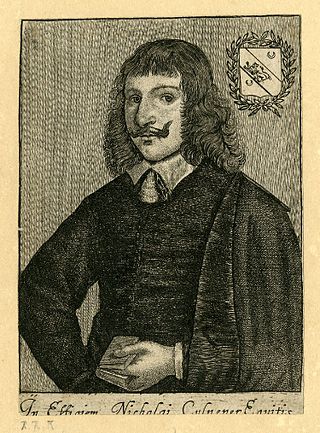

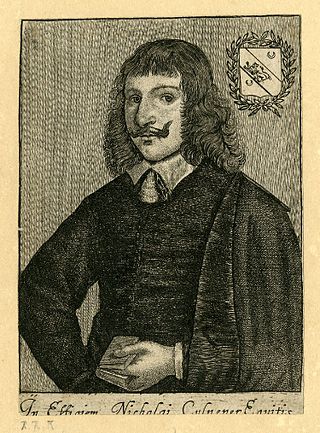

Nicholas Culpeper was an English botanist, herbalist, physician and astrologer. His book The English Physitian is a source of pharmaceutical and herbal lore of the time, and Astrological Judgement of Diseases from the Decumbiture of the Sick (1655) one of the most detailed works on medical astrology in Early Modern Europe. Culpeper catalogued hundreds of outdoor medicinal herbs. He scolded contemporaries for some of the methods they used in herbal medicine: "This not being pleasing, and less profitable to me, I consulted with my two brothers, Dr. Reason and Dr. Experience, and took a voyage to visit my mother Nature, by whose advice, together with the help of Dr. Diligence, I at last obtained my desire; and, being warned by Mr. Honesty, a stranger in our days, to publish it to the world, I have done it."

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or magical powers, and the legends associated with them. A herbal may also classify the plants it describes, may give recipes for herbal extracts, tinctures, or potions, and sometimes include mineral and animal medicaments in addition to those obtained from plants. Herbals were often illustrated to assist plant identification.

Artemisia Lomi or Artemisia Gentileschi was an Italian Baroque painter. Gentileschi is considered among the most accomplished seventeenth-century artists, initially working in the style of Caravaggio. She was producing professional work by the age of 15. In an era when women had few opportunities to pursue artistic training or work as professional artists, Gentileschi was the first woman to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence and she had an international clientele.

Elizabeth Carter was an English poet, classicist, writer, translator, linguist, and polymath. As one of the Bluestocking Circle that surrounded Elizabeth Montagu, she earned respect for the first English translation of the 2nd-century Discourses of Epictetus. She also published poems and translated from French and Italian, and corresponded profusely. Among her many eminent friends were Elizabeth Montagu, Hannah More, Hester Chapone and other Bluestocking members. Also close friends were Anne Hunter, a poet and socialite, and Mary Delany. She befriended Samuel Johnson, editing some editions of his periodical The Rambler.

Carol Patrice Christ was a feminist historian, thealogian, author, and foremother of the Goddess movement. She obtained her PhD from Yale University and served as a professor at universities such as Columbia University and Harvard Divinity School. Her best-known publication is "Why Women Need The Goddess". It was initially a keynote presentation at the "Great Goddess Re-emerging" conference" at the University of Santa Cruz in 1978. This essay helped to launch the Goddess movement in the U.S. and other countries. It discusses the importance of religious symbols in general, and the effects of male symbolism of God on women in particular. Christ called herself a "thealogian" and as such, made important contributions to the discipline of theology, significantly helping to create a space for it to be far more inclusive of women than has historically been the case. The term "thealogy" is derived from Ancient Greek θεά + -logy .

Martha Moore Ballard was an American midwife and healer. Unusual for the time, Ballard kept a diary with thousands of entries over nearly three decades, which has provided historians with invaluable insight into frontier-women's lives. Ballard was made famous by the publication of A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard based on her diary, 1785–1812 by historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich in 1990.

William Randolph I was an English-born planter, merchant and politician in colonial Virginia who played an important role in the development of the colony. Born in Moreton Morrell, Warwickshire, Randolph moved to the colony of Virginia sometime between 1669 and 1673, and married Mary Isham a few years later. His descendants include many prominent individuals including Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, Paschal Beverly Randolph, Robert E. Lee, Peyton Randolph, Edmund Randolph, John Randolph of Roanoke, George W. Randolph, and Edmund Ruffin. Due to his and Mary's many progeny and marital alliances, they have been referred to as "the Adam and Eve of Virginia".

Hilda Leyel, who wrote under the name Mrs. C. F. Leyel, was an expert on herbalism and founded the Society of Herbalists in England in 1927, as well as a chain of herbalist stores called the Culpeper House herb shops.

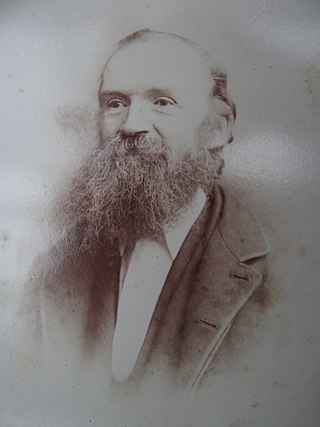

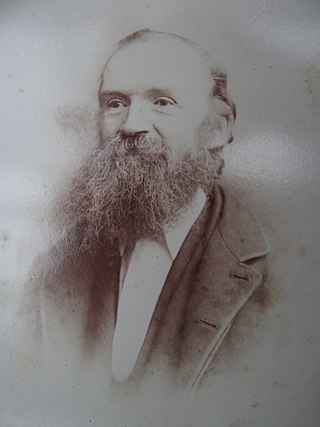

Duncan Scott Napier was a Scottish botanist, herbalist and businessman. Despite having a deprived childhood and being functionally illiterate until his early teens, he became an expert in herbal remedies and did much to establish herbalism as a recognised branch of medicine. The herbalist business that he founded stayed in his family for three generations and still exists today.

Elizabeth Blackwell was a botanical illustrator and author who was best known as both the artist and engraver for the plates of "A Curious Herbal", published between 1737 and 1739. The book illustrated medicinal plants, and was designed as a reference work for the use of physicians and apothecaries.

Sir Justinian Isham, 2nd Baronet was an English scholar and royalist politician. He was also a Member of Parliament and an early member of the Royal Society.

Mary Rich, Countess of Warwick was the seventh daughter of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, and his second wife, Catherine Fenton, only daughter of Sir Geoffrey Fenton, Principal Secretary of State for Ireland, and Alice Weston. She was born in 1625 in Youghal, County Cork, and after her mother's death in 1628, was raised by her relatives Sir Richard and Lady Clayton in Mallow, before becoming a maid of honour to Queen Henrietta Maria. In 1641 she married Charles Rich, 4th Earl of Warwick. They had two children, who died young. Rich is remembered for her love of literature and the diaries she kept from 1666 to 1677, which include many of the current events in 17th-century Ireland, alongside her domestic issues.

Joan Carlile or Carlell or Carliell, was an English portrait painter. She was one of the first British women known to practise painting professionally. Before Carlile, known professional female painters working in Britain were born elsewhere in Europe, principally the Low Countries.

Sir John Isham Bt (1582-1651) was High Sheriff of Northamptonshire and created the 1st hereditary Baronet of Lamport by King Charles I.

The history of herbalism is closely tied with the history of medicine from prehistoric times up until the development of the germ theory of disease in the 19th century. Modern medicine from the 19th century to today has been based on evidence gathered using the scientific method. Evidence-based use of pharmaceutical drugs, often derived from medicinal plants, has largely replaced herbal treatments in modern health care. However, many people continue to employ various forms of traditional or alternative medicine. These systems often have a significant herbal component. The history of herbalism also overlaps with food history, as many of the herbs and spices historically used by humans to season food yield useful medicinal compounds, and use of spices with antimicrobial activity in cooking is part of an ancient response to the threat of food-borne pathogens.

Elizabeth Walker was a British druggist known for her charity and piety. She kept a journal which was published and commented on posthumously by her husband, Anthony Walker, entitled, “The vertuous wife: or, the holy life of Mrs. Elizabeth Walker, late wife of A. Walker, D.D. sometime Rector of Fyfield in Essex: Giving a modest and short account of her exemplary piety and charity. Published for the glory of God, and provoking others to the like graces and vertues. With some useful papers and letters writ by her on several occasions.”

Rebecca Dickinson was an American gownmaker who lived during the mid-to-late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century. She is significant as the author of a journal in which she writes about her life as an artisan in the context of a woman actively engaging in the economy and a Calvinist in New England in the years following the Revolutionary War (1787-1802). Throughout her life, Dickinson chose to live as a single woman in Hatfield, Massachusetts, sustaining herself through her trade. Her surviving journal documents her struggle to understand her singlehood in the context of her faith. Her diary also allows a glimpse into the lives of people, especially women, living through extremely influential historical events.

Anne Cary was a British Benedictine nun who founded 'Our Lady of Good Hope Convent' in Paris.

Anne Venn was an English religious radical and diarist. Her diaries document her worry that she was damned. She found some relief in 1652 and she gave substantial legacies to the church in Fulham.

Teresa Mulally was an Irish educationist, businesswoman, and philanthropist.