March 1939

- ↑ Flower, Desmond, Fellows in Foolscap – Memoirs of a Publisher (London 1991)

- ↑ Publisher's blurb on dust-wrapper of Lucas's The English Agent, Cassell & Co., 1969

- ↑ The Daily Telegraph obituary, 2 June 1967