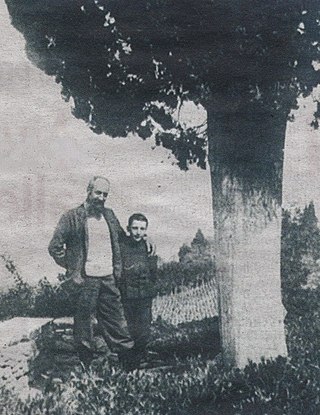

Francesco Ruffini (Lessolo, April 10, 1863 - Turin, March 29, 1934) was an Italian jurist, historian, politician and antifascist.

Francesco Ruffini (Lessolo, April 10, 1863 - Turin, March 29, 1934) was an Italian jurist, historian, politician and antifascist.

Francesco Ruffini attended the Liceo Classico Carlo Botta in Ivrea. After teaching in Pavia and Genoa, he became a professor in Turin, first of History of Law, then of Ecclesiastical Law. Among his students there were Arturo Carlo Jemolo , Alessandro Galante Garrone , Piero Gobetti (who was also his editor), and Mario Falco . He was dean of the University of Turin from 1910 to 1913. [1]

He was appointed Senator of the Kingdom of Italy in 1914. A member of numerous academic bodies, including the Academia dei Lincei and the Istituto Lombardo Accademia di Scienze e Lettere, he was president of the Accademia delle Scienze di Torino from 1922 to 1928. [1] [2]

In 1925, he was among the signatories of the Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, drafted by Benedetto Croce, who in 1927 dedicated to him the book Uomini e cose della vecchia Italia . [3] In 1928 Ruffini was attacked by a group of fascists inside the University of Turin, where he was teaching. Several students took his defense, including Alessandro Galante Garrone and Dante Livio Bianco. [1]

A staunch secularist, together with Benedetto Croce and Alberto Bergamini he openly criticized the Lateran Treaty, voting against its ratification: in the parliamentary session of May 24, 1929, Croce had attacked the hypothesis of creating the Concordat between Church and State. [1]

Together with his son, Edoardo Ruffini Avondo , in 1931 he was among the few professors who gave up their professorships in order not to take the oath of allegiance to fascism. [4] He died three years later in Turin. [1]

Parco Ruffini in Turin, a statue placed in the portico of the University of Turin Dean's Office, and the third floor of the Luigi Einaudi Campus library containing the University of Turin's collection of legal volumes, were dedicated to his memory after the war. [5]

Judged “a master of freedom” who was always interested in the relationship between state and church, [6] Ruffini studied the figure of Cavour, of whom he was a great admirer. [7]

In 1901, his analysis on the historical origins of the idea of religious freedom resulted in the writing of the work Religious Liberty. [8] The following year, he edited the handbook Storia del diritto privato italiano, written by his professor Cesare Nani and published posthumously. [1]

Also significant is his writing The ‘Cabale Italique’ in seventeenth-century Geneva, in which Ruffini makes a brief analysis of the Italian lineage that emigrated and settled in Switzerland, and in particular in Geneva, following the Protestant Reform; among other things, there are extensive references to the history of Italy, with a closer look at Tuscany, in particular the city of Lucca. [1]

The entire collection of his works has been digitized by the Norberto Bobbio Library. It was archived on May 26, 2020, in the Internet Archive and is freely available in the public domain. [9]

Benedetto Croce, OCI, COSML was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A political liberal in most regards, he formulated a distinction between liberalism and "liberism". Croce had considerable influence on other Italian intellectuals, from Marxists to Italian fascists, such as Antonio Gramsci and Giovanni Gentile, respectively.

Alfredo Oriani was an Italian author, writer and social critic. He is often considered a precursor of Fascism, and in 1940 his books were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum of the Catholic Church.

Luigi Numa Lorenzo Einaudi was an Italian politician and economist who served as President of Italy from 1948 to 1955 and is considered one of the founding fathers of the Italian Republic.

Marco Minghetti was an Italian economist and statesman.

Carlo Levi was an Italian painter, writer, activist, independent leftist politician, and doctor.

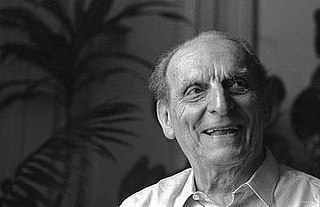

Norberto Bobbio was an Italian philosopher of law and political sciences and a historian of political thought. He also wrote regularly for the Turin-based daily La Stampa. Bobbio was a social liberal in the tradition of Piero Gobetti, Carlo Rosselli, Guido Calogero, and Aldo Capitini. He was also strongly influenced by Hans Kelsen and Vilfredo Pareto. He was considered one of the greatest Italian intellectuals of the 20th century.

Francesco de Sanctis was an Italian literary critic, scholar and politician, leading critic and historian of Italian language and literature during the 19th century.

Piero Gobetti was an Italian journalist, intellectual, and anti-fascist. A radical and revolutionary liberal, he was an exceptionally active campaigner and critic in the crisis years in Italy after the First World War and into the early years of Fascist Italy.

Carlo Alberto Rosselli was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, non-Marxist socialism inspired by the British labour movement that he described as "liberal socialism". Rosselli founded the anti-fascist militant movement Giustizia e Libertà. Rosselli personally took part in combat in the Spanish Civil War, where he served on the Republican side.

Luigi Pareysón was an Italian philosopher, best known for challenging the positivist and idealist aesthetics of Benedetto Croce in his 1954 monograph, Estetica. Teoria della formatività, which builds on the hermeneutics of the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Carlo Francesco Gabba was an Italian jurist and professor at the University of Pisa who has received several awards and titles. His studies and legal constructions deeply influenced the law in several countries.

Silvio Spaventa was an Italian journalist, politician and statesman who played a leading role in the unification of Italy, and subsequently held important positions within the newly formed Italian state.

Pasquale Chessa, born in Alghero, is an Italian historian and journalist.

Gaetano Cozzi was an Italian historian, professor at Padua University, and researcher with the Giorgio Cini Foundation and Fondazione Benetton Studi e Ricerche. He was a specialist in Venetian history, with special attention to the institutions, the relationship between law and society and the cultural environment.

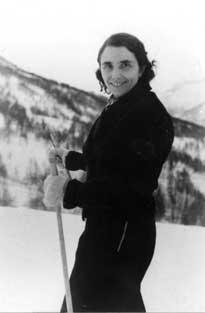

Ada Gobetti was an Italian teacher, journalist and anti-fascist leader.

Lellia Cracco Ruggini was an Italian historian of Late Antiquity and professor emerita of the University of Turin. Her particular interests were in economic and social history, the history of ideas, and modern and ancient historiography. She specialized in the period from the second to seventh centuries AD.

Massimo Mila was an Italian musicologist, music critic, intellectual and anti-fascist.

Luisa Monti Sturani was an Italian anti-fascist writer and teacher.

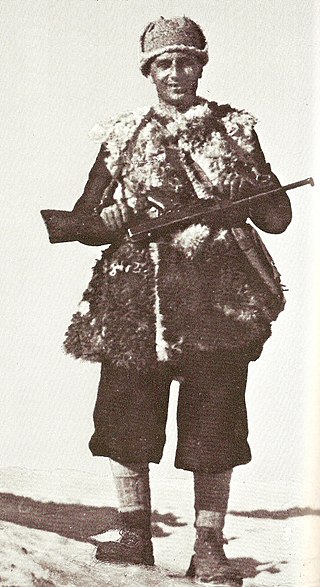

Dante Livio Bianco achieved early distinction among legal professionals as an exceptionally able Italian civil lawyer, and then came to wider prominence as a wartime partisan leader. He was awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valor twice. He survived the war but nevertheless died at a relatively young age due to a climbing accident.

Giacinto de' Sivo was an Italian politician, historian and journalist. De' Sivo was a leading legitimist historian after the fall of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and his books provided the main intellectual support in the struggle to undermine the legitimacy of the Kingdom of Italy.