The Underground Railroad was used by freedom seekers from slavery in the United States and was generally an organized network of secret routes and safe houses. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery as early as the 16th century and many of their escapes were unaided, but the network of safe houses operated by agents generally known as the Underground Railroad began to organize in the 1780s among Abolitionist Societies in the North. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln. The escapees sought primarily to escape into free states, and from there to Canada.

Thomas Garrett was an American abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. He helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

Africa is an unincorporated community located in Orange Township of southern Delaware County, Ohio, United States, by Alum Creek.

Daniel Hughes (1804–1880) was a conductor, agent and station master in the Underground Railroad based in Loyalsock Township, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania in the United States. He was the owner of a barge on the Pennsylvania Canal and transported lumber from Williamsport on the West Branch Susquehanna River to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Hughes hid runaway slaves in the hold of his barge on his return trip up the Susquehanna River to Lycoming County, where he provided shelter to the runaways on his property near the Loyalsock Township border with Williamsport before they moved further north and to eventual freedom in Canada. Hughes' home was located in a hollow or small valley in the mountains just north of Williamsport. This hollow is now known as Freedom Road, having previously been called Nigger Hollow. In response to the actions of concerned African American citizens of Williamsport, the pejorative name was formally changed by the Williamsport City Council in 1936.

The John Freeman Walls Historic Site and Underground Railroad Museum is a 20-acre (81,000 m2) historical site located in Puce, now Lakeshore, Ontario, about 40 km east of Windsor. Today, many of the original buildings remain, and in 1985, the site was opened as an Underground Railroad museum. The site forms part of the African-Canadian Heritage Tour in Southern Ontario.

The John Johnson House is a National Historic Landmark in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, significant for its role in the antislavery movement and the Underground Railroad. It is located at 6306 Germantown Avenue and is a contributing property of the Colonial Germantown Historic District, which is also a National Historic Landmark. It is operated today as a museum open to the public.

The Underground Railroad in Indiana was part of a larger, unofficial, and loosely-connected network of groups and individuals who aided and facilitated the escape of runaway slaves from the southern United States. The network in Indiana gradually evolved in the 1830s and 1840s, reached its peak during the 1850s, and continued until slavery was abolished throughout the United States at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It is not known how many fugitive slaves escaped through Indiana on their journey to Michigan and Canada. An unknown number of Indiana's abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and people of color, as well as Quakers and other religious groups illegally operated stations along the network. Some of the network's operatives have been identified, including Levi Coffin, the best-known of Indiana's Underground Railroad leaders. In addition to shelter, network agents provided food, guidance, and, in some cases, transportation to aid the runaways.

Lemmon v. New York, or Lemmon v. The People (1860), popularly known as the Lemmon Slave Case, was a freedom suit initiated in 1852 by a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. The petition was granted by the Superior Court in New York City, a decision upheld by the New York Court of Appeals, New York's highest court, in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War.

The Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall is a group of historic buildings which are located in Plymouth Meeting, Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. In the decades prior to the American Civil War, this property served as an important station on the Underground Railroad. Abolition Hall was built to be a meeting place for abolitionists, and later was the studio of artist Thomas Hovenden.

The History of slavery in Michigan includes the pro-slavery and anti-slavery efforts of the state's residents prior to the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

George DeBaptiste was a prominent African-American conductor on the Underground Railroad in southern Indiana and Detroit, Michigan. Born free in Virginia, he moved as a young man to the free state of Indiana. In 1840, he served as valet and then White House steward for US President William Henry Harrison, who was from that state. In the 1830s and 1840s DeBaptiste was an active conductor on the underground railroad in Madison, Indiana. Located along the Ohio River across from Kentucky, a slave state, this town was a destination for refugee slaves seeking escape from slavery.

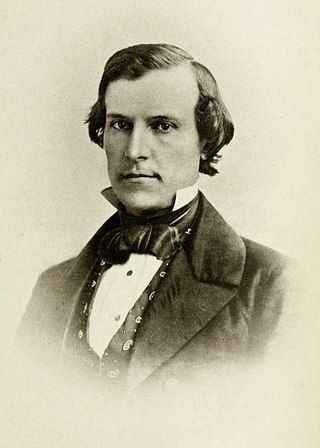

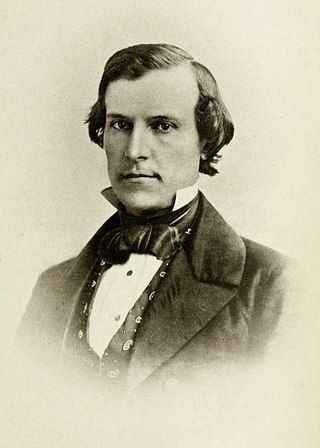

George Hussey Earle Sr. was a prominent Philadelphia lawyer. As an abolitionist, he represented many fugitive slaves. He was a founder of the Republican party.

Merlin Mead was an Underground Railroad conductor and station master, one of several people from the hamlet of Cadiz within Franklinville, New York that sheltered and aided enslaved people who escaped and headed for freedom in Canada. He was a farmer, schoolmaster, town clerk, postmaster, and justice of the peace. He operated a public house, until he attended a temperance meeting and stopped selling liquor. Mead was ordained an elder and was an active leader of the First Presbyterian Church in Franklinville.

Kentucky raid in Cass County (1847) was conducted by slaveholders and slave catchers who raided Underground Railroad stations in Cass County, Michigan to capture black people and return them to slavery. After unsuccessful attempts, and a lost court case, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was enacted. Michigan's Personal Liberty Act of 1855 was passed in the state legislature to prevent the capture of formerly enslaved people that would return them to slavery.

Wright Modlin or Wright Maudlin (1797–1866) helped enslaved people escape slavery, whether transporting them between Underground Railroad stations or traveling south to find people that he could deliver directly to Michigan. Modlin and his Underground Railroad partner, William Holden Jones, traveled to the Ohio River and into Kentucky to assist enslave people on their journey north. Due to their success, angry slaveholders instigated the Kentucky raid on Cass County of 1847. Two years later, he helped free his neighbors, the David and Lucy Powell family, who had been captured by their former slaveholder. Tried in South Bend, Indiana, the case was called The South Bend Fugitive Slave Case.

Adam Crosswhite (1799–1878) was a former slave who fled slavery along the Underground Railroad and settled in Marshall, Michigan. In 1847, slavers from Kentucky came to Michigan to kidnap African Americans and return them to slavery in Kentucky. Citizens of the town surrounded the Crosswhite's house and prevented them from being abducted. The Crosswhites fled to Canada, and their former enslaver, Francis Giltner, filed a suit, Giltner vs. Gorham et al., against residents of Marshall. Giltner won the case and was compensated for the loss of the Crosswhite family. After the Civil War, Crosswhite returned to Marshall, where he lived the rest of his life.

Guy Beckley (1803–1847) was a Methodist Episcopal minister, abolitionist, Underground Railroad stationmaster, and lecturer. The Guy Beckley House is on the National Park Service Underground Railroad Network to Freedom and the Journey to Freedom tour. It stands next to Beckley Park, which was named after him.

Lyman Goodnow (1799–1884), a resident of Waukesha, Wisconsin, was a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Eusebius Barnard was an American farmer and station master on the Underground Railroad in Chester County, Pennsylvania, helping hundreds of fugitive slaves escape to freedom. A minister of the Progressive Friends and founding member of Longwood Meeting House, Barnard championed women’s rights, temperance, and abolition of slavery. A Pennsylvania state historical marker was placed outside his home in Pocopson Township on April 30, 2011.