The Umayyad Caliphate was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. The third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, Uthman ibn Affan, was also a member of the Umayyad clan. The family established dynastic, hereditary rule with Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, long-time governor of al-Sham, who became the sixth caliph after the end of the First Fitna in 661. After Mu'awiyah's death in 680, conflicts over the succession resulted in the Second Fitna, and power eventually fell into the hands of Marwan I from another branch of the clan. The region of Syria remained the Umayyads' main power base thereafter, and Damascus was their capital.

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam was the fifth Umayyad caliph, ruling from April 685 until his death. A member of the first generation of born Muslims, his early life in Medina was occupied with pious pursuits. He held administrative and military posts under Caliph Mu'awiya I, founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, and his own father, Caliph Marwan I. By the time of Abd al-Malik's accession, Umayyad authority had collapsed across the Caliphate as a result of the Second Muslim Civil War and had been reconstituted in Syria and Egypt during his father's reign.

Edessa was an ancient city (polis) in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator, founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene, and continued as capital of the Roman province of Osroene. During the Late Antiquity, it became a prominent center of Christian learning and seat of the Catechetical School of Edessa. During the Crusades, it was the capital of the County of Edessa.

Yazid ibn Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, commonly known as Yazid I, was the second caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate. He ruled from April 680 until his death in November 683. His appointment was the first hereditary succession to the caliphate in Islamic history. His caliphate was marked by the death of Muhammad's grandson Husayn ibn Ali and the start of the crisis known as the Second Fitna.

Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn al-Ḥakam ibn ʿAqīl al-Thaqafī, known simply as al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, was probably the most notable governor who served the Umayyad Caliphate. He began his service with the Umayyads under Caliph Abd al-Malik, who successively promoted him as the head of the caliph's shurta, the governor of the Hejaz in 692–694, and the practical viceroy of a unified Iraqi province and the eastern parts of the Caliphate in 694. Al-Hajjaj retained the last post under Abd al-Malik's son and successor al-Walid I, whose decision-making was highly influenced by al-Hajjaj, until his death in 714.

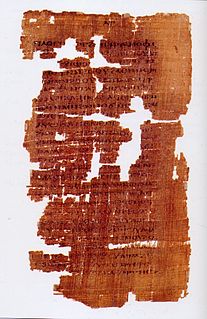

Written in Syriac in the late seventh century, the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius shaped and influenced Christian eschatological thinking in the Middle Ages. Falsely attributed to Methodius of Olympus, a fourth century Church Father, the work attempts to make sense of the Islamic conquest of the Near East. The Apocalypse is noted for incorporating numerous aspects of Christian eschatology such as the invasion of Gog and Magog, the rise of the Antichrist, and the tribulations that precede the end of the world.

The West Syriac Rite, also called Syro-Antiochene Rite, is an Eastern Christian liturgical rite that employs the Divine Liturgy of Saint James in the West Syriac dialect. It is practised in the Maronite Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church and various Malankara Churches of India. It is one of two main liturgical rites of Syriac Christianity, the other being the East Syriac Rite.

Hagarenes, is a term widely used by early Syriac, Greek, Coptic and Armenian sources to describe the early Arab conquerors of Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

Safiyya bint Abd al-Muttalib was a companion and aunt of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam from the Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam series is a book by scholar of the Middle East Robert G. Hoyland.

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad caliphate. It followed the death of the first Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I in 680 and lasted for about twelve years. The war involved the suppression of two challenges to the Umayyad dynasty, the first by Husayn ibn Ali, as well as his supporters including Sulayman ibn Surad and Mukhtar al-Thaqafi who rallied for his revenge in Iraq, and the second by Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.

Bahira was an assyrian-arameic Nestorian or possibly Gnostic Nasorean monk who, according to Islamic tradition, foretold to the adolescent Muhammad his future as a prophet. His name derives from the Syriac bḥīrā, meaning “tested and approved”.

Abū Unaysal-Ḍaḥḥak ibn Qays al-Fihrī was an Umayyad general, head of security forces and governor of Damascus during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I, Yazid I and Mu'awiya II. Though long an Umayyad loyalist, after the latter's death, al-Dahhak defected to the anti-Umayyad claimant to the caliphate, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.

Qenneshre was a large West Syriac monastery between the 6th and 13th centuries. It was a centre for the study of ancient Greek literature and the Greek Fathers, and through its Syriac translations it transmitted Greek works to the Islamic world. It was "the most important intellectual centre of the Syriac Orthodox ... from the 6th to the early 9th century", when it was sacked and went into decline.

The Apocalypse of John the Little is an apocalyptic text supposedly given to John the Apostle by revelation. It is dated to the eighth-century AD and pertains to the rise of Islam. The title includes "the Little" which is in reference to John being the younger brother of James the Great. The text models itself from that of the Book of Revelation and the Book of Daniel and provides some of the cruelest surviving Syriac representations of Islamic dominance. It is also one of the earliest text alluding to Muhammad by Christians and possibly one of the earliest accounts of Christians converting to Islam.

The Book of Main Points is a chronicle text about the world's history from the creation of the world to the late seventh century. It was written in the 680s, and was authored by the monk John of Fenek at the request of the abbot of East Syrian monastery of John Kāmul. The text is regarded as an important historical source for understanding the military and political events of the 680s and understanding the rise of Islam. John of Fenek is an eyewitness to many of the events occurring in his work. He also presents an East Syrian theological response to the Islamic conquest and documents the rise of Christian apocalyptic expectations that define Syriac writings of the late seventh century.

The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Athanasius is an apocalyptic sermon authored between 715 and 744 during the Umayyad Caliphate. Very popular, the work was found in multiple Coptic manuscripts and in Arabic translations. The text most likely served as an influence for both Coptic and Coptic-Arabic writings and is also a rare witness to the reaction of Copts towards the Muslim conquest of Egypt. Though Islamic practices of faith are absent from the text, it still provides the author's Coptic perspective to the fundamental historic changes in their country and the everyday-lives of the inhabitants.

The Apocalypse of Shenute is a short Coptic apocalyptic text which purports to be a prophecy of Shenute from Christ about the eschaton. The Coptic Apocalypse of Elijah greatly influenced the text. It is the oldest miaphysite Coptic apocalypse to survive from the Islamic period, a rare contemporary witness to Coptic–Muslim relations in the earliest period, one of the earliest miaphysite Coptic sources to mention the Islamic rejection of the crucifixion of Christ, and a response to the Islamic conversion of Copts.

The Gospel of the Twelve Apostles is a gospel text that summarizes the four canonical gospels and the beginning of the Acts of the Apostles followed by three apocalypses. It survives only in a single manuscript and is inspired by the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius. Its eschatological expectations was both simple and updated from previous Syriac apocalyptical texts of the same period and is a witness to the Syrian Christian strategy on coping with Muslim rule in the second half of the seventh century as the Muslim rule was no longer being perceived as a temporary event causing apocalyptic tensions to dissipate. It also advocates disconnection from Judaism and non-Miaphysite and presents the author's advocacy in their own community to not have them convert to Islam but have the community keep the true faith.

Job of Edessa, called the Spotted, was a Christian natural philosopher and physician active in Baghdad and Khurāsān under the Abbasid Caliphate. He played an important role in transmitting Greek science to the Islamic world through his translations into Syriac.