Related Research Articles

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

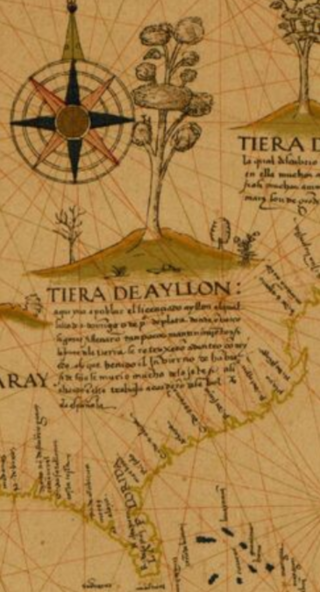

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United States. Ayllón's account of the region inspired a number of later attempts by the Spanish and French governments to colonize the southeastern United States.

The Waccamaw people were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, who lived in villages along the Waccamaw and Pee Dee rivers in North and South Carolina in the 18th century.

The Cape Fear Indians were a small, coastal tribe of Native Americans who lived on the Cape Fear River in North Carolina.

The Winyaw were a Native American tribe living near Winyah Bay, Black River, and the lower course of the Pee Dee River in South Carolina. The Winyaw people disappeared as a distinct entity after 1720 and are thought to have merged with the Waccamaw.

The Meherrin people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who spoke an Iroquian language. They lived between the Piedmont and coastal plains at the border of Virginia and North Carolina.

The Pedee people, also Pee Dee and Peedee, were a historic Native American tribe of the Southeastern United States. Historically, their population has been concentrated in the Piedmont of present-day South Carolina. It is believed that in the 17th and 18th centuries, English colonists named the Pee Dee River and the Pee Dee region of South Carolina for the tribe. Today four state-recognized tribes, one state-recognized group, and several unrecognized groups claim descent from the historic Pedee people. Presently none of these organizations are recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with the Catawba Indian Nation being the only federally recognized tribe within South Carolina.

Winyah Bay is a coastal estuary that is the confluence of the Waccamaw River, the Pee Dee River, the Black River, and the Sampit River in Georgetown County, in eastern South Carolina. Its name comes from the Winyaw, who inhabited the region during the eighteenth century. The historic port city of Georgetown is located on the bay, and the bay generally serves as the terminating point for the Grand Strand.

San Miguel de Gualdape was a short-lived Spanish colony founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón. It was established somewhere on the coast of present-day Carolinas or Georgia, but the exact location has been the subject of a long-running scholarly dispute. It was the first temporarily successful European settlement in what became the continental United States.

The Santee were a historic tribe of Native Americans that once lived in South Carolina within the counties of Clarendon and Orangeburg, along the Santee River. The Santee were a small tribe even during the early eighteenth century and were primarily centered in the area of the present-day town of Santee, South Carolina. Their settlement along the Santee River has since been dammed and is now called Lake Marion. The Santee Indian Organization, a state-recognized tribe within South Carolina claim descent from the historic Santee people but are not presently federally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Chicora was a legendary Native American kingdom or tribe sought during the 16th century by various European explorers in present-day South Carolina. The legend originated after Spanish slave traders captured an Indian they called Francisco de Chicora in 1521; afterward, they came to treat Francisco's home country as a land of abundant wealth and natural resources. The "Chicora Legend" influenced both the Spanish and the French in their attempts to colonize North America for the next 60 years.

The Waccamaw Siouan Indians are one of eight state-recognized tribes in North Carolina. Also known as the Waccamaw Siouan Indian Tribe, they are not federally recognized. They are headquartered in Bolton, North Carolina, in Columbus County, and also have members in Bladen County in southeastern North Carolina.

The Cheraw people, also known as the Saraw or Saura, were a Siouan-speaking tribe of Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, in the Piedmont area of North Carolina near the Sauratown Mountains, east of Pilot Mountain and north of the Yadkin River. They lived in villages near the Catawba River.

The Wateree were a Native American tribe in the interior of the present-day Carolinas. They probably belonged to the Siouan-Catawba language family. First encountered by the Spanish in 1567 in Western North Carolina, they migrated to the southeast and what developed as South Carolina by 1700, where English colonists noted them.

The Congaree were a historic Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands who once lived within what is now central South Carolina, along the Congaree River.

The Cusabo were a group of American Indian tribes who lived along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean in what is now South Carolina, approximately between present-day Charleston and south to the Savannah River, at the time of European colonization. English colonists often referred to them as one of the Settlement Indians of South Carolina, tribes who "settled" among the colonists.

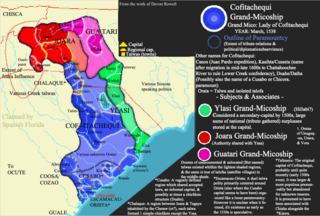

Cofitachequi was a paramount chiefdom founded about AD 1300 and encountered by the Hernando de Soto expedition in South Carolina in April 1540. Cofitachequi was later visited by Juan Pardo during his two expeditions (1566–1568) and by Henry Woodward in 1670. Cofitachequi ceased to exist as a political entity before 1701.

The Sissipahaw or Haw were a Native American tribe of North Carolina. Their settlements were generally located in the vicinity of modern-day Saxapahaw, North Carolina on the Haw River in Alamance County upstream from Cape Fear.

Woccon was one of two Catawban languages of what is now the Eastern United States. Together with the Western Siouan languages, they formed the Siouan language family. It is attested only in a vocabulary of 143 words, printed in a 1709 compilation by English colonist John Lawson of Carolina. The Woccon people that Lawson encountered have been considered by scholars to have been a late subdivision of the Waccamaw.

The Kiawah were a tribe of Cusabo people, an alliance of Indigenous groups in lowland regions of the coastal region of what became Charleston, South Carolina.

References

- ↑ Quattlebaum, Paul (1956). The Land Called Chicora (1st ed.). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. pp. 11–14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 First Descriptions of an Iroquoian People: Spaniards among the Tuscarora before 1522 (PDF), Coastal Carolina Indians Center, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08

- ↑ Jerald T. Milanich (14 August 1996). Timucua. VNR AG. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-55786-488-8.

- ↑ John Reed Swanton (1922). Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. Government Printing Office. pp. 32.

- ↑ Quattlebaum, Paul (1956). The Land Called Chicora (1st ed.). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ David J. Weber (14 May 2014). Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-300-15621-8.

- 1 2 Lawrence Sanders Rowland; Alexander Moore; George C. Rogers (1996). The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-57003-090-1.

- ↑ Paul E. Hoffman (15 December 2015). A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast During the Sixteenth Century. LSU Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8071-6474-7.

- ↑ Paul E. Hoffman (15 December 2015). A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast During the Sixteenth Century. LSU Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8071-6474-7.

- ↑ Peter O. Koch (13 March 2009). Imaginary Cities of Gold: The Spanish Quest for Treasure in North America. McFarland. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-7864-5310-8.

- ↑ Edward McCrady (1897). The History of South Carolina Under the Proprietary Government, 1670-1719. Vol. I. Heritage Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7884-4610-8.

- John R. Swanton, "Early History of the Creek Indians and their Neighbors", Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1922, pp. 32–48

- "First Descriptions of an Iroquoian People: Spaniards among the Tuscarora before 1522", Dr. Blair Rudes, Coastal Carolina Indians Center, 2004