Related Research Articles

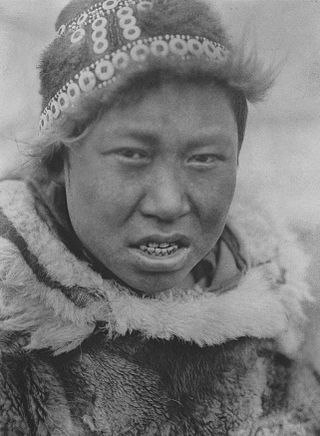

Eskimo is an exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit and the Yupik of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the Aleut, who inhabit the Aleutian Islands, are generally excluded from the definition of Eskimo. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the Eskaleut language family.

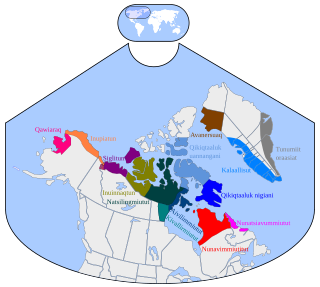

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and the adjacent subarctic regions as far south as Labrador. The Inuit languages are one of the two branches of the Eskimoan language family, the other being the Yupik languages, which are spoken in Alaska and the Russian Far East. Most Inuit people live in one of three countries: Greenland, a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark; Canada, specifically in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories, the Nunavik region of Quebec, and the Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut regions of Labrador; and the United States, specifically in northern and western Alaska.

The idea of linguistic relativity, also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, the Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism, is a principle suggesting that the structure of a language influences its speakers' worldview or cognition, and thus individuals' languages determine or shape their perceptions of the world.

The Yupik are a group of Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yupik peoples include the following:

The Eskaleut, Eskimo–Aleut or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan languages are a language family native to the northern portions of the North American continent, and a small part of northeastern Asia. Languages in the family are indigenous to parts of what are now the United States (Alaska); Canada including Nunavut, Northwest Territories, northern Quebec (Nunavik), and northern Labrador (Nunatsiavut); Greenland; and the Russian Far East. The language family is also known as Eskaleutian, Eskaleutic or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan.

Siberian Yupiks, or Yuits, are a Yupik people who reside along the coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in the far northeast of the Russian Federation and on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska. They speak Central Siberian Yupik, a Yupik language of the Eskimo–Aleut family of languages.

Sirenik Yupik, Sireniki Yupik, Sirenik, or Sirenikskiy is an extinct Eskimo–Aleut language. It was spoken in and around the village of Sireniki (Сиреники) in Chukotka Peninsula, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. The language shift has been a long process, ending in total language death. In January 1997, the last native speaker of the language, a woman named Vyjye, died. Ever since that point, the language has been extinct; nowadays, all Sirenik Eskimos speak Siberian Yupik or Russian.

Inuktitut, also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec, to some extent in northeastern Manitoba as well as the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. It is one of the aboriginal languages written with Canadian Aboriginal syllabics.

Central Siberian Yupik, is an endangered Yupik language spoken by the Indigenous Siberian Yupik people along the coast of Chukotka in the Russian Far East and in the villages of Savoonga and Gambell on St. Lawrence Island. The language is part of the Eskimo-Aleut language family.

The Yupik languages are a family of languages spoken by the Yupik peoples of western and south-central Alaska and Chukotka. The Yupik languages differ enough from one another that they are not mutually intelligible, although speakers of one of the languages may understand the general idea of a conversation of speakers of another of the languages. One of them, Sirenik, has been extinct since 1997.

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq, also known as Iñupiat, Inupiat, Iñupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is an Inuit language, or perhaps group of languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, as well as a small adjacent part of the Northwest Territories of Canada. The Iñupiat language is a member of the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan language family, and is closely related and, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible with other Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers. Iñupiaq is considered to be a threatened language, with most speakers at or above the age of 40. Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska, along with several other indigenous languages.

A snowclone is a cliché and phrasal template that can be used and recognized in multiple variants. The term was coined as a neologism in 2004, derived from journalistic clichés that referred to the number of Inuit words for snow.

Traditional Alaskan Native religion involves mediation between people and spirits, souls, and other immortal beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Northwest Coastal Indian cultures, but today are less common. They were already in decline among many groups when the first major ethnological research was done. For example, at the end of the 19th century, Sagdloq, the last medicine man among what were then called in English, "Polar Eskimos", died; he was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea, and was also known for using ventriloquism and sleight-of-hand.

Cultural emphasis is an important aspect of a culture which is often reflected though language and, more specifically, vocabulary. This means that the vocabulary people use in a culture indicates what is important to that group of people. If there are many words to describe a certain topic in a specific culture, then there is a good chance that that topic is considered important to that culture.

Sirenik or Sireniki are former speakers of a divergent Eskimo language in Siberia, before its extinction. The total language death of this language means that now the cultural identity of Sirenik Eskimos is maintained through other aspects: slight dialectal difference in the adopted Siberian Yupik language; sense of place, including appreciation of the antiquity of their settlement Sirenik.

Inuit are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon (traditionally), Alaska, and Chukotsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut languages, also known as Inuit-Yupik-Unangan, and also as Eskaleut. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

Proto-Eskimoan, Proto-Eskimo, or Proto-Inuit-Yupik, is the reconstructed ancestor of the Eskimo languages. It was spoken by the ancestors of the Yupik and Inuit peoples. It is linguistically related to the Aleut language, and both descend from the Proto-Eskaleut language.

Classifications of snow describe and categorize the attributes of snow-generating weather events, including the individual crystals both in the air and on the ground, and the deposited snow pack as it changes over time. Snow can be classified by describing the weather event that is producing it, the shape of its ice crystals or flakes, how it collects on the ground, and thereafter how it changes form and composition. Depending on the status of the snow in the air or on the ground, a different classification applies.

Chevak Cupʼik or just Cupʼik is a subdialect of the Hooper Bay–Chevak dialect of Yupʼik spoken in southwestern Alaska in the Chevak by Chevak Cupʼik Eskimos. Speakers of the Chevak subdialect refer to themselves as Cupʼik, while speakers of the Hooper Bay subdialect refer to themselves as Yupʼik, as in the Yukon-Kuskokwim dialect.

Naukan is a deserted Yupik village on Cape Dezhnev, Russia. Prior to 1958, it was the easternmost settlement in the Eurasian continent. This distinction is now held by the Russian village Uelen in the Chukotsky District.

References

- ↑ Pinker, Steven (1994). The Language Instinct. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 54-55

- 1 2 Krupnik, Igor; Müller-Wille, Ludger (2010), Krupnik, Igor; Aporta, Claudio; Gearheard, Shari; Laidler, Gita J. (eds.), "Franz Boas and Inuktitut Terminology for Ice and Snow: From the Emergence of the Field to the "Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax"", SIKU: Knowing Our Ice, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 377–400, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8587-0_16, ISBN 978-90-481-8586-3 , retrieved 2023-01-16

- 1 2 David Robson, New Scientist 2896, December 18 2012, Are there really 50 Eskimo words for snow?, "Yet Igor Krupnik, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center in Washington DC believes that Boas was careful to include only words representing meaningful distinctions. Taking the same care with their own work, Krupnik and others have now charted the vocabulary of about 10 Inuit and Yupik dialects and conclude that there are indeed many more words for snow than in English (SIKU: Knowing Our Ice, 2010). Central Siberian Yupik has 40 such terms, whereas the Inuit dialect spoken in Nunavik, Quebec, has at least 53, including matsaaruti, wet snow that can be used to ice a sleigh's runners, and pukak, for the crystalline powder snow that looks like salt. For many of these dialects, the vocabulary associated with sea ice is even richer."

- 1 2 3 Geoffrey K. Pullum's explanation in Language Log: The list of snow-referring roots to stick [suffixes] on isn't that long [in the Eskimoan language group]: qani- for a snowflake, apu- for snow considered as stuff lying on the ground and covering things up, a root meaning "slush", a root meaning "blizzard", a root meaning "drift", and a few others -- very roughly the same number of roots as in English. Nonetheless, the number of distinct words you can derive from them is not 50, or 150, or 1500, or a million, but simply unbounded. Only stamina sets a limit.

- ↑ Panko, Ben (2016). "Does the Linguistic Theory at the Center of the Film ‘Arrival’ Have Any Merit?". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ "Bad science reporting again: the Eskimos are back". Language Log. 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ↑ Cichocki, Piotr; Kilarski, Marcin (2010-11-16). "On "Eskimo Words for Snow": The life cycle of a linguistic misconception". Historiographia Linguistica. 37 (3): 341–377. doi:10.1075/hl.37.3.03cic. ISSN 0302-5160.

- ↑ The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax Archived 2018-12-03 at the Wayback Machine , Geoffrey Pullum, Chapter 19, p. 159-171 of The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language, Geoffrey K. Pullum, With a Foreword by James D. McCawley. 246 p., 1 figure, 2 tables, Spring 1991, LC: 90011286, ISBN 978-0-226-68534-2

- ↑ Robson, David (2013-01-14). "There really are 50 Eskimo words for 'snow'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2019-12-31.

- ↑ Ole Henrik Magga, Diversity in Saami terminology for reindeer, snow, and ice, International Social Science Journal Volume 58, Issue 187, pages 25–34, March 2006.

- ↑ Nils Jernsletten,- "Sami Traditional Terminology: Professional Terms Concerning Salmon, Reindeer and Snow", Sami Culture in a New Era: The Norwegian Sami Experience. Harald Gaski ed. Karasjok: Davvi Girji, 1997.

- ↑ Yngve Ryd. Snö--en renskötare berättar. Stockholm: Ordfront, 2001.

- ↑ "Martin, Laura. 1986. "Eskimo Words for Snow": A Case Study in the Genesis and Decay of an Anthropological Example. American Anthropologist, 88(2):418" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- ↑ Boas, Franz. 1911. Handbook of American Indian languages pp. 25-26. Boas "utilized" this part also in his book The Mind of Primitive Man . 1911. pp. 145-146.

- ↑ Some of them are borrowed from other languages, like firn (German), névé (French), penitentes (Spanish) and sastrugi (Russian).

- ↑ Whorf, Benjamin Lee. 1949. "Science and Linguistics" Reprinted in Carroll 1956.

- ↑ "There's Snow Synonym". The New York Times. February 9, 1984. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ Fortescue, Michael D.; Jacobson, Steven; Kaplan, Lawrence, eds. (2010). "PE qaniɣ 'falling snow'". Comparative Eskimo Dictionary: With Aleut Cognates (2nd ed.). Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-555-00-109-4.

- ↑ Fortescue, Michael D.; Jacobson, Steven; Kaplan, Lawrence, eds. (2010). "PE aniɣu 'snow (fallen)'". Comparative Eskimo Dictionary: With Aleut Cognates (2nd ed.). Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-555-00-109-4.

- ↑ Fortescue, Michael D.; Jacobson, Steven; Kaplan, Lawrence, eds. (2010). "PE apun 'snow (on ground)'". Comparative Eskimo Dictionary: With Aleut Cognates (2nd ed.). Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-555-00-109-4.

- ↑ Kaplan, Larry (June 2003). "Inuit Snow Terms: How Many and What Does It Mean? | Alaska Native Language Center". www.uaf.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-10.