Ottoman Albania refers to a period in Albanian history from the Ottoman conquest in the late 15th century to the Albanian declaration of Independence and official secession from the Ottoman Empire in 1912. The Ottomans first entered Albania in 1385 upon the invitation of the Albanian noble Karl Thopia to suppress the forces of the noble Balša II during the battle of Savra. They had some previous influence in some Albanian regions after the battle of Savra in 1385 but not direct control. The Ottomans placed garrisons throughout southern Albania by 1420s and established formal jurisdiction in central Albania by 1431. Even though The Ottomans claimed rule of all Albanian lands, most Albanian ethnic territories were still governed by medieval Albanian nobility who were free of Ottoman rule. The Sanjak of Albania was established in 1420 or 1430 controlling mostly central Albania, while Ottoman rule became more consolidated in 1481, after the fall of Shkodra and League of Lezhe with the country being mostly free in the period of 1443–1481. Albanians revolted again in 1481 but the Ottomans finally controlled Albania by 1488.

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha was an Ottoman statesman of Serbian origin most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in Ottoman Herzegovina into an Orthodox Christian family, Mehmed was recruited as a young boy as part of so called "blood tax" to serve as a janissary to the Ottoman devşirme system of recruiting Christian boys to be raised as officers or administrators for the state. He rose through the ranks of the Ottoman imperial system, eventually holding positions as commander of the imperial guard (1543–1546), High Admiral of the Fleet (1546–1551), Governor-General of Rumelia (1551–1555), Third Vizier (1555–1561), Second Vizier (1561–1565), and as Grand Vizier under three sultans: Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, and Murad III. He was assassinated in 1579, ending his near 15-years of service to several Sultans, as sole legal representative in the administration of state affairs.

Alemdar Mustafa Pasha was an Ottoman military commander and grand vizier.

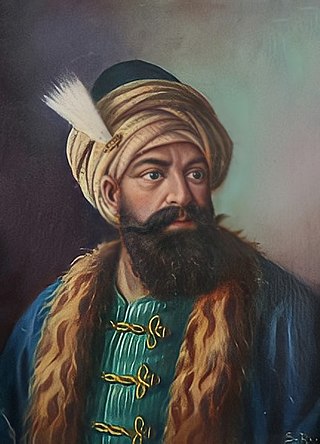

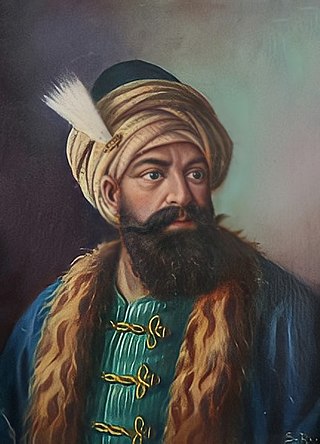

Kara Mahmud Bushati was an Albanian military commander who served as the governor of the Pashalik of Scutari, an Albanian pashalik, from 1775 until his death in 1796. A member of the Bushati family, Kara Mahmud was considered a descendent of Skanderbeg Crnojević.

Ibrahim Bushati or Ibrahim Bushat Pasha was a noble of the Bushati family in Ottoman controlled Albania near the city of Shkodër. Brother of Kara Mahmud Bushati, the Ottoman appointed governor of Shkodër, Albania. During his rule in Shkodra, Ibrahim was appointed Beylebey of Rumelia in 1805 and took part in the attempt to crush the First Serbian Uprising under Karađorđe Petrović after the Battle of Ivankovac. Ibrahim Bushati is also known to have aided Ali Pasha on various occasions. In fact Ali Pasha's two sons Muktar Pasha and Veil Pasha are known to have served under the command of Ibrahim Bushati in 1806.

Mustafa Pasha Bushatli, called Ishkodrali, was a semi-independent Albanian Ottoman statesman, the last hereditary governor of the Pashalik of Scutari. In 1810 he succeeded Ibrahim Bushati and ruled Shkodër until 1831.

The Bushati family is an Albanian Muslim family that ruled the Pashalik of Scutari from 1757 to 1831.

The Pashalik of Scutari (1757–1831), also known as the Bushati Pashalik, was an Albanian pashalik ruled by the Bushati family. Its capital was Shkodër and ruled areas in modern-day Albania and large majority of modern-day Montenegro.

Mehmed Bushati was the governor of the Pashalik of Scutari and founder of the Bushatli dynasty of Shkodër

The Albanian Pashaliks were three semi-independent pashaliks ruled by Albanian pashas from 1760 to 1831 and covering the territory of modern Albania, Kosovo, most of Montenegro, southern Serbia, western North Macedonia and most of mainland Greece. The degree of independence of these pashaliks varied over time, from semi-autonomous to de facto independent.

The First Ottoman–Venetian War was fought between the Republic of Venice with its allies and the Ottoman Empire from 1463 to 1479. Fought shortly after the capture of Constantinople and the remnants of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans, it resulted in the loss of several Venetian holdings in Albania and Greece, most importantly the island of Negroponte (Euboea), which had been a Venetian protectorate for centuries. The war also saw the rapid expansion of the Ottoman navy, which became able to challenge the Venetians and the Knights Hospitaller for supremacy in the Aegean Sea. In the closing years of the war, however, the Republic managed to recoup its losses by the de facto acquisition of the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus.

The siege of Shkodra took place from May 1478 to April 1479 as a confrontation between the Ottoman Empire and the Venetians together with the League of Lezhe and other Albanians at Shkodra and its Rozafa Castle during the First Ottoman-Venetian War (1463–1479). Ottoman historian Franz Babinger called the siege "one of the most remarkable episodes in the struggle between the West and the Crescent". A small force of approximately 1,600 Albanian and Italian men and a much smaller number of women faced a massive Ottoman force containing artillery cast on site and an army reported to have been as many as 350,000 in number. The campaign was so important to Mehmed the Conqueror that he came personally to ensure triumph. After nineteen days of bombarding the castle walls, the Ottomans launched five successive general attacks which all ended in victory for the besieged. With dwindling resources, Mehmed attacked and defeated the smaller surrounding fortresses of Žabljak Crnojevića, Drisht, and Lezha, left a siege force to starve Shkodra into surrender, and returned to Constantinople. On January 25, 1479, Venice and Constantinople signed a peace agreement that among other concessions ceded Shkodra to the Ottoman Empire. The defenders of the citadel emigrated to Venice, whereas many Albanians from the region retreated into the mountains. Shkodra then became a seat of the newly established Ottoman sanjak, the Sanjak of Scutari. The Ottomans held the city until Montenegro captured it in April 1913, after a six-month siege.

Battle of Martinići was the battle between Montenegro and Pashalik of Scutari which took place on the outskirts of the village Martinići, near Spuž, Montenegro.

The Çapanoğlu dynasty, also Cebbarzâdeler, Çaparzâdeler and Çaparoğulları, is Turkish dynasty that originates in the 17th-century Ottoman Empire and was once one of the most prominent Ottoman families. They became one of the most powerful dynasties in the empire in the 18th century.

The Sanjak of Durrës was one of the sanjaks of the Ottoman Empire. It was named for its capital Durrës and was also known as the Sanjak of Durazzo from its capital's Italian name. The sanjak was composed of the kazas of Durrës, Tirana, Shijak, Kavajë, and Krujë. The Sanjak of Durrës formed the southern half of the Vilayet of Scutari. The northern half was the Sanjak of Scutari. Durrës Sanjak also bordered the sanjaks of Manastir and Dibra to its northeast and the sanjak of Elbasan to the east and south. Its western border was the Adriatic Sea. Its terrain is generally flat and plain. Only the eastern parts of the kazas of Tirana and Kavajë were mountainous.

The First Scutari-Berat War was a military conflict between the Pashalik of Scutari under Mehmed Pasha Bushati against the Pashalik of Berat under Ahmet Kurt Pasha, who fought over the Sanjak of Durrës in 1775.

The Scuatri invasion of Montenegro, was a military campaign launched by Kara Mahmud Pasha, the head of the Pashalik of Scutari, against the Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro, as well as the Montenegrin tribes of Old Montenegro, Paštrovići and Brda. The campaign also included the capture of Spuž, a castle which was administered by the Bosnian Pasha, Ibrahim Pasha of Spuž.

The Battle of Kosovo in 1831 took place between The Vizier of Bosnia Husein-kapetan Gradaščević and his loyalists against the Ottoman Empire, whose troops were commanded by the Grand Vizier Reşid Mehmed Pasha.

The Second Scutari-Berat War was a military invasion launched by Mustafa Pasha of the Pashalik of Scutari against the Pashalik of Berat under Ahmet Kurt Pasha.

In mid-1805, during the Serbian Revolution, a conflict broke out within modern-day Montenegro. The Serb tribes of Kuči and Piperi from Brda, along with the Albanian tribe of Kelmendi from Malësia, took up arms against the Pashalik of Scutari and its ruler, Ibrahim Pasha of the Bushati family.