Related Research Articles

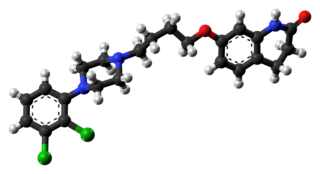

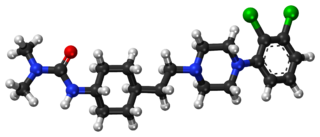

Haloperidol, sold under the brand name Haldol among others, is a typical antipsychotic medication. Haloperidol is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, tics in Tourette syndrome, mania in bipolar disorder, delirium, agitation, acute psychosis, and hallucinations from alcohol withdrawal. It may be used by mouth or injection into a muscle or a vein. Haloperidol typically works within 30 to 60 minutes. A long-acting formulation may be used as an injection every four weeks by people with schizophrenia or related illnesses, who either forget or refuse to take the medication by mouth.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

Aripiprazole, sold under the brand names Abilify and Aristada among others, is an atypical antipsychotic. It is primarily used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Other uses include as an add-on treatment in major depressive disorder, tic disorders and irritability associated with autism. It is taken by mouth or injection into a muscle. A Cochrane review found low-quality evidence of effectiveness in treating schizophrenia.

A dopamine antagonist, also known as an anti-dopaminergic and a dopamine receptor antagonist (DRA), is a type of drug which blocks dopamine receptors by receptor antagonism. Most antipsychotics are dopamine antagonists, and as such they have found use in treating schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and stimulant psychosis. Several other dopamine antagonists are antiemetics used in the treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Progabide is an analogue and prodrug of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) used in the treatment of epilepsy. Via conversion into GABA, progabide behaves as an agonist of the GABAA, GABAB, and GABAA-ρ receptors.

Amisulpride is an antiemetic and antipsychotic medication used at lower doses intravenously to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting; and at higher doses by mouth to treat schizophrenia and acute psychotic episodes. It is sold under the brand names Barhemsys and Solian, Socian, Deniban and others. At very low doses it is also used to treat dysthymia.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are symptoms that are archetypically associated with the extrapyramidal system of the brain's cerebral cortex. When such symptoms are caused by medications or other drugs, they are also known as extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE). The symptoms can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). They include movement dysfunction such as dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism characteristic symptoms such as rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, and tardive dyskinesia. Extrapyramidal symptoms are a reason why subjects drop out of clinical trials of antipsychotics; of the 213 (14.6%) subjects that dropped out of one of the largest clinical trials of antipsychotics, 58 (27.2%) of those discontinuations were due to EPS.

Bifeprunox (INN) (code name DU-127,090) is an atypical antipsychotic which, similarly to aripiprazole, combines minimal D2 receptor agonism with serotonin receptor agonism. It was under development for the treatment of schizophrenia but has since been abandoned.

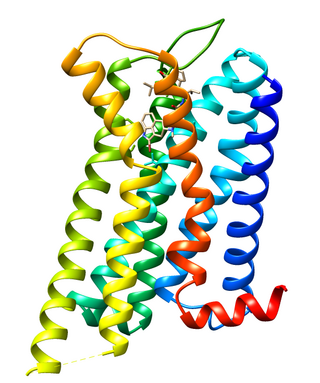

Dopamine receptor D2, also known as D2R, is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the DRD2 gene. After work from Paul Greengard's lab had suggested that dopamine receptors were the site of action of antipsychotic drugs, several groups, including those of Solomon Snyder and Philip Seeman used a radiolabeled antipsychotic drug to identify what is now known as the dopamine D2 receptor. The dopamine D2 receptor is the main receptor for most antipsychotic drugs. The structure of DRD2 in complex with the atypical antipsychotic risperidone has been determined.

The serotonin 1A receptor is a subtype of serotonin receptor, or 5-HT receptor, that binds serotonin, also known as 5-HT, a neurotransmitter. 5-HT1A is expressed in the brain, spleen, and neonatal kidney. It is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), coupled to the Gi protein, and its activation in the brain mediates hyperpolarisation and reduction of firing rate of the postsynaptic neuron. In humans, the serotonin 1A receptor is encoded by the HTR1A gene.

The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia models the subset of pathologic mechanisms of schizophrenia linked to glutamatergic signaling. The hypothesis was initially based on a set of clinical, neuropathological, and, later, genetic findings pointing at a hypofunction of glutamatergic signaling via NMDA receptors. While thought to be more proximal to the root causes of schizophrenia, it does not negate the dopamine hypothesis, and the two may be ultimately brought together by circuit-based models. The development of the hypothesis allowed for the integration of the GABAergic and oscillatory abnormalities into the converging disease model and made it possible to discover the causes of some disruptions.

Amperozide is an atypical antipsychotic of the diphenylbutylpiperazine class which acts as an antagonist at the 5-HT2A receptor. It does not block dopamine receptors as with most antipsychotic drugs, but does inhibit dopamine release, and alters the firing pattern of dopaminergic neurons. It was investigated for the treatment of schizophrenia in humans, but never adopted clinically. Its main use is instead in veterinary medicine, primarily in intensively farmed pigs, for decreasing aggression and stress and thereby increasing feeding and productivity.

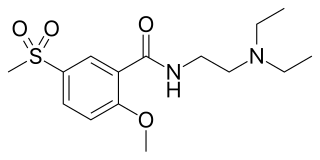

Tiapride is a drug that selectively blocks D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in the brain. It is used to treat a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders including dyskinesia, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, negative symptoms of psychosis, and agitation and aggression in the elderly. A derivative of benzamide, tiapride is chemically and functionally similar to other benzamide antipsychotics such as sulpiride and amisulpride known for their dopamine antagonist effects.

Blonanserin, sold under the brand name Lonasen, is a relatively new atypical antipsychotic commercialized by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma in Japan and Korea for the treatment of schizophrenia. Relative to many other antipsychotics, blonanserin has an improved tolerability profile, lacking side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, excessive sedation, or hypotension. As with many second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics it is significantly more efficacious in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to first-generation (typical) antipsychotics such as haloperidol.

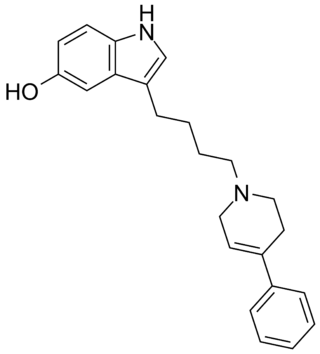

Roxindole (EMD-49,980) is a dopaminergic and serotonergic drug which was originally developed by Merck KGaA for the treatment of schizophrenia. In clinical trials its antipsychotic efficacy was only modest but it was unexpectedly found to produce potent and rapid antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. As a result, roxindole was further researched for the treatment of depression instead. It has also been investigated as a therapy for Parkinson's disease and prolactinoma.

Piquindone (Ro 22-1319) is an atypical antipsychotic with a tricyclic structure that was developed in the 1980s but was never marketed. It acts as a selective D2 receptor antagonist, though based on its effects profile its selectivity may be considered controversial. Unlike most other D2 receptor ligands, piquindone displays Na+-dependent binding, a property it shares with tropapride, zetidoline, and metoclopramide.

Cariprazine, sold under the brand names Vraylar and Reagila among others, is an atypical antipsychotic originated by Gedeon Richter, which is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania, bipolar depression, and major depressive disorder. It acts primarily as a D3 and D2 receptor partial agonist, with a preference for the D3 receptor. Cariprazine is also a partial agonist at the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor and acts as an antagonist at 5-HT2B and 5-HT2A receptors, with high selectivity for the D3 receptor. It is taken by mouth.

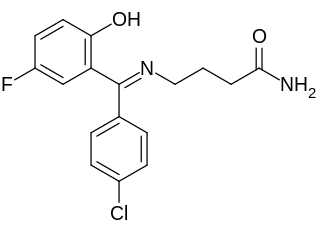

F-15,063 is an orally active potential antipsychotic, and an antagonist at the D2/D3 receptors, partial agonist at the D4 receptor, and agonist at the 5-HT1A receptors. It has greater efficacy at the 5-HT1A receptors than other antipsychotics, such as clozapine, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone. This greater efficacy may lead to enhanced antipsychotic properties, as antipsychotics that lack 5-HT1A affinity are associated with increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, and lack of activity against the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Brexpiprazole, sold under the brand name Rexulti among others, is an atypical antipsychotic. It is a dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist and has been described as a "serotonin–dopamine activity modulator" (SDAM). The drug was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 10 July 2015, for the treatment of schizophrenia, and as an adjunctive treatment for depression. It has been designed to provide improved efficacy and tolerability (e.g., less akathisia, restlessness and/or insomnia) over established adjunctive treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Brilaroxazine, also known as oxaripiprazole, is an investigational atypical antipsychotic which is under development by Reviva Pharmaceuticals for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Reviva Pharmaceuticals also intends to investigate brilaroxazine for the treatment of bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, psychosis/agitation associated with Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease psychosis, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD), and autism. As of August 2022, it is in phase III clinical trials for schizophrenia.

References

- ↑ Blomgren, Michael; Nagarajan, Srikantan S.; Lee, James N.; Li, Tianhao; Alvord, Lynn (2003). "Preliminary results of a functional MRI study of brain activation patterns in stuttering and nonstuttering speakers during a lexical access task". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 28 (4): 337–356. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2003.08.002. PMID 14643069.

- 1 2 Wu Joseph C.; Maguire, Gerald; Riley, Glyndon; Fallon, James; LaCasse, Lori; Chin, Sam; Klein, Eric; Tang, Cheuk; Cadwell, Stephanie; Lottenberg, Stephen (February 1995). "A positron emission tomography [18F]deoxyglucose study of developmental stuttering". NeuroReport. 6 (3): 501–505. doi:10.1097/00001756-199502000-00024. PMID 7766852.

- ↑ Blomgren, Michael; Nagarajan, Srikantan S.; Lee, James N.; Li, Tianhao; Alvord, Lynn (2003). "Preliminary results of a functional MRI study of brain activation patterns in stuttering and nonstuttering speakers during a lexical access task". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 28 (4): 337–356. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2003.08.002. PMID 14643069.

- ↑ Brady, J. P. (1991). "The pharmacology of stuttering: a critical review". American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (10): 1309–1316. doi:10.1176/ajp.148.10.1309. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 1680295.

- ↑ Mailman, Richard; Roth, Bryan L.; Sibley, David R.; Li-Xin Liu; Chiodo, Louis A.; Arrington, Elaine; Renock, Sean; Shapiro, David A. (August 2003). "Aripiprazole, A Novel Atypical Antipsychotic Drug with a Unique and Robust Pharmacology". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (8): 1400–1411. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203 . ISSN 1740-634X. PMID 12784105.

- ↑ Tran, Nancy L.; Maguire, Gerald A.; Franklin, David L.; Riley, Glyndon D. (August 2008). "Case Report of Aripiprazole for Persistent Developmental Stuttering". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (4): 470–472. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31817ea9ad. ISSN 0271-0749. PMID 18626285.

- ↑ Carson, William H.; Kitagawa, Hisashi (2004). "Drug development for anxiety disorders: new roles for atypical antipsychotics". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 38 (1): 38–45. ISSN 0048-5764. PMID 15278017.

- ↑ Murphy, Ruth; Gallagher, Anne; Sharma, Kapil; Ali, Tariq; Lewis, Elizabeth; Murray, Ivan; Hallahan, Brian (August 2015). "Clozapine-induced stuttering: an estimate of prevalence in the west of Ireland". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 5 (4): 232–236. doi:10.1177/2045125315590060. ISSN 2045-1253. PMC 4535049 . PMID 26301079.

- ↑ Yoo, Hanik K.; Lee, Joong-Sun; Paik, Kyoung-Won; Choi, Soon-Ho; Yoon, Sujung J.; Kim, Jieun E.; Hong, Jin Pyo (March 2011). "Open-label study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole and haloperidol in the treatment of pediatric tic disorders". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 20 (3): 127–135. doi:10.1007/s00787-010-0154-0. ISSN 1018-8827. PMC 3046348 . PMID 21188439.