Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begins in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years; some can be found in the Yi Jing, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE. It was during the Warring States era that what Sima Tan termed the major philosophical schools of China: Confucianism, Legalism, and Taoism, arose, along with philosophies that later fell into obscurity, like Agriculturalism, Mohism, Chinese Naturalism, and the Logicians.

New Confucianism is an intellectual movement of Confucianism that began in the early 20th century in Republican China, and further developed in post-Mao era contemporary China. It is deeply influenced by, but not identical with, the neo-Confucianism of the Song and Ming dynasties. It is a neo-conservative movement of various Chinese traditions and has been regarded as containing religious overtones; it advocates for certain Confucianist elements of society – such social, ecological, and political harmony – to be applied in a contemporary context in synthesis with Western philosophies such as rationalism and humanism. Its philosophies have emerged as a focal point of discussion between Confucian scholars in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States.

Tokugawa Ienobu was the sixth shōgun of the Tokugawa dynasty of Japan. He was the eldest son of Tokugawa Tsunashige, thus making him the nephew of Tokugawa Ietsuna and Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the grandson of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the great-grandson of Tokugawa Hidetada, and the great-great grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu. All of Ienobu's children died young.

Wang Shouren, courtesy name Bo'an, was a Chinese idealist Neo-Confucian philosopher, official, educationist, calligraphist and general during the Ming dynasty. After Zhu Xi, he is commonly regarded as the most important Neo-Confucian thinker, with interpretations of Confucianism that denied the rationalist dualism of the orthodox philosophy of Zhu Xi. Wang was known as Yangming Xiansheng and/or Yangming Zi in literary circles: both mean "Master Yangming".

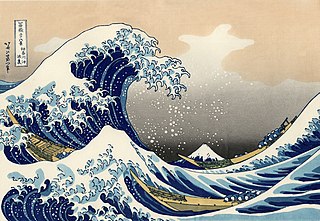

Japanese philosophy has historically been a fusion of both indigenous Shinto and continental religions, such as Buddhism and Confucianism. Formerly heavily influenced by both Chinese philosophy and Indian philosophy, as with Mitogaku and Zen, much modern Japanese philosophy is now also influenced by Western philosophy.

Korean philosophy focused on a totality of world view. Some aspects of Shamanism, Buddhism, and Neo-Confucianism were integrated into Korean philosophy. Traditional Korean thought has been influenced by a number of religious and philosophical thought-systems over the years. As the main influences on life in Korea, often Korean Shamanism, Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism and Silhak movements have shaped Korean life and thought.

Yushima Seidō, located in the Yushima neighbourhood of Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan, was established as a Confucian temple in the Genroku era of the Edo period.

Buddhism has interacted with several East Asian religions such as Confucianism and Shintoism since it spread from India during the 2nd century AD.

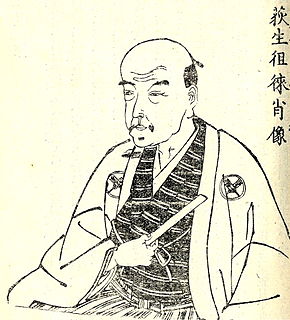

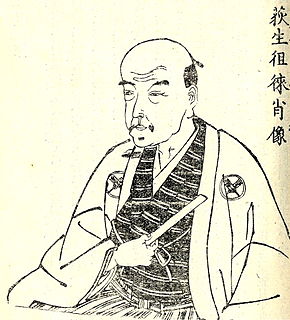

Ogyū Sorai, pen name Butsu Sorai, was a Japanese Confucian philosopher. He has been described as the most influential such scholar during the Tokugawa period. His primary area of study was in applying the teachings of Confucianism to government and social order. He responded to contemporary economic and political failings in Japan, as well as the culture of mercantilism and the dominance of old institutions that had become weak with extravagance. Sorai rejected the moralism of Song Confucianism and instead looked to the ancient works. He argued that allowing emotions to be expressed was important and nurtured Chinese literature in Japan for this reason. Sorai attracted a large following with his teachings and created the Sorai school, which would become an influential force in further Confucian scholarship in Japan.

The Hayashi clan was a Japanese samurai clan which served as important advisors to the Tokugawa shōguns. Among members of the clan in powerful positions in the shogunate was its founder Hayashi Razan, who passed on his post as hereditary rector of the neo-Confucianist Shōhei-kō school to his son, Hayashi Gahō, who also passed it on to his son, Hayashi Hōkō; this line of descent continued until the end of Hayashi Gakusai's tenure in 1867. However, elements of the school carried on until 1888, when it was folded into the newly organized Tokyo University.

Hayashi Jussai was a Japanese neo-Confucian scholar of the Edo period. He was an hereditary rector of Edo’s Confucian Academy, the Shōhei-kō, also known at the Yushima Seidō, which was built on land provided by the shōgun. The Yushima-Seidō, which stood at the apex of the Tokugawa shogunate's educational system; and Jussai was styled with the hereditary title "Head of the State University".

Hayashi Hōkō, also known as Hayashi Nobutatsu, was a Japanese Neo-Confucian scholar, teacher and administrator in the system of higher education maintained by the Tokugawa bakufu during the Edo period. He was a member of the Hayashi clan of Confucian scholars.

This is a list of articles in Eastern philosophy.

Yoshida Shintō (吉田神道) also frequently referred to as Yuiitsu Shintō was a prominent sect of Shintō that arose during the Sengoku period through the teachings and work of Yoshida Kanetomo. The sect was originally an effort to organize Shintō teachings into a coherent structure in order to assert its authority vis-a-vis Buddhism. However, by the Edo period, Yoshida Shintō continued to dominate the Shintō discourse, and influenced Neo-Confucian thinkers such as Hayashi Razan and Yamazaki Ansai in formulating a Neo-Confucian Shinto doctrine. Yoshida Shinto's dominance rivaled that of Ise Shintō.