The Taos art colony was an art colony founded in Taos, New Mexico, by artists attracted by the culture of the Taos Pueblo and northern New Mexico. The history of Hispanic craftsmanship in furniture, tin work, and other mediums also played a role in creating a multicultural tradition of art in the area.

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe was an American modernist artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O'Keeffe has been called the "Mother of American modernism".

Alfred Stieglitz was an American photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his 50-year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz was known for the New York art galleries that he ran in the early part of the 20th century, where he introduced many avant-garde European artists to the U.S. He was married to painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

Barbara Buhler Lynes is an art historian, curator, professor, and preeminent scholar on the art and life of Georgia O'Keeffe. She retired on February 14, 2020 from her position as the Sunny Kaufman Senior Curator at the NSU Museum of Art in Fort Lauderdale, Florida to continue her scholarly work on O'Keeffe and American modernism. From 1999-2012, she served as the founding curator of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she curated or oversaw more than thirty exhibitions of works by O’Keeffe and her contemporaries. Lynes was also the Founding Emily Fisher Landau Director of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Research Center from 2001-2012. Prior to her work at the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Lynes served as an independent consultant to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. from 1992-1999 and has taught art history at Vanderbilt University, Dartmouth College, Montgomery College, and the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA).

The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum is dedicated to the artistic legacy of Georgia O'Keeffe, her life, American modernism, and public engagement. It opened on July 17, 1997, eleven years after the artist's death. It comprises multiple sites in two locations: Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Abiquiu, New Mexico. In addition to the founding Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, the O'Keeffe includes: the Library and Archive within its research center at the historic A.M. Bergere house; the Education Annex for youth and public programming; Georgia O'Keeffe's historic Abiquiu Home and Studio; the O'Keeffe Welcome Center in Abiquiu; and Museum Stores in both Santa Fe and Abiquiu. Georgia O'Keeffe's additional home at the Ghost Ranch property is also part of the O'Keeffe Museum's assets, but is not open to the public.

Georgia O'Keeffe is a 2009 American television biographical drama film, produced by City Entertainment in association with Sony Television, about noted American painter Georgia O'Keeffe and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The film was directed by Bob Balaban, executive-produced by Joshua D. Maurer, Alixandre Witlin and Joan Allen, and line-produced by Tony Mark. Shown on Lifetime Television, it starred Joan Allen and Jeremy Irons in lead roles.

Blue and Green Music is a 1919–1921 painting by the American painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

Katharine Nash Rhoades was an American painter, poet and illustrator born in New York City. She was also a feminist.

Marion Hasbrouck Beckett was an American painter.

Rebecca Salsbury James (1891–1968) was a self-taught American painter, born in London, England of American parents who were traveling with the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show. She settled in New York City, where she married photographer Paul Strand. Following her divorce from Strand, James moved to Taos, New Mexico where she fell in with a group that included Mabel Dodge Luhan, Dorothy Brett, and Frieda Lawrence. In 1937 she married William James, a businessman from Denver, Colorado who was then operating the Kit Carson Trading Company in Taos. She remained in Taos until her death in 1968.

Oriental Poppies, also called Red Poppies, made by Georgia O'Keeffe in 1927, is a close-up of two papaver orientale that fills the entire canvas.

Georgia O'Keeffe made a number of Red Canna paintings of the canna lily plant, first in watercolor, such as a red canna flower bouquet painted in 1915, but primarily abstract paintings of close-up images in oil. O'Keeffe said that she made the paintings to reflect the way she herself saw flowers, although others have called her depictions erotic, and compared them to female genitalia. O'Keeffe said they had misconstrued her intentions for doing her flower paintings: "Well – I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don't."

Light Coming on the Plains is the name of three watercolor paintings made by Georgia O'Keeffe in 1917. They were made when O'Keeffe was teaching at West Texas State Normal College in Canyon, Texas. They reflect the evolution of her work towards pure abstraction, and an early American modernist landscape. It was unique for its time. Compared to Sunrise that she painted one year earlier, it was simpler and more abstract.

The Flag is a painting by Georgia O'Keeffe (1918), that represents her anxiety about her brother being sent to fight in Europe during World War I, a war that was particularly controversial and dangerous due to its use of new modern weapons and tactics, like the machine gun, mustard gas, naval mines and torpedoes, high-powered artillery guns, and combat aircraft. Due to government restrictions on the freedom of speech included in the Espionage Act of 1917 the painting was not displayed until 1968. It is in the collection of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

The early works of American artist Georgia O'Keeffe are those made before she was introduced to the principles of Arthur Wesley Dow in 1912.

Black Iris, sometimes called Black Iris III, is a 1926 oil painting by Georgia O'Keeffe. Art historian Linda Nochlin interpreted Black Iris as a morphological metaphor for female genitalia. O'Keeffe rejected such interpretations in a 1939 text accompanying an exhibition of her work by writing: "Well—I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don't." She attempted to do away with sexualized readings of her work by adding a lot of detail.

My Shanty, Lake George is a 1922 painting by Georgia O'Keeffe. From 1918 to 1934, Georgia O'Keeffe spent part of the year at Alfred Stieglitz's family estate in Lake George. The depicted shanty was O'Keeffe's studio, which was painted in subdued tones in response to criticism from Stieglitz' circle—Arthur Dove, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and Paul Strand. O'Keeffe said of the painting: "The clean, clear colors were in my head, but one day as I looked at the brown burned wood of the Shanty I thought, "I can paint one of those dismal-colored paintings like the men. I think just for fun I will try—all low-toned and dreary with the tree beside the door." My Shanty was the first painting by O'Keeffe purchased by Duncan Phillips.

Georgia O'Keeffe created a series of paintings of skyscrapers in New York City between 1925 and 1929. They were made after O'Keeffe moved with her new husband into an apartment on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel, which gave her expansive views of all but the west side of the city. She expressed her appreciation of the city's early skyscrapers that were built by the end of the 1920s. One of her most notable works, which demonstrates her skill at depicting the buildings in the Precisionist style, is the Radiator Building—Night, New York, of the American Radiator Building.

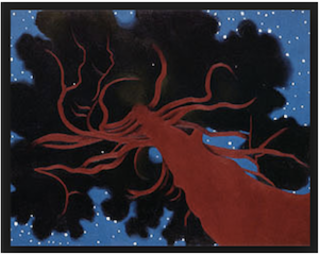

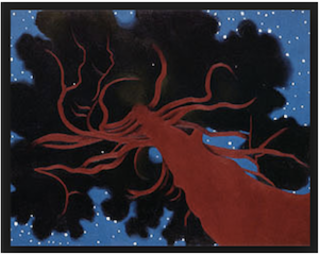

The Lawrence Tree is a painting by Georgia O'Keeffe in 1929 of a large ponderosa pine tree on the D. H. Lawrence Ranch in Taos County, New Mexico. The tree still survives, and may be visited at the Lawrence Ranch.

Georgia E. Engelhard Cromwell was an American mountaineer in the Canadian Rockies and the Selkirk and Purcell ranges. She was the first female climber to ascend many of the peaks in the Rockies and was the leading female amateur climber of her day. She was also an accomplished painter and photographer.