Early life and education

Kitzinger [1] was born into a well-educated Jewish family in Munich; his father, Wilhelm Nathan Kitzinger, was a prominent lawyer; his mother, Elisabeth Kitzinger, née Merzbacher, was a pioneering social worker involved with child welfare among Eastern European Jewish refugee and immigrant families. Kitzinger entered the University of Munich in 1931, where he studied the history of art, principally under Wilhelm Pinder. From the summer of 1931 on, Kitzinger spent significant time in Rome, enrolled in the University of Rome and intellectually centered at the Bibliotheca Hertziana. (Kitzinger's distant relation, Richard Krautheimer [1897–1994], who also became a major art historian, of late antique and Byzantine architecture, was coincidentally doing research at the Hertziana at the same time.) The beginning of the Nazi regime in 1933 raised the immediate possibility that Jewish students might be banned from receiving degrees. Kitzinger accordingly completed his dissertation, a brief but influential study of Roman painting in the 7th and 8th centuries, with exceptional speed, and defended it in the fall of 1934. He left Germany the day after his thesis defense.

Kitzinger first returned to Rome, before moving on to England, where he found volunteer employment at the British Museum while eking out a living doing casual academic work, writing book reviews, and receiving the occasional small grant. Among a wide range of art historical interests, he quickly developed a particular focus on Anglo-Saxon art through being enlisted by T. D. Kendrick to assist in a comprehensive survey of surviving pre-Norman stone sculpture in England. Kitzinger's first published article was on Anglo-Saxon vinescroll ornament; he also contributed to the assessment of the treasures of the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial as it was unearthed over months in 1939. In 1937, on a modest grant from a patron of the British Museum, he travelled to Egypt and Istanbul, further widening his perspective on late antique and early medieval art as an "international" phenomenon. It was this perspective that he brought to his first book, Early Medieval Art in the British Museum (1940). Ostensibly a guidebook, this was in fact an attempt to trace the transformation of classical art into medieval, a subject which Kitzinger would revisit on many occasions throughout his career. The book has never gone out of print; more recent editions are just called Early Medieval Art.

World War II

Kitzinger, although he had left Germany because he was Jewish, was interned in 1940 as an "enemy alien" (having German nationality and background) with many others in similar circumstances. He was transported to Australia in a perilous and fraught sea voyage on HMT Dunera. Though he received an official release immediately upon arrival at an internment camp in Hay, New South Wales (through the intervention of the Warburg Institute), he was stranded there for nine months. He did succeed in putting the time on the voyage and in the camp to valuable use, though, acquiring a working knowledge of Russian from a fellow internee.

Academic career

In 1941 Kitzinger managed, with some difficulty, to travel to Washington, D.C., where he became a Junior Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks, which had in 1940 been donated as a research library to Harvard University. Once there, Kitzinger was assigned by Wilhelm Koehler to a systematic study of the Byzantine monuments of the Balkans (leading to an important article on the monuments of Stobi in 1946). Several years later, after a wartime stint with the OSS in Washington, London, and eventually Paris, Kitzinger began work on a complete survey of the mosaics of Norman Sicily. This project would occupy him for the rest of his life, resulting first in The Mosaics of the Capella Palatina in Palermo: An Essay on the Choice and Arrangement of Subjects [Art Bulletin 31 (1949): 269–292] and The Mosaics of Monreale [Palermo: S. F. Flaccovio Editore (1960) (republished, 1991, with a new preface, Italian only)] and later in The Mosaics of St. Mary's of the Admiral in Palermo [Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Studies (1990)] and the publication of a six-volume corpus of photographs of the mosaics, I mosaici del periodo normanno in Sicilia (1992–1995).

Kitzinger quickly advanced through the ranks at Dumbarton Oaks, becoming an Assistant Professor in 1946, Associate Professor in 1951, Director of Studies in 1955, and Professor of Byzantine Art and Archaeology in 1956. As Director of Studies he firmly established Dumbarton Oaks as an academic institution of international renown and the world's leading institution for Byzantine studies.

Kitzinger resigned as director of studies at Dumbarton Oaks in 1966, in part to rebalance his work as a scholar after eleven years of heavy administrative duties. During those years, he had occasionally taught courses at Harvard's Cambridge campus, and in 1967, after an interlude at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, he moved to Harvard permanently, accepting a position as the Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor, which he held until his retirement in 1979. At Harvard Kitzinger supervised eighteen doctoral dissertations. Among his distinguished students over his years of teaching and mentoring are Hans Belting, Madeline Caviness, Joseph Connors, Anna Gonosova, Christine Kondoleon, Irving Lavin, Henry Maguire, John Mitchell, Lawrence Nees, Nancy Netzer, Natasha Staller, James Trilling, Rebecca Corrie, and William Tronzo.

The major theoretical contributions of Kitzinger's later career are embodied in his book Byzantine art in the making (1977), which is based on the Slade Lectures he delivered at the University of Cambridge in 1974–1975, and in two collections of essays: a single volume published by Indiana U. Press in 1976 as The Art of Byzantium and the Medieval West, and a two-volume set edited by John Mitchell and published by Pindar Press in 2002 and 2004: Studies in Late Antique, Byzantine and Medieval Western Art. Kitzinger maintained his lifelong preoccupation with the analysis of style change in late antique and early medieval art, and his conviction that stylistic analysis could speak with an authority equal to that of iconography or textual history. To this end he developed a theory of "modes," according to which certain styles were appropriate to the depiction of certain subjects. In Byzantine art in the making, furthermore, he essayed a bold attempt to trace the stylistic "dialectic" of the period in question:

At certain times and in certain places bold stabs were made in the direction of new, unclassical forms, only to be followed by reactions, retrospective movements and revivals. In some contexts such developments - in either direction - took place slowly, hestitantly, and by steps so small as to be almost imperceptible. In addition there were extraordinary attempts at synthesis, at reconciling conflicting aesthetic ideals. Out of this complex dialectic, medieval form emerged. [2]

The totality of Kitzinger's work was enormously influential in making Byzantine art a field of art historical study. And, though art historical methodology based on stylistic analysis largely fell out of fashion in the 1980s and 1990s, and Byzantine Art in the Making has been described as the last gasp of Viennese-style formalist art history on the model of Aloïs Riegl and Josef Strzygowski]., [3] many aspects of Kitzinger's methodology may be described as prescient. Kitzinger anticipated contemporary concerns of the field in his emphasis on the centrality of art to cult in much-cited works such as "The Cult of Images in the Age Before Iconoclasm" (1954); in his interest in questions of meaning in ornament (e.g., "Interlace and Icons" [1993]) and significance in the position of images (e.g., "A Pair of Silver Bookcovers in the Sion Treasure" [1974]); and in his sustained work on the relationship between art of the Greek and Latin worlds. Furthermore, it has been argued that "when the pendulum of fashion swings back again, [Kitzinger's] works will undoubtedly be central to a reconsideration of style.". [4]

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly popular in the Ancient Roman world.

The Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark, commonly known as St Mark's Basilica, is the cathedral church of the Patriarchate of Venice; it became the episcopal seat of the Patriarch of Venice in 1807, replacing the earlier cathedral of San Pietro di Castello. It is dedicated to and holds the relics of Saint Mark the Evangelist, the patron saint of the city.

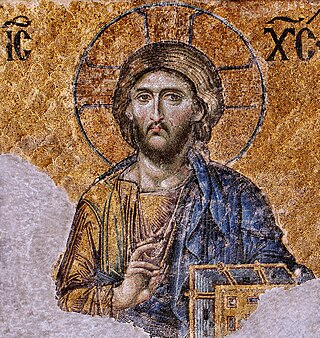

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

The Quedlinburg Itala fragment is a fragment of six folios from a large 5th-century illuminated manuscript of an Old Latin Itala translation of parts of 1 Samuel of the Old Testament. It was probably produced in Rome in the 420s or 430s. It is the oldest surviving illustrated biblical manuscript and has been in the Berlin State Library since 1875-76. The pages are approximately 305 x 205 mm large.

Cosmatesque, or Cosmati, is a style of geometric decorative inlay stonework typical of the architecture of Medieval Italy, and especially of Rome and its surroundings. It was used most extensively for the decoration of church floors, but was also used to decorate church walls, pulpits, and bishop's thrones. The name derives from the Cosmati, the leading family workshop of craftsmen in Rome who created such geometrical marble decorations.

The Palazzo dei Normanni is also called Royal Palace of Palermo. It was the seat of the Kings of Sicily with the Hauteville dynasty and served afterwards as the main seat of power for the subsequent rulers of Sicily. Since 1946 it has been the seat of the Sicilian Regional Assembly. The building is the oldest royal residence in Europe; and was the private residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Sicily and the imperial seat of Frederick II and Conrad IV.

Monreale Cathedral is a Catholic church in Monreale, Metropolitan City of Palermo, Sicily. One of the greatest existent examples of Norman architecture, it was begun in 1174 by William II of Sicily. In 1182 the church, dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, was, by a bull of Pope Lucius III, elevated to the rank of a metropolitan cathedral as the seat of the diocese of Monreale, which was elevated to the Archdiocese of Monreale in 1183. Since 2015 it has been part of the Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Spolia are stones taken from an old structure and repurposed for new construction or decorative purposes. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice (spoliation) whereby stone that has been quarried, cut and used in a built structure is carried away to be used elsewhere. The practice is of particular interest to historians, archaeologists and architectural historians since the gravestones, monuments and architectural fragments of antiquity are frequently found embedded in structures built centuries or millennia later. The archaeologist Philip A. Barker gives the example of a late Roman period tombstone from Wroxeter that could be seen to have been cut down and undergone weathering while it was in use as part of an exterior wall and, possibly as late as the 5th century, reinscribed for reuse as a tombstone.

The Palatine Chapel is the royal chapel of the Norman Palace in Palermo, Sicily. This building is a mixture of Byzantine, Norman and Fatimid architectural styles, showing the tricultural state of Sicily during the 12th century after Roger I and Robert Guiscard conquered the island.

Palermo Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Palermo, located in Palermo, Sicily, southern Italy. It is dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. As an architectural complex, it is characterized by the presence of different styles, due to a long history of additions, alterations and restorations, the last of which occurred in the 18th century.

The Church of St. Mary of the Admiral, also called Martorana, is the seat of the Parish of San Nicolò dei Greci, overlooking the Piazza Bellini, next to the Norman church of San Cataldo and facing the Baroque church of Santa Caterina, in Palermo, Italy.

The Cathedral of Cefalù is a Roman Catholic basilica in Cefalù, Sicily. It is one of nine structures included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale.

A cross-in-square or crossed-dome plan was the dominant architectural form of middle- and late-period Byzantine churches. It featured a square centre with an internal structure shaped like a cross, topped by a dome.

The Symmachi–Nicomachi diptych is a book-size Late Antique ivory diptych dating to the late fourth or early fifth century, whose panels depict scenes of ritual pagan religious practices. Both its style and its content reflect a short-lived revival of traditional Roman religion and Classicism at a time when the Roman world was turning towards Christianity and rejecting the Classical tradition.

The Monza ampullae form the largest collection of a specific type of Early Medieval pilgrimage ampullae or small flasks designed to hold holy oil from pilgrimage sites in the Holy Land related to the life of Jesus. They were made in Palestine, probably in the fifth to early seventh centuries, and have been in the Treasury of Monza Cathedral north of Milan in Italy since they were donated by Theodelinda, queen of the Lombards,. Since the great majority of surviving examples of such flasks are those in the Monza group, the term may be used to cover this type of object in general.

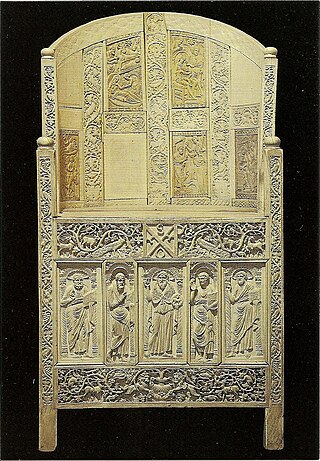

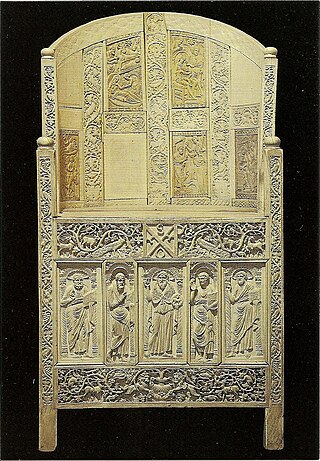

The Throne of Maximian is a cathedra that was made for Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna and is now on display at the Archiepiscopal Museum, Ravenna. It is generally agreed that the throne was carved in the Greek East of the Byzantine Empire and shipped to Ravenna, but there has long been scholarly debate over whether it was made in Constantinople or Alexandria.

Doula Mouriki was a Greek Byzantinologist and art historian. She made important contributions to the study of Byzantine art in Greece.

The Worcester Hunt Mosaic is a large Byzantine floor mosaic located at Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. The mosaic was originally constructed for an upscale villa in Daphne, just outside of Antioch. The mosaic was discovered during an archeological expedition which lasted between 1932 and 1939. It is currently the largest Antioch mosaic located within the United States. It measures approximately 20.5 feet x 23.3 feet.

Slobodan Ćurčić was an American art historian and Byzantinist.

Kainourgion, was a palantine hall built by Emperor Basil I from 867-886. Covered in mosaics to glorify the Macedonian dynasty, the Kainourgion depicted Basil's military victories and functioned as an imperial palace with audience chamber, a dining room, and connected bedrooms.